Indifference

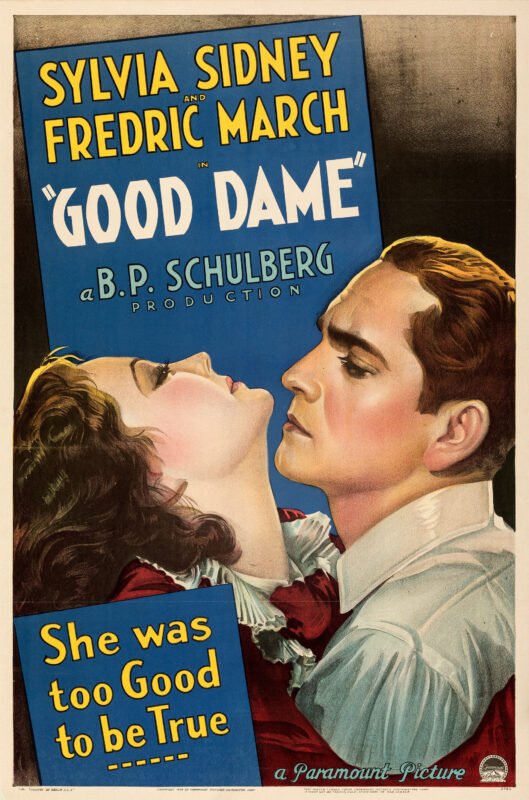

Starring: Sylvia Sidney, Fredric March, Jack La Rue, Noel Francis, Russell Hopton, Bradley Page, Kathleen Burke

Directed by: Marion Gering

Released by: Paramount Pictures

Run time: 74 minutes

Release date: March 17, 1934*

Availability

A Paramount release, this is currently owned by Universal Studios.

The film has not been released on DVD or blu-ray. It can be found via gray market sellers or on user-uploaded streaming services.

Currently it is available on YouTube.

(If the link is not present here, it has been taken down.)

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Innocent chorine Sylvia Sidney gets forced into the life of a carnival kootch dancer, albeit temporarily.

- Jack La Rue, in pretty typical Jack La Rue bit, attempts to sexually assault Sidney.

- Much of the film’s action is set around a hotel where Fredric March usually picks up women and spends the night in rooms other than his own.

- Sidney and March’s characters sleep together before getting married or even thinking that they may want to get married.

- The protagonists of this films are a flimflam man and his dame; ends with assault and robbery, but all is forgiven as the curtain closes down.

Good Dame: An Ongoing Dispute

“Come on baby, take ’em off!”

“Take what off?!”

“The wings!”

I don’t know quite how to categorize Good Dame, the kind of movie that feels like Warner Bros. dropped the script over at Paramount and someone accidentally made it.

That’s not to say the two studios were always diametrically opposed from one another– Warners did glamor just as Paramount did, while Paramount made conman Depression dramas as Warners did. But this one feels like a Warner Bros. script landed in their laps, not the least of which because Fredric March plays a fast-talking conman with the same quirks and intonations as Warner’s biggest star of the time, James Cagney.

Stars doing gags on their rivals was nothing new at the time (Garbo had aped Marlene Dietrich for As You Desire Me, and I’m avowed fan of Norma Shearer’s outright send-up of Garbo in 1939’s Idiot’s Delight), and for the record, Spencer Tracy was desperately trying to make the same Cagney-lite shtick work as a more ongoing prospect over at Fox. But Fredric March is not James Cagney, lacking that gift for patter in the same roundabout style. He also can’t quite master the necessary indifference his character must show towards Sylvia Sidney during much of the film; he likes women a little too much.

Now, you may ascertain that Cagney’s persona overtly horny as well. Who can forget the way he looked over Alice White in Picture Snatcher? Or the many passes he made at Blondell in Blonde Crazy? No, dear reader, while Cagney was certainly a virile man in many ways, that was a secondary aspect to his attitude and nature. His was a machismo unleashed, often representing a toxic masculinity unbound, especially in films like Hard to Handle and The Public Enemy. But while Cagney’s sexual desires and urges were driven by his own unbounded ego, Fredric March has a much more reserved, but no less carnivorous, appraisal of the fairer sex. His was that of bemused observer, sometimes troubled, but the type of leading man who could get the stars in his eyes look aflutter at the moment his heart beats faster; Cagney, simply, could never.

(In case you notice me delving more into background minutiae this review, it is because I have a feeling anyone out there who drops in on a review of Good Dame probably doesn’t need me to hand hold them on film history; this movie is an obscure one, currently sitting at a 100 ratings at IMDB and less than a half dozen reviews at Letterboxd. While this doesn’t make it the most obscure movie I’ve reviewed on this site by far, I also feel that if you’re watching it, it’s for one of three reasons: Sylvia Sidney completionism, Fredric March completionism, or you are attempting to watch every single pre-Code film ever made perhaps because of a decision you made more than a decade ago to start watching all pre-Code films knowing full and well you wouldn’t complete it until well-past retirement age.) (But I digress.)

Fredric March’s skills as a leading man and a romantic lead, especially in the pre-Code era, are directly tied to his own recalcitrance. He can love, he can hope, he can dream, but he is also always his own worst enemy. Whether he is Dr. Jekyll or Death itself, March’s best roles are those of a man who sees the poetry of life in a woman’s arms but screws it up seven ways to Sunday because he lacks the convictions to follow through. The triumph is when he overcomes them (sometimes; see Smilin’ Through) or the horror is when he doesn’t (often; see Hyde, Death, or especially his Jerry in the only other film he made with Sylvia Sidney, Merrily We Go to Hell).

This is all a long (very long) way to say that there is nothing in March’s persona that begins to emulate Cagney’s schtick, and putting him in a movie where he is playing a fast talking palooka would be the equivalent of making Bronx-born Sylvia Sidney play a Japanese geisha.

(See Madame Butterfly because of course I can’t make this up.)

This is why Good Dame doesn’t work. It’s a– wait. I haven’t done the plot description yet, have I? That’s probably useful at this point.

There is a carnival in town. Featured is card sharp Mace (March). When one of his three-card monty gags goes awry, his friend Spats (Russell Hopton) lifts a woman’s purse as a distraction, and she is, as you may have surmised, Lillie Taylor (Sidney). Lillie is an innocent chorus girl who is trying to make it back to her mom in Chicago, but, without the money in her purse, is recruited into the circus’ “kootch girl” show by a drooling Bluch Brown (Jack La Rue). During this hubbub, Mace tries to pick up Lillie, and she agrees to let him buy her dinner, neither of them realizing that he is doing so with her own stolen money.

Complications arise– a fancy movie reviewer way of saying a lot of baloney happens– and Mace and Lillie find themselves trapped in the small town without a penny to their names, living in adjoined rooms in a flop hotel. They mix like water and oil but have nowhere else to turn. To get out of town, Mace begins working as a door-to-door salesman with Lillie as the distraction. When one sale goes the wrong way, Mace and Lillie both look like they’ll face jail time unless they can finally admit, in front of the judge, what is going on between them and where it’s going to go next.

Where Warner Bros. movies in a case like this would simply up the wisecracks and violence and let the stars’ chemistry do their stuff as the film goes on, Paramount is a much talkier studio, and thus the second half of the film is filled with the two characters dancing around what love is, how they feel about love, and arguing simply for the sake of tossing out more lingo than any person could reasonably be expected to parse. Discovering this film isn’t based on a stage play, considering most of the film’s second half occupies two adjacent hotel rooms, was one of its few surprises.

The moral story at the center is a common one, in whether love in a time of desperation can exist between two people who don’t have the means to keep themselves away from the twin despondencies of leeches and lawmen. There are lot of pre-Codes that examine this, and, frankly, most of them do it much better.

What is a nice surprise for the film is Sylvia Sidney, the down and out of luck poster girl of the Great Depression, perhaps only competing with Helen Twelvetrees in the entire 1930s for having singularly terrible luck with men. With her sad eyes and emotive power, Sidney often spent most of her films jostled about, mostly between terrible beaus but other times simply running smack dab into unkind fate. Good Dame is a bit nicer to her than usual, even after Jack La Rue threatens her, she gets forced into kootch dancing, gets threatened with jail time, and has to cover up a bevy of crimes. Sidney is allowed to give her Lillie some spunk. The rat-a-tat dialogue that March can’t seem to find the over or under on, she hits as an easy bullseye.

Good Dame is a lot of bickering and some really convoluted hijinks, but Sidney is what helps to pave over the weaker parts. If you ever find yourself out and out thinking that a reasonable reason to watch any given movie is to see Sylvia Sidney smile, then (and only then) this one succeeds.

Image Gallery

Trivia, Miscellany & Links

- Kathleen Burke, who played the Panther Woman in Island of Lost Souls, appears briefly as a woman that Mace tries to chat up at the carnival. Also, the customer who calls the right card at the film’s beginning is future three-time Academy Award-winner Walter Brennan.

- Andre Sennwald in The New York Times absolutely body checks this movie, starting his review by calling it, “an average specimen of that type of bitter realism which the scenarists turn out after a careful study of the wood pulp fiction produced in New York by spectacled hacks. The improvement Hollywood has made recently in its technique for holding the mirror up to life is based upon its ability to avoid false, vulgar and unfunny stories like this one.” (New York Times).

- If that last line stands out to you, it’s because both the New York Times and Variety judge the film based on the contemporaneous blowback in 1934 against ‘immoral’ pictures. While Sennwald thinks its still too much, Variety, in a generally positive review, notes the movie is “soft pedaling on the cooch and flesh features.” (Variety)

- Both reviews, as well as Cliff Aliperti at Immortal Ephemera, come to pretty much the same conclusion: if you like Sylvia Sidney, you will enjoy this movie. Cliff adds, “Good Dame is a small movie with big stars offering a tiny slice of romance for the down and out. While it’s great to see the young lovers escape the carnival life, it’s a shame that the show couldn’t have at least stayed in town with them.” (Immortal Ephemera)

More to Explore

What is Pre-Code?

Click to learn more about pre-Code Hollywood, 1930-4, when movies were sexy, smart and sophisticated.

Index of Film Reviews

Browse all of the movie reviews on the site as well as schedules and pages that detail the world of pre-Code.

Explore the Pre-Code Era

Dig through the pre-Code era through its highlights, its biggest hits, its essential films, and more.

1 Comment

amycondit · February 4, 2022 at 11:47 am

Thank you, Danny! I’m a completist in all areas that you spoke of, & since this is a pre-code that’s new to me, I’ll be watching it tonight! I appreciate the detail in all your posts.

Comments are closed.