Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- One of my favorite quotes about the Production Code comes from Wikipedia (I know, I know, I also develop treatises on moral philosophies from IMDB comments) when it summarizes an opinion piece from Nation: “if crime were never presented in a sympathetic light, then, taken literally, ‘law’ and ‘justice’ would become the same.” This movie is in open defiance of that, questioning how justice really functions when personal interest is involved, something that definitely could not be explored just a few short months after this film’s release.

- Stella (Fox) is so desperate to hold onto boyfriend Gar (Bogart), she offers to do anything for him, with or without being married.

Midnight: Truth and/or Justice

“It often happens the law is better served by applying the spirit rather than the letter. Whatever may happen in any particular case, justice is done.”

Some movies aren’t for everyone. I don’t say this as a snob, but as a matter of truth– you don’t like every genre, every director, or every style equally, do you? If so, congratulations, you’re probably very boring at cocktail parties.

Midnight is kind of a weird one– it’s for people who like to think during movies. I don’t mean this as a slight, but if you saw Bogart’s face up top and think this’ll be anything like The Petrified Forest or even Black Legion, you’re in for a severe disappointment. If you don’t know what either of those two movies I just mentioned are, get thee out of here and get to work on your Bogart movies, young one.

Ethel Saxton, not having the best of days.

No, Midnight nowadays seems very carefully composed for people who like to look at the way films are built. How tension is constructed and maintained. Why characters behave a certain way and what the film’s moral asks of both the characters and the audience– and whether you agree or not. It’s a movie about two deeply contentious issues– the death penalty and justice– that punishes the character who is both’s most stringent supporter. The plot is contrived, and the acting measured– again, not for everyone– but the directing is inspired and the conclusion haunting.

But before we get there, let’s talk about that plot. Midnight opens with a slow pan around the courtroom of an audience is in rapt attention of a woman’s testimony. She’s Ethel Saxton (Helen Flint), and the camera will get to her last. She discovered that her husband, who she’d adored, is at the bank withdrawing their savings account to run off with another woman. She guns him down. And as she says this, the jury foreman, Edward Weldon (Heggie) stands up and asks her a pointed question– did she take the money after she killed him? She did, and he sees that as all the proof he needs that it was premeditated and that she’s guilty of murder. The jury heads back to deliberate, but the courtroom is so assured of a quick verdict, no one leaves their seats.

Edward needs to find ‘the truth’, and fit it into how he sees the law.

The District Attorney, Plunkett (Johnston), refuses to comment on the outcome of the trial, even after Nolan (Hull), a particularly cynical reporter, pokes him about how the casewill make him a household name. Plunkett notes with an air of pomposity, “The public is always interested in something that affects public morals.”

Nolan sniffs. “Public morals? It’s just good entertainment.”

Back in the jury room, the hands that had been wringing earlier are now bored. One pair makes cutout snowflakes, another doodles. Whatever care was being taken to deliberate the life of this woman has been drained away to tedium, with the implication that Weldon had railroaded the group into his point of view. If she took the money, it’s premeditated. Saxton must go to the electric chair to pay for her crime.

“Tonight? But I haven’t bought my Ethel Saxton Dies Day presents yet!

Four months later and we pick up the story again. It’s the night of the execution, and reporters have camped outside of Weldon’s house, determined to get the scoop on his reaction to the verdict he seemingly wrought. The Weldon family is in a bit of hard times, and the furor over the verdict has put Edward on edge. He complains bitterly to his wife (Margaret Wycherly) as he pours over the newspapers that are sensationalizing Saxton’s final days:

“What bunk. Pages of it. They make her a heroine. Her husband guilty for making her kill him.”

“Things ought to be more dignified. The way it was at the trial.”

Besides his adoring wife, his household is also populated by his adult children, including a daughter, Ada (Katharine Wilson), married to good-for-nothing Joe (Lynn Overman), a carefree party boy, Arthur (Richard Whorf), and his darling youngest daughter, Stella. At the trial, Stella had met Gar, a low class hoodlum, and the two hooked up, leading Edward into no end of frustration– he believes in the letter of the law, and the last child he has any hope for is flouting it.

This movie contains more kisses before the mirror than The Kiss Before the Mirror (1933)!

Arthur departs for the evening, while Nolan pays the weak willed Joe to allow him into the household as a ‘friend’. That night, the McGraths (Cora Witherspoon and Granville Bates) come to play bridge in order to help Edward take his mind off things, but it goes nowhere. Every move he makes seems to be echoing the same ones Saxton is making on the other side of the city. Told in a slightly-sped up version of real time, we’re trapped in the parlor as Edward tries to forget what’s happening due to his moral judgement. Nolan pokes at him, too, further putting him on edge.

Edward’s pacing transposes onto Ethel’s.

Elsewhere, a date between Gar and Stella isn’t going well. Gar is the kind of guy who goes and sits in the front rows of murder trials just because he finds them interesting. Maybe it has something to do with his line of work, maybe it doesn’t. But while he’s a gangster eager to make his ‘first million’, he’s also genuine and sweet to Stella. Unfortunately, he’s also not too into being tied down to any one woman, which comes as a shock to her after four months of courtship among other things. As he prepares to head to Chicago for ‘business’, she becomes practically frantic.

Chester Erskine is an deft director, using quicker paced cuts as the film’s switch happens. At the stroke of midnight, Edward finally loses his composure. Saxton dies. And a gunshot rings out. Fans of 1930s melodrama know that just as Edward is making his final statement on how justice must be blind to emotion, his own daughter is committing a crime of passion and pushing him onto the other side of the issue. In a situation where his emotions can’t be separated from his beliefs, does he still value the cold word of law as a way to punish the guilty?

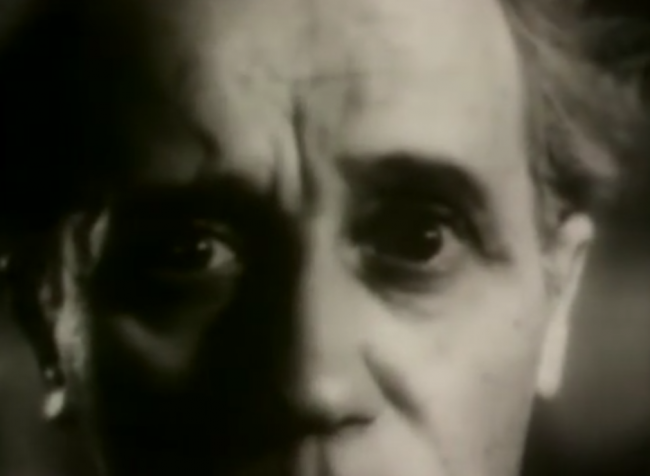

A closeup of Edward as he learns of the film’s major plot twist.

Spoilers.

Nolan knows the real answer, even as Edward refuses to lie for the shaken Stella about whether or not she was provoked by Gar. Nolan calls up Plunkett and asks him to come by the house, with Edward hoping that being truthful will grant her leniency. Plunkett, though, knows that this trial could cast doubt on the Saxton verdict and throw his career ambitions out the window. Through a careful series of questions, he concludes that someone else must have killed Gar as part of a gang fight and leaves, promising the Weldon’s that they won’t be bothered about it.

A rare moment of rack focus in early 30s cinema.

Erskine does some really interesting stuff at a time when a lot of directors were mostly considered with making stars look good than with kinetic motion. Erskine focuses on body parts and draws parallels– the hands of the jury and Joe playing pool, the restless feet of Saxton and Edward, and the chests of two police officers– one guarding Edward, the other watching Saxton in her final minutes. There are also mirrors everywhere in the movie, with Edward constantly plagued by his own reflection.

Unfortunately, while an interesting and illustrative technique, it also makes the film feel academic in several places. The real obvious reversal, which isn’t hard to guess, underlines it, making the movie seem more like a parlor game setup for discussion rather than a satisfying narrative.

On the other hand, it’s saved by some excellent acting. I’ve seen some people lament the ‘silent’-esque acting here, and I’m here to tell you those people are idiots. While it’s not as zippy as a Warner Brothers movie, what struck me about the film is that you can see the characters gears turning in their heads. Especially great is Moffat Johnston as Plunkett, the rare time in a movie where a lawyer is allowed to manipulate the law so smoothly and smartly with nothing but logic and conjecture. And by the end he has a smile on his face.

What does Edward learn about justice from the film’s conclusion? He’s holding his daughter, thankful that she’s been saved, but devastated that he essentially doomed another woman by not looking at it from her point of view– and by refusing her any sympathy.

End spoilers.

Figuring out some version of the truth.

This still leads to broader questions, outside the film’s acknowledgment that justice is malleable. How just is the death penalty? Is the death penalty suitable punishment for a spur of the moment irrational act? And can any act be seen as just when incriminating events can be reinterpreted after the fact to suit a narrative by the powerful? It’s easy to appreciate how deftly Midnight arranges all this, calling on the audience to decide for itself if and how justice works and whether it can ever truly be fair. Laws and guidelines are built as a framework, not the final say in moral law.

While it’s not as much of a shock to the senses as White Zombie or as ambitious as The Sin of Nora Moran, Midnight further proves how willing independent productions were willing to push things stylistically to compete with the major studios. Midnight isn’t going to be everyone’s cup of tea, but it’s a fascinating example of a talky, meditative movie that asks a dozen unpleasant questions before stalking off into the night, puffing a cigarette.

Trivia & Links

- The movie seems to get an unfair share of negative critiques from its post-release marketing– the credits on a reissued version from 1947 (renaming the movie to Call It Murder) and many DVD covers place Bogart front and center in hopes of cashing in on his name. As happens so many times, while it got people to watch it, many felt ripped off. Being in the public domain, this effect is worsened as many shady distributors seek to squeeze out a penny for their own ends.

- Some people are huge Humphrey Bogart fans (don’t ask me) and one of those is the person who runs The Bogie Film Blog. They’re pretty down on the film, rating it 1/5 Bogies, though they like the chemistry between Bogart and Fox.

More Bogart in case you need it for some reason.

- In one of the indescribably rare occurrences on the site, I’ll link to a DVD Verdict review that’s actually not that bad.

Midnight, despite its stagy limitations, does tell an interesting story concerned with the issues of social conscience and justice. In that respect, it is much in the same vein as many socially conscious films of the early 1930s—films focused on issues of the day or “torn from the headlines” as WB liked to advertise its product. Edward Weldon is a man who believes in the letter of the law and when he perceives that justice is not being served by the actions of legal counsel in the Ethel Saxon trial, he speaks up to ask the damning question whose answer condemns Ethel in his mind. Having so decided, he proceeds to lead his jury members to reach a guilty verdict. It is thus ironic that he is faced with a comparable situation when his own daughter apparently kills her boyfriend in another “crime of passion.” Midnight does a good job of building the pressure on Weldon as the execution hour approaches through a variety of plot devices involving different members of his family and interesting lighting and editing techniques.

For a somewhat minor film, the latter are fairly unusual. Director Chester Erskine (listed in the opening credits as Chester Erskin) tended to be multi-threat guy in his career, often writing as well as producing, as he does with Midnight. The film was in fact his directorial debut and it seems clear he was quite influenced by German expressionism of the 1920s. His use of shadows and unusual camera angles is striking and his compositions are out of the ordinary. For example, the opening sequence presents a succession of shots showing the faces of everyone in the court with the exception of the main person involved—the testifying witness. On another occasion he uses the buttons and shield on a police uniform as a focal point to cut from one policeman standing guard outside the Weldon home to another standing guard outside Ethel Saxon’s prison cell and then back to the Weldon home.

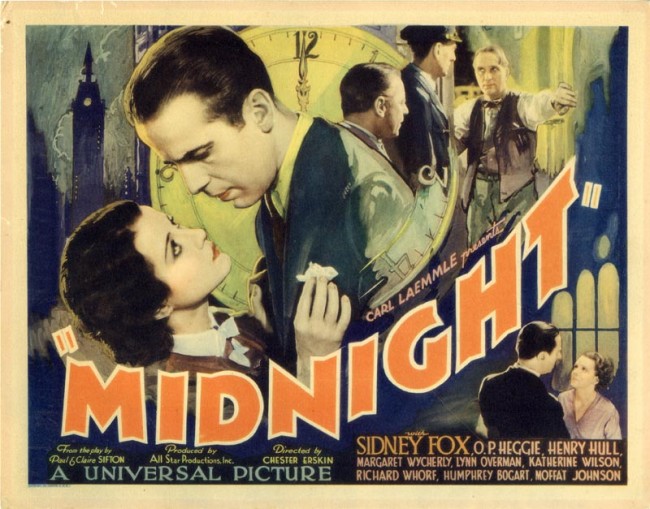

- The film’s lobby card for its original release is pretty nice looking, though it seems to lack Edward altogether:

Awards, Accolades & Availability

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Comments

Judy · June 20, 2015 at 3:16 am

I remember seeing this under the ‘They Call It Murder’ title in an official DVD which looked like a really bad bootleg. It was almost unwatchable, so I couldn’t come to any sensible conclusions about the film’s quality, although I was impressed by a few scenes even so. Did you find a release with a decent print, Danny, and if so which one was it? Thanks.

Danny · June 20, 2015 at 10:10 am

As you can tell from the screen shots, a good looking print is hard to find. I think this one is going to languish in it, too, since it was an independent production distributed by Universal, so no one really has a horse in the race. Too bad, too. The screenshots are from the YouTube version I linked above, I believe.

Judy · June 20, 2015 at 10:35 pm

Thanks anyway! A shame, it could do with being cleaned up and presented properly. I might try the YouTube version.

La Faustin · December 2, 2016 at 3:58 pm

There’s now a sharper copy on youtube — thank you, Universal Vault! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3jSecCkNK8&t=2634s

Comments are closed.