|

|

|

| Flo Helen Twelvetrees |

Babe Robert Armstrong |

McTeague Charles Bickford |

| Released by Fox Pathe | Directed by Ryan Murphy |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Drinking and speakeasies.

- Everyone is after Flo’s virtue. Or if they haven’t got it, they don’t believe she still has it.

- Not the nicest portrayal of South American natives.

- Someone ends up being shot dead and the only punishment is the one that weighs eternally on the killer’s soul.

Panama Flo: Quagmire’d

“One of these days, I’m gonna be king of South America. You can be queen.”

“You’re gonna get crowned right now if you don’t stop pawing me.”

I don’t know if I’ve ever seen an actress portray grief as palpably as Helen Twelvetrees does in Panama Flo. It doesn’t radiate so much as pull in. We can see that center of blackness in her as the world presents new and more horrific bouts of bad luck to the poor chorine. By the end of the film, that hole may just be all that’s left.

Flo is a showgirl in a Panama dance hall named Sadie’s. She has a sweet, innocent romance with an aviator named Babe. When her show is closed early with Sadie reneging on her promise to ship the girls back to their home of New York, Flo is in a jam. Babe is leaving for a few months and she refuses to take his money if a wedding ring doesn’t come along for the ride. So she’s stuck hanging around Sadie’s, without her love and without a dime. Sadie suggests she lightens the load of a drunk customer but unfortunately picks out the grizzly McTeague for Flo to try her charms on.

Up to this point, Panama Flo has had a pretty downbeat but unimpressive start– director Ryan Murphy has served up two fairly long montages for a 73 minute movie and Robert Armstrong’s makeup looks pancaked on. But the entrance of Charles Bickford as McTeague charts the film’s course towards something darker and more exciting. As he catches Helen in the act of slipping a few bills off his wad of cash, he flies into a rage, mercilessly throwing her around and dragging her through the dark foreboding streets while bellowing threats. Finding that the money she’d stolen has been ripped off by a fellow dancer, McTeague forces her to return with him to his home deep in the South American jungle. She agrees, so long as he promises “not to get rough.” It’s unlikely the promise will last long.

McTeague’s hut is isolated, cramped, lonely, and only brightened up by the pile of broken alcohol bottles out front that he regularly adds to. He kicks out the native girl who he’d kept around as ‘maid’ before Flo’s arrival, which sets off some ugly tensions at the local village. McTeague, whenever he isn’t drinking and raping, is a wildcatter by trade and fully believes he’s on the verge of discovering a massive South American oilfield. And, almost immediately, he goes back on his word to Flo– defeated, just once, by the fact that she managed to smuggle a gun into her bedroom to ward him off.

Babe arrives just in the nick of time, landing his plane under the guise of engine trouble and surreptitiously working with Flo to help her escape. But he’s also interested in those plans that McTeague has for the massive oil find. Will they get out under the drunkard’s nose– or is more tragedy in store for Flo?

Spoilers.

Flo finds that Babe has betrayed her– he’s far more interested in McTeague’s oil plotting than in saving her from the jungle hellhole. When she threatens him with a gun after he promises to leave her behind, he throws a chair at her and she fires. She wakes up later with McTeague returned and Babe dead, grief struck as a sympathetic McTeague arranges her passage out of there and helpfully hides the body and airplane of the man who she believes she killed.

The film ends on a note of ambiguity as we return to the present and McTeague reveals why he’s demanding Flo’s return to Panama. It’s not to force her to answer for the murder, but to finally come clean– Flo had been passed out when the murder occurred. While she’d winged Babe, it was actually McTeague who finished the job. He let her think she’d committed the murder in order to keep her quiet, but now, three years later, he’s going to make it up to her.

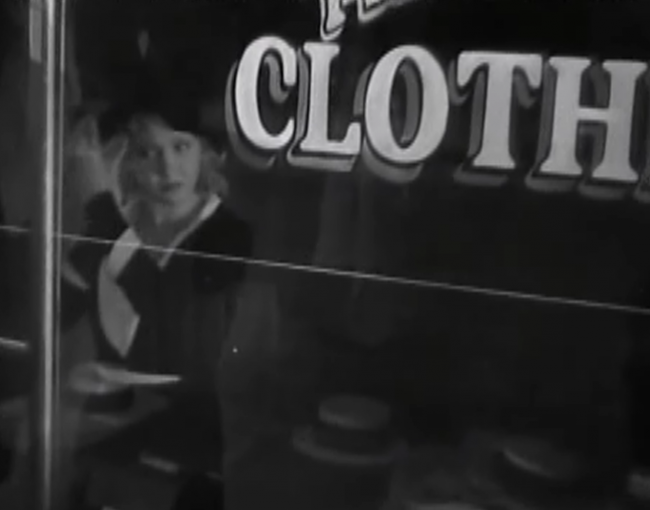

But how the hell do you make that up to someone? He can’t. The two part in a huff, her pretending to have found a rich man to make her happy and him pretending to be poor. She pauses in front of a menswear window, hastily wiping off the makeup smudges and trying to put herself back together, not just physically but mentally. For three years, she thought she was a murderess, a killer of a man who she’d loved. Now she was free. McTeague stole those years from her, in revenge for her refusal of intimacy and to give him the time to make his riches. He follows her feebly as she walks around the block. Though he’s in a limousine.

The more optimistic (and less demanding viewers) may see a romance in their future, but it’s hopeless. Where she goes, he may follow, but he can’t give her back what he’s stolen. Flo is and always be that reflection in the window, warped and distorted. And there is nothing she can do about it.

End spoilers.

Under Murphy’s direction, the film is full of energetic tracking shots and absolutely frightening action. McTeague’s drunken threats are laced with physical punctuation, and the roughhousing between him and Twelvetrees seems violent and shocking. While not as steamy as the Indochina jungles of Red Dust, the South American forest is still dripping with atmosphere, often half lit and feeling like the ends of the earth. It gives a physical depiction of the desperation as McTeague never leaves and that damned record player just keeps playing its one song.

The open ended finish is a great, prowling touch to the proceedings. Charles Bickford lacks the charm to make McTeague romantic at all, which makes the film feel all the more sinister and grimy. Robert Armstrong can be really bad in other movies, but he’s fine here, his leading man bravado nicely deflated by his more sinister leanings. And Helen Twelvetrees truly is the star of the show, giving Flo’s tragedy a wonderful immediacy.

Panama Flo is an interesting look down the rabbit hole for 1930s womanhood. You want love? Adventure? Romance? That stuff ain’t here. It’s a man’s world, where money is the only thing that matters. And, as proven so indelicately here, it matters more than the soul of one sweet, hopeful girl.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- Remade in 1939 as The Panama Lady with Lucille Ball (yes) in the lead role. I guess they kind of have the same eyebrows.

- There is more written about this movie over on Immortal Ephemera than I could ever hope to improve upon, including short bio of Twelvetrees and Bickford. Check it out.

- Mondo 70 disagrees with me on the effect of the film’s finale, finding that it subverts the film’s themes rather than enhances them. Then again, they are with me on Murphy’s skill:

I’m more certain that writer Garrett Fort bit off more melodramatic bs than the actors could chew at the end. Until then, Panama Flo is a mildly interesting look at a virtually unknown director. Ralph Murphy’s filmography is an almost complete mystery to me, but he gives the camera a healthy workout here, especially in the Panama scenes. Beside the tracking shots I mentioned he keeps the camera mobile in Flo’s apartment to dramatic effect when Flo threatens to throw herself out of an abruptly opened window after Dan threatens to have her thrown into a “hoosegow” filled with filthy drunks. Cinematographer Arthur C. Miller combines with Murphy for some nice proto-noirish effects, particularly a shot of a room illuminated only by a moonlit doorway and the moonlight outlining a brooding Flo as Dan enters.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is an obscure one. I wish you luck in finding it!

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|