|

|

|

| Beatrice Pullman Claudette Colbert |

Delilah Johnson Louise Beavers |

Stephen Archer Warren William |

|

|

|

| Peola Johnson Fredi Washington |

Jessie Pullman Rochelle Hudson |

Elmer Smith Ned Sparks |

| Released by Universal Pictures | Directed by John M. Stahl |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code-ish

- The relationship between two women, one black and one white, and their daughters is fraught with matters of racial tension and identity.

Imitation of Life: Together but Unequal

“It’s like her pappy was. He beat his fists against life all his days. It just eat him through and through.”

Imitation of Life is all about race. It’s not, of course– it’s about motherhood and love, but the fact that we’re watching parallel stories between a white woman and a black one is carefully planted as though it’s an afterthought. But that’s the greatness of early-30s filmmaking: subtle insinuations taking carefully tailored swipes at the unspoken barriers between the races that had lingered on from the Civil War all while still doing their best to get the picture to play in states where the theaters remained segregated.

Let’s start with that story. After the death of her husband, Beatrice Pullman (Colbert) is struggling to make ends meet. She’s a maple syrup salesman but also has to deal with her young daughter, Jessie, who gets into increasing amounts of trouble. One morning, Delilah Johnson (Beavers) arrives at her house, confusing addresses for a place she wanted to get work as a domestic. Seeing the chaos, she swoops in and helps out. For board and food for both her and her young daughter Peola, Beatrice agrees to let her stay.

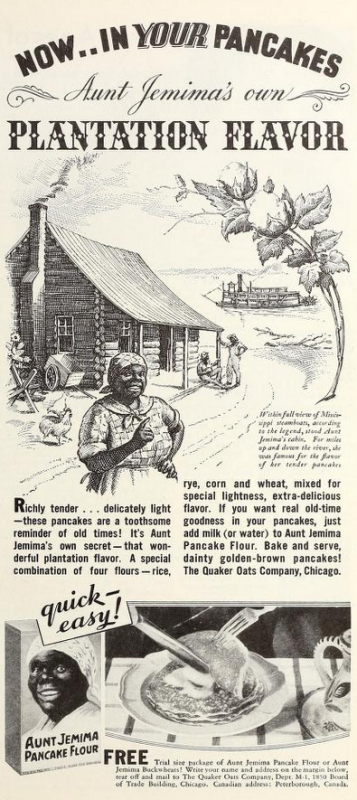

The next morning, Beatrice samples Delilah’s pancake recipe and a light bulb pops up above her head. She heads down to Atlantic City’s boardwalk and puts the pieces in motion to open a pancake restaurant. Her reasoning is that it will help her push her maple syrup. What Delilah feels doesn’t really enter the equation– imagine a friend coming home and tell you that you’re going to be chef at a brand new restaurant, and, oh yeah, our entire financial future depends on its success. Delilah does exactly what’s expected of her and goes along with it. After a few years, the two hit it big with a packaged version of Delilah’s pancake mix, with her big hammy mug lighting up billboards across the city.

Were that their personal lives as easy. Their daughters grow up together, but Peola has a far harder time with things. Light enough skinned to pretend to be white, Delilah discovers with some dismay that Peola has been ‘passing’ just as such. It breaks Delilah’s heart, but as they grow older, Peola’s desire to assume the whiteness that her skin grants her grows as well.

Delilah and Peola can’t meet on any level. Where Delilah sees subservience as her life’s duty, Peola sees privilege and acceptance glimmering just inches from her grasp. She constantly rebels, going so far as to drop out of an all-Black college and take a job as a cigar girl in a restaurant where she can be white and “normal”. Her mother and Beatrice find her after a frantic hunt, only to have Peola cry to a stunned patron, “Do I look like her daughter? Do I look like I could be her daughter?!”

Back in their elaborate mansion that the two families share in New York, where Delilah still occupies a windowless servant’s quarters and Beatrice has a veranda with a magnificent view of the Brooklyn Bridge and the stars dancing around the night sky, Peola lays it out to her mother. She’s going away, and she’s never coming back. She’s not a black child any more. Delilah, who has had bouts of sadness but held her emotions tightly throughout, finally loses it in a moving scene:

“I bore ya! I nursed ya! I love ya… I love ya more than you can guess! You can’t ask your mammy to do this! I ain’t no white mother! It’s too much to ask of me. I ain’t got the spiritual strength to be that. I can’t hang on no cross! I ain’t got the strength! You can’t ask me ‘ta unborn my own child!”

Peola’s predicament couldn’t help but remind me of Inherit the Wind, an admittedly very-white movie about a fictionalized version of the Scopes Monkey Trial. The defendant, a school teacher, reconsiders her push for innocence for teaching Darwin in the classroom and his defense attorney, Henry Drummond, points out that he must have “the loneliest feeling in the world.” But he adds:

But all you have to do is knock on any door and say, “If you let me in, I’ll live the way you want me to live, and I’ll think the way you want me to think,” and all the blinds’ll go up and all the windows will open, and you’ll never be lonely, ever again.

Peola doesn’t want to be lonely, but more to the point, she doesn’t want to be black. What is her mother’s blackness to her? Delilah has remained steadfastly subservient to a woman who’s been exploiting her her entire life. That Beatrice is also her best friend and benefactor makes the pill easier to swallow, but Delilah is the opposite of proactive about anything in regards to her station in life.

When Delilah was told that she’d be getting 20 percent of the profit from the incorporation of her pancake mix business (20 percent), she refuses it, terrified that it means she will be separated from Beatrice and Jessie and could no longer be their domestic. “I’se your cook and I wanna stay your cook!” she insists. Beatrice still helpfully offers to invest Delilah’s dividend, but come on. Delilah is an antebellum poster child, a shuffling mammy who is loyal and generous to a fault, perpetuating all of those stereotypes that echoed through classic film and literature.

On the other end of the equation, the glamorous Colbert also doesn’t age in the least through the nearly two decades covered by the picture– Beavers does, quite visibly, though. She bears her burdens, she carries the pain of her dead husband and knows that fighting back is fruitless. White people and black people are different in her view, and it’s the black man’s burden to carry the whites and suffer their whims.

That Beatrice never pushes back against this attitude speaks volumes to how accepted this is among whites; one moment that jumped out was when Jessie returns from college to find Delilah destitute about Peola’s betrayals. Jessie approaches the grieving mother and instead of embracing her, holds her by the hand and shoulder, guiding her. It’s a patronizing gesture to a woman she’s known since grammar school, but one that raises no eyebrows from the gathered.

Spoilers.

In a mess of melodrama holy holies, Delilah dies of a broken heart. Peola returns in time for the funeral, a massive procession in tribute to a woman who was devoutly religious and whose faith was all she had. Vadim Rizov at Mubi puts this better than I ever could:

The main issue in both [this film and the remake] in the black story is the light-skinned daughter’s desire to pass for white. It leads to tragedy in both cases (the mother up and dies out of grief), but the implications are decidedly different. Delilah’s willingness to be whatever her mistress wants her to be is an understandable affront to her daughter; the only reasons she offers against passing are that it’s wrong and God must have had a reason for making them black. She’s an advocate of righteous suffering. Stahl’s Imitation never even so much as hints at the possibility of racially motivated violence; instead, there’s a sense of Peola longing to escape the dreary confines of her supporting story into the glamorous social melodrama Beatrice and her daughter unthinkingly inhabit. The corrective’s at the end, with Delilah’s lavish, long-planned funeral: for once, the white folks shut up and fade into the background of a majestic parade, with understandably furious-looking extras parading on their own terms through the screen. (The romance gets the last scenes though.)

Peola’s return is frustrating, because on one hand, via dramatic necessity, you want to see Peola come back and realize that rejecting all of these things that are part of her past and history destroyed the beliefs her mother held so dearly. On the other hand, you may yearn for her to simply burn the church down as it stands as a symbol of a misguided subservient life that led straight to the grave. Delilah shouldn’t put up with the shit she does, and we, nearly a century removed, know that. Peola knows it more than anyone else in the movie, but she can’t say it. Not there and then. It’d be a handful of decades before those words could grasp onto a movement.

Judging from reading a dozen or so reviews of this film, your feelings toward it will be directly related to how you feel about Delilah and Peola. Louise Beavers, who any fan of 30s cinema will have seen in a dozen domestic roles at one point or another, brings Delilah to life. Just from the opening moments as she approaches a screen door, Beavers is filled with a light. You get the feeling from her that she’s waited years to take this stereotype and layer something deeper, something tragic to it. Peola, played by real life light skinned black woman Fredi Washington, has a real rage brimming under the surface that few actresses got the chance to demonstrate.

The companion story line, of Colbert dealing with her daughter’s feelings for her lover, is less interesting. That’s probably because the stuff that would titillate current audiences– Colbert’s apparent control and domination of a then-modern baking empire– is swept under the rug in favor of the usual romantic gloss and cheese. For a movie about a successful female business magnate (Archer even bemoans at one point, “These big business women scare me to death. They’re so efficient– and so competent!”), we never actually see her in her office. It’s a real shame, too, since the early scenes of Beatrice’s business acumen (and fluttering eyelashes) hint towards a gentle ruthlessness, a wolf in sheep’s clothing compared to the balls-to-the-wall sexual powerhouse Ruth Chatterton plays as a female honcho in Warner Bros.’ Female.

Though I do like the contrast between the two romantic leads — Archer is a college educated single white man whose career studying fish apparently affords him wealth and freedom, while Colbert elbowed her way up from the dredges. There’s another interesting little piece of social commentary when Jessie returns from college and segues into dropping out because she’s met a boy. Her mother doesn’t panic or get angry, she just smiles– that’s what college was for for women back in those days.

The cast in this one is great, with Warren William (who also had a doomed romance with Colbert in Cleopatra the same year) having fun as a jaunty, goofy scientist. The lead actresses are all pitch perfect, and, of course, is there any film Ned Sparks doesn’t infinitely improve?

Imitation of Life is a deeply interesting movie, but only if you go in knowing that it’s not something you just watch. It’s something you have to absorb to fully understand, to mentally push back the clock and see the ways things have changed and how they haven’t. Give the filmmakers some credit, too: they knew that sending Peola back to school and ending her obsession with passing wouldn’t turn her into the sad stereotype of her mother. It would give her something to strive for. One is left wondering if white girl Jessie got anything real out of the experience at all.

Gallery

Click for big.

Trivia & Links

- Based on the 1933 book by Fannie Hurst (and, from what I’ve read, it’s a fairly faithful adaptation). Remade in 1959 with Lana Turner and Juanita Moore by Douglas Sirk.

- And, yes, Delilah is a goof on Aunt Jemima. The character of Aunt Jemima was, as I’m sure you already knew, inspired by a minstrel show performance in 1889, where an Aunt Jemima was played by “a white male in blackface, whom some have described as a German immigrant.” Yay, American history. Quaker Oats hired several actresses to portray the character during their product’s production. As then-recently as 1933, Americans visiting the Chicago World Fair would have seen Anna Robinson selling the pancake mix in-character. Failing that, they could have also just opened a nearby periodical. Here’s advertisement from that year in The New Movie Magazine:

- Some background on the book from TCMDB:

Not many people know that the actual inspiration for Fannie Hurst’s novel Imitation of Life came from a road trip to Canada that the author took with her friend Zora Neale Hurston, the acclaimed black short-story writer and folklorist who wrote Mules and Men (1935), a non-fiction study of black culture in Florida, and Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934), a novel about a black preacher. Hurst had originally planned to call her novel about Bea and Delilah, Sugar House, but changed the title to Imitation of Life just prior to publication.

- Ferdy on Film puts a lot of my thoughts together more elegantly than I did:

Delilah’s attempts to get Peola to accept who she is arise from her deep faith. She believes God made folks black and white for a reason and that it is nobody’s place to question that decision. Beavers makes Delilah’s professions of faith so effortlessly sincere and idealistic that she manages to flesh out her character and provide some believable motivation for her acceptance of a second-class role in Bea’s household and business. When, in the end, she is given the grandest funeral New York has ever seen, the film brings into focus the success of Delilah’s lifelong goal—her glorious assumption to heaven. That Bea honors her wish to keep house and accedes to her decisions about her daughter, for example, suggesting Delilah send Peola to an all-black university in the South, may seem as though she is reinforcing the limitations on the black community. Yet I felt more camaraderie between her and Delilah, a shared fate as widows and mothers, than would be evident in the 1959 version.

- Immortal Ephemera has a full biography of Louise Beavers up, and it’s a fascinating read. She was the most famous black actress up until Hattie McDaniel, which was especially sad since Beavers had been the overwhelming favorite for the part of Mammy in Gone With the Wind until McDaniel’s casting. Cliff has a ton of stuff about the film’s background and just how tough it was to follow up her work in this movie, and it’s well worth a read.

Jimmie Fidler, writing of Hattie McDaniel’s 1936 ascent into parts once filled by Louise Beavers, said Imitation of Life ruined Beavers, “because, of all idiotic reasons, she was too good!” Fidler explained, “any actress who can steal a picture from Miss Colbert will be given few chances to steal from other stars, if the others have anything to say about it, and they generally do.”

- Andre Sennwald in the New York Times didn’t really get much out of this.

On the whole the audience seemed to find it a gripping and powerful if slightly diffuse drama which discussed the mother love question, the race question, the business woman question, the mother and daughter question and the love renunciation question. Of these the race question promised to be the most interesting, but the photoplay was content to suggest that the sensitive daughter of a Negro woman is bound to be unhappy if she happens to be able to pass for white.

- DVD Beaver has a bunch of screencaps of the blu-ray for your viewing pleasure.

- Some more reviews from FilmFanatic.Org and Everson’s Film Notes.

- Antonia Carlotta talks about the film’s racial issues in these YouTube videos:

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is available on Amazon (with its remake) on DVD, Blu-Ray, and on its own to stream or purchase digitally.

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Comments

Jeannie · May 6, 2016 at 1:46 am

I loved the friendship between Beavers and Colbert at the start of the film, because they seemed like real women, helping each other out, without regard to race. But once the pancake empire took off, and Beavers claimed she didn’t want any money for it because it was soooo awesome to live in the basement & cook for Colbert, I felt the movie lost its way. Still, for 1934, it’s great to see the two actresses co-starring and dealing with racial issues, head on.

Danny · May 23, 2016 at 6:18 pm

I agree, they seem much more playful at the beginning. But I think the film smartly has them grow slightly apart as wealth flashes its wares at Colbert and she eagerly dives in. Beavers’ character’s religious convictions tell her to resist and the point of life is to work in steadfast servitude. It’s messed up (then and now), but that’s who they are.

La Faustin · May 6, 2016 at 2:24 am

There are a couple of very significant differences between the book and either adaptation: (1) in the book, the white mother loses the man she loves (I believe he’s actually her assistant, shades of MAN WANTED) to her daughter. I can’t remember if the man is even aware that the boss is romantically interested in him. So both mothers, black and white, sacrifice and break their hearts for their daughters. But, of course, a Hollywood star cannot be rejected for a supporting player! (2) In the book, Peola falls in love with and is proposed to by a white mining engineer who is going to work in South America. He doesn’t know she’s black. Peola tells him she can’t have children; when he accepts that, she secretly HAS A HYSTERECTOMY so she won’t produce any more mixed-up mixed-race children, marries him, and goes off with him to South America where no one will know her secret. That’s the last we hear of her. No returning daughter at the funeral.

Danny · May 23, 2016 at 6:18 pm

JEEZ. Okay, very good to know, thanks for sharing!

La Faustin · May 6, 2016 at 2:26 am

Also: comparing the two film versions (on race relations, women and work, etc.) is mind-blowing. Do step out of your era and screen the Sirk!

Danny · May 23, 2016 at 6:19 pm

I probably will when I have time!

Patricia · May 6, 2016 at 3:47 am

The scene in which Colbert and Beavers separate after a conversation, with Beavers heading downstairs, and Colbert up always spoke volumes to me about the relationship of these women.

Comments are closed.