|

|

|

| Carol Morgan Tallulah Bankhead |

Bill Wade Robert Montgomery |

Peter Blainey Hugh Herbert |

| Released by MGM | Directed By Harry Beaumont |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- The film opens with a montage of newspaper headlines over the years promising that the end of the Depression is at hand. The papers are greeted with raspberries and mocking ‘wah wah wah’ trumpet music.

- Robert Montgomery starts off the picture at an advertising firm that works in the sausage industry. Unsurprisingly, this leads to a number of double entendres such as: “Think of sausages, Mr. Wade, and smile.”

- He isn’t too happy about being asked to smile, and replies, “There’s your smile, and you know what you can do with that!”

- The old “I didn’t think people got married any more.” routine.

- There’s a play on words involving seasickness and a ‘port hole’.

- Drinking will numb the pain.

- Our leading lady Tallulah Bankhead goes from a high society lady to a lady of the night through some pretty rotten luck.

Faithless: A Race to the Bottom

“The world is not itself. The world has changed! And you must change as well!”

Faithless is an odd duck of a film, a movie which takes a fairly standard dramatic plot and keeps pushing it forward, a go-for-broke attitude in a fairly heavily established genre. Spoiled little rich girl learns what life is like in the dredges. Surely there isn’t much new to be gleamed from that story?

I mean, look at those headlines. The Depression ended by 1930, right? …. right?

Weird thing is that Fatihless succeeds because it pushes the matter. This isn’t a woman who returns to her normal life after a brief fall from grace. This is The Great Depression, and her life is utterly, irreversibly ruined. There’s optimism for her future, but she will never be as she once was. Only by agreeing with her lover to forget all the awful things they’ve done is how she endures.

Carol Morgan is that woman, and she begins the movie with millions in the bank. She’s one of the carefree youth, as they were called, whose trust fund is getting precipitously low but her enthusiasm for spending money keeps going up, up, up. She’s head over heals for Bill, an advertising guru whose latest attempts to sell sausages isn’t going very well. It’s not going too well with Carol, either, as she proposes to him but he refuses to marry because he wants her to live on his income. He makes a paltry $20,000 a year (modern money: $282,000 a year); who can live on that?

Uh, not that it matters for long. Carol is told that she’s broke the same day Bill’s firm goes under. Now united in their poorness, they have to start from the bottom– er, oh, Carol is going to go mooch of friends and her family name, actually. When even her name is worthless, she decides she’d rather be the kept mistress of Peter Blainely, a man who utterly repulses her. I mean, check out that kiss to the side.

Peter is played by Hugh Herbert in a rare non-comedic role. Like Guy Kibbee in Rain, the normally rotund and mush mouthed comedian gets to strut his dramatic chops. Instead of befuddlement, Herbert exudes a kind of masculine cruelty that’s chiseled into his face like a rock. When Carol protests that she has a headache and asks “Must I pretend?” he responds, with his grin not even flickering, “Or else!”

One of the few scenes of Peter not chomping down on a big phallic cigar. Then again, he just pushed her over. Has to use his hands for something else every once in a while.

Bill, who has pretty much the worst timing, arrives at Carol’s place. He finds her apologetic, but Peter insists that she stay. Bill, feeling righteous, turns to him. “Mr. Blainey, I don’t know who you are, but this lady happens to be a lady, if you know what I mean, which I doubt.” “Well, Mr. Smart Guy, this apartment happens to be my apartment, if you know what I mean. Which I think you do!” Yowch.

Carol finally decides to stand up for herself, rips off her clothes (unsurprisingly, this is a pre-Code) and heads out onto the street. But no one is hiring a woman who’s pretty and has no skills, even if they sound like Tallulah Bankhead. Poor and destitute, she sells the final symbol of her luxury– a pair of nice shoes– to buy a cup of soup. Earlier in the movie she’d explained that she reviled the stuff, but now it’s the cheap, sweet savior that keeps her alive. She runs into Bill in the restaurant, and they reaffirm their love and agree to get married. A happy ending.

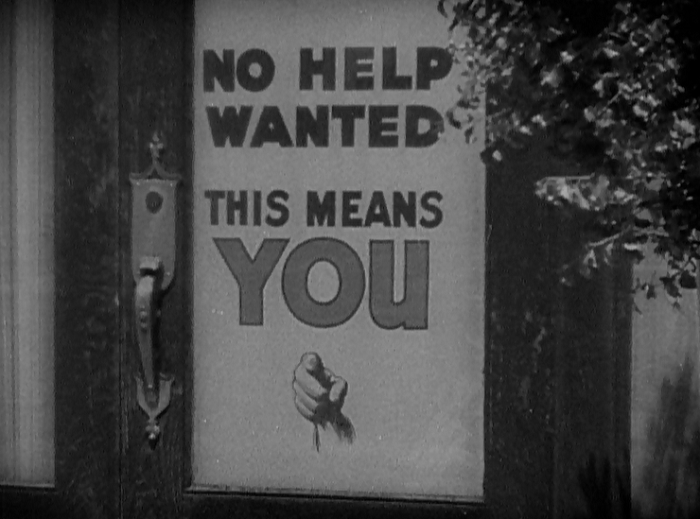

I want you! To scram!

In a normal movie– hell, even usually in a normal pre-Code– this is where the film would close. Carol has fallen from the life of luxury, hitting every stair on the way down. She is literally eating humble soup; it’s the only thing she can afford. She’s learned her lesson, and Bill is there to see her back to stability.

But, nah. The movie has taught her humility, but she hasn’t had to prove it yet. Bill’s latest job goes bust shortly before they’re married. As Bill explains, it’s cheaper to move from place to place than to have to pay rent. He takes a job as a scab, but is injured when striking workers intentionally wreck his truck. Critically injured, Carol has to give up her last shred of dignity and walk the streets to pay for his medicine. It’s a moment of true desperation and heartbreak since she knows that if she does this and Bill ever finds out, it’s not unlikely to believe that he will spurn her for what she’s done, even if she’s saved his life.

Things go from ‘bad’ to ‘oh god no’.

Those final twenty minutes is where Faithless really comes out of its shell, making its main character swallow how it is her own actions that led her to that point where she’s essentially damned if she does and damned if she doesn’t. Her lowest point is when Bill’s kid brother, who’d never liked her much and promised Bill that Carol would someday be a prostitute, sees her walking the streets. Worse, she accidentally tries to pick him up. Worse yet, a police officer sees her doing it.

The story loops back around as the police officer tells her that if the Morgan’s Home for Wayward Girls hadn’t closed, he’d have sent her there rather than take her in for street walking. The final ironic kicker being that that home was actually her father’s pet charity that she’d had closed when it was draining too much money from her lavish lifestyle.

I bring this up because it speaks to what the movie’s trying to do. Carol starts out the movie greedy, rich, and inconsiderate. By the end, she’s become the exact woman she carelessly dismissed as lazy in act one. But it’s not just The Dramatic Irony Gods having their fun with Tallulah like they did back in The Cheat, it’s a comment on how Carol took the trust of her father and abused it. It’s a condemnation of an entire generation of idle rich who had taken the charitable trusts and safety nets of society and flung them out the window for a bigger bank account. Her journey through the film is a punishment for her own arrogance and revenge on how she robbed society by her selfish actions.

Uh, did I say ‘robbed’? I meant ‘borrow discreetly’.

It’s appropriate then that society comes together to get her off the streets by the film’s end. A police officer intervenes and finally helps get her a good, decent job by blackmailing a restaurant owner. It’s not hard to read this as a socialist metaphor, using his governmental authority to force a business to hire this woman. The fact that her forced job apparently helps the business incalculably is even more cheerleading for the oncoming FDR/New Deal onslaught.

Let’s back up and talk about that title for half a tick. Faithless would seem to be an accusation of Carol’s character. She does cheat on Bill, but it’s never something as accusatory and as empty as that title would suggest. I think Faithless is more describing the loss of faith in the established trust of society. Throughout the movie the social order has repeatedly rejected and degraded our leads, offering them hopes and then dashing them brutally. It no longer pays to have faith that things will work out in America– we can only survive until a power greater than the individual intervenes.

Robert Montgomery as the luckless Bill is as charming as ever, both wry and pleasant while deftly suggesting a bit of world weariness as his fall from social graces accelerates. However, Tallulah Bankhead is an actress I’m still not entirely sold on. She seems to have a problem with being subtle on the movie screen, as that exaggerated kiss above shows. Almost every scene where she’s left to her own devices just sticks out like a sore thumb.

This movie is just like the movie Crash! … who am I kidding, no it ain’t.

That being said, I do think there’s some remarkable meat to her performance (even if it is notably similar to her role in The Cheat, up to and including the fact that both characters have rotten luck at roulette). She pulls off that transformation from flighty socialite to the woman who speaks only in regrets with a minimum of scenery chewing. The scene where she makes the fatal decision over what to do about Bill’s ailing health is beautiful in just how desperately she tries to keep her composure as she gets herself ready to become the last thing she’d ever imagined she could become.

Director Harry Beaumont has a very agile camera, using pans to circle around the characters, as if it is either curious or merely stalking them as prey. While I have no doubt there will be many who could write Faithless up as another typical morality play, it succeeds because of its exaggerations of reality. This may not have been how The Great Depression ever was to anyone, but this is how it felt to many– a long series of indignities chipping away at you, payback for something you did that you didn’t even understand once upon a time. Now, after the fall, the only thing we have is each other.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- Stars in Heaven marvels, “There are some scenes in Faithless that may require you to rewind the film to the beginning and see the lion again in order to convince yourself you’re watching an MGM movie.” Though they’re not a fan of the ending.

- Karen seems pretty giddy over this at Shadows and Satin, running down the entire plot with plenty of quotes.

- Mondo 70 seems a bit on the fence on this one. They note, however:

It is a pretty melodramatic and episodic story, and to a film critic it probably would seem like a cliched catalogue of misfortune. But don’t you suppose the Depression was like that for a lot of people? I don’t know if anyone in real life fell as far as Bankhead’s heiress does here, but the point is that here M-G-M acknowledges the misery of the Great Depression in a manner more typical of Warner Bros.

- TCMDB talks about the film and its relation to Tallulah’s nascent Hollywood career:

Despite positive reviews for her work in Faithless, Bankhead wasn’t interested in a contract with MGM or a Hollywood career. Louis B. Mayer wouldn’t meet her salary demands anyway and realized she was a public relations nightmare due to her offscreen promiscuity. Indeed, Bankhead could be unpredictable, hilarious and uncensored in press interviews like the time she said to a reporter regarding the Code, “I have followed Mr. Hay’s advice and have taken up a completely sexless, nun-like, legs-crossed existence.” Simply put, Bankhead refused to play the Hollywood game, called it quits and returned to the stage. She wouldn’t appear in another film for eleven years – a cameo in Hollywood Canteen (1943). However, you can still get a glimpse of the wit and feistiness Bankhead was famous for in the early scenes of Faithless.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film appeared in the Wikipedia List of Pre-Code Films.

- This film is available on Warner Archive’s Robert Montgomery Collection. You can pick it up over at Amazon and Warner Archive.

|

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar!Home | All of Our Reviews | What is Pre-Code? |

8 Comments

Brittaney · May 30, 2014 at 5:35 am

I enjoyed this review and am glad to see you liked the film. I’m a fan of Robert Montgomery and think this is one of his better movies. We get a peek at his dramatic acting abilities that we would later see in Night Must Fall. And oh, that policeman. One of the few spots of sunshine and compassion in this film. Thanks again for your review.

Danny · June 1, 2014 at 3:49 pm

Montgomery is excellent, and does a great job selling his character’s tragedy but who doesn’t lose his spirit. And Night Must Fall is great, too. Thanks!

Vienna · May 30, 2014 at 3:59 pm

Great review and pictures. I think it’s a pity Tallulah and Hollywood didn’t get on. She could have made some great movies.

Danny · June 1, 2014 at 4:11 pm

I can understand why they didn’t get along– she very much had a temperament that didn’t quite match the studios’ speed at the time. But it would have been interesting to see her try and stick around in Code-enforced Hollywood– well, ‘interesting’ or ‘a disaster waiting to happen’, one of those two.

Grand Old Movies · May 31, 2014 at 6:15 am

Hollywood just didn’t seem to know what to do with Tallulah. The only role that seemed to capture her was as the journalist in Lifeboat, and I think that’s because the role allowed her a hint of bitchiness and dry, cynical wit. (Looking at her in the clip above, in which she has to propose to Montgomery and look dewy-eyed and simpering—that just ain’t Tallu.)

And then pairing her with Hugh Herbert…I just can’t picture it. Not just with Tallulah but with ANYONE. I mean … Hugh Herbert!

Danny · June 1, 2014 at 4:19 pm

I think Tallulah, more than anyone, was a few decades ahead of her time. It’s a shame she passed before the 70s, I think a movie that cast her in something like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? would have been amaznig.

justjack · June 1, 2014 at 3:16 am

Love that Tallulah and wild streak. I read somewhere that after she got her first movie contract, she was quoted as saying, “Darling, I’m going to Hollywood and f*** that divine Gary Cooper!”

Someone I read long ago said that the problem with Tallulah and the movies was that the camera just didn’t love her.

Danny · June 1, 2014 at 4:33 pm

That’s a great story. I don’t know if the camera didn’t love her, I just think her image in early 30s Hollywood didn’t match with the times. Like in The Cheat, she seemed too glamorous and too carefree for an era that was neither of those. She may have had better luck in the Jazz Age or in the 70s, but in pre-Code, she was more profane than Mae West with no filter to keep her from drawing scrutiny.

Comments are closed.