|

|

|

| Dixie Dugan Alice White |

Jimmie Doyle Jack Mulhall |

Donny Harris Blanche Sweet |

| Released by First National/Warner Brothers | Directed by Mervyn LeRoy Run time: 80 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- “The moment he meets a girl, he starts feeling her ribs!”

- “You know what great pictures he’s always made.”

“It ain’t pictures he’s thinking about making now!”

- Dixie throws on her kimono as she crosses the room.

- The final number’s backdrop is a rainbow of women lifting up their dresses and bending over. (Or it would be if the color version survived.)

Show Girl in Hollywood: Hitting the Notes

“You’re a very clever little girl!”

“Sure. So was Joan of Arc.”

Hollywood in 1930 was chaos and turmoil. Sound was the new normal, and that meant chaos in building stages, finding new stars, and putting some of the old ones to rest. Show Girl in Hollywood is an interesting artifact of that transition without explicitly saying that that is what it’s about. Here you have a silent starlet in a big musical extravaganza flanked by a few other star hldouts all involved in the process of making a picture. Some are destitute, some become destitute. That’s Hollywood for you.

Alice White is Dixie Duggan, a childlike waif who is guaranteed of stardom as soon as she gets her break. Unfortunately, standing between that is sleazy director Frank Buelow (John Miljan), a smooth talking egotist who mostly just likes to thwart others. Luckily, studio head Mr. Otis (former Keystone Kop Ford Sterling) grows fond of Dixie and puts her in a film adaptation as the leading lady in Rainbow Girl, a show she’d be an understudy in back on Broadway. Her gee-shucks boyfriend Jimmy Doyle (Mulhall) wrote it, and things look swell until Buelow interferes again just to show off that he can.

The movie definitely projects the vibe of being a puff piece for Warners’ Vitaphone sound-on-disc process, with White even defiantly declaring at one point:

“I’ll be speaking to you– and all the rest of the world– over the Vitaphone!”

Show Girl wants you to know how movies are made– it’s fascinated by the process of talking picture talking. A number in the middle of the film, “I’ve Got My Eye on You”, weaves in and out of behind-the-scenes looks at the number’s recordings. This includes inside the massive recording ‘blimps’ containing the cameramen, men checking the recording discs, and even a few shots of the massive orchestra right off screen. It’s wonderfully evocative of how much of an intensive process film making is, moreso than the final result of this picture.

I apparently have a much wider berth for my tolerance for Alice White in the movie than a lot of other reviewers. Her eyes move with confidence, even when the rest of her slippery frame seems unable to keep up. White’s performance here is definitely a rough outline for what Marilyn Monroe would later trade upon for fame and fortune– baby doll, beach blonde sexy that is dim with a hint of wit. Unfortunately, Monroe didn’t pull it off in every movie, and White doesn’t get much help here. She alternatively seems too much like a child and then too much like a sexpot, and there’s nothing in between. It’s hard to empathize with a character when you can’t tell if they’re bringing it on themselves, especially in a scene like one where she tears apart a room like an angry toddler.

That can make the movie kind of grating, especially compounding the fact that she isn’t much of a singer, which, as we all know, is usually a liability in a musical. But the film’s biggest flaw has to be structural– is this a comedy about a showgirl who is a little too easily influenced, a musical tragedy about Hollywood’s good and bad sides, or a drama about how a dumb kid saved an old star? It’s hard to care about White’s character when she comes across as so inherently stupid about the ways of the world, and most of the other characters, while fine in bits, don’t really stand out.

The only exception is Blanche Sweet as the washed up movie star who Dixie befriends, the only person other than White to get a musical number and the subject of several very beautifully moody shots from director Mervyn LeRoy. Her sad story, which includes selling off rooms full of furniture to maintain appearances around the money-obsessed city, ring a number of sad notes that would later be ghoulishly exploited in the likes of Sunset Boulevard. Here, though, they are wallpaper to Dixie’s upbeat adventures, which creates a tonal clash to say the least.

Overall, Show Girl in Hollywood is probably worth seeing for people fascinated by the transition to talkies, as it both inside and outside demonstrates the difficulties of adjusting to the new processes. The production design is also nice, and Blanche Sweet’s role will reverberate. But the movie itself is just kind of oatmeal beyond that.

Gallery

Click to enlarge. All of my images are taken by me– please feel free to reuse with credit!

Trivia & Links

- Sequel to Show Girl (1928) also with White, which was considered a lost film until 2015. Hopefully it will get a release via Warner Archive soon!

- The last 10 minutes of this movie were originally screened in two-strip Technicolor. Unfortunately, the sequence only survives in black and white.

- Just to reinforce its Tinseltown roots, the film includes brief cameos of Al Jolson, Ruby Keeler, Loretta Young, Noah Beery, and Noah Beery Jr. as the film wraps up.

- Mordaunt Hall wasn’t a fan:

In film form this story is somewhat puerile, one in which subtlety is conspicuous by its absence. Intended shafts of satire emerge as bludgeon-like humor and when attempts are made to draw a tear or two one is apt to become more aggravated than sympathetic, especially when music is called upon as if to soothe the savage breast of the spectator.

- Ferdy on Film echoes a lot of other reviews in their assessment of the cast:

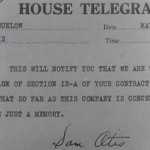

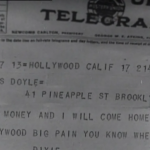

It’s hard to get around the big lump of awful that is Alice White—the endless close-ups of her Kewpie-doll face in her odd cloche hats start to cloy as much as the very odd turns of phrase she uses—but there is actually quite a lot of great in A Show Girl in Hollywood. For starters, the rest of the cast is wonderful. For example, Ford Sterling makes the most of the snappy script, the delights of which I can barely scrape at here, and delivers large doses of perfectly timed comedy with a dash of realism. When Dixie storms Otis’s office to tell him she has come all the way from New York, he merely walks to a door and opens it, revealing a waiting room full of young women who have done exactly the same thing. When provoked, he very understatedly pulls out a piece of paper and pen to write the note informing Buelow, and then Dixie, that their services are no longer required (“it is as if you never existed”). Shortly thereafter, the only man (Billy Bletcher) whose job is assured at the studio—the man who paints on and removes employees’ names from their doors—comes by and makes the characteristic and humorous scraping noises that signal a change in the air.

- This movie didn’t end well for anyone‘s careers, with Mulhall and Sweet both declaring bankruptcy within two years and star Alice White falling heavily from grace with Warner Bros. by the end of 1931. Immortal Ephemera goes into the many fascinating ins and outs of the film. He concludes:

Show Girl in Hollywood remains a fascinating film even if it is buoyed more by the trivia not only surrounding it, but unfolding within it, than it is by virtue of its actual content.

If you happen to like Alice White than Show Girl in Hollywood can’t miss. If you’re not a fan than this isn’t the film that’s going to turn you into one. All of her weaknesses are on display.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

More Pre-Code to Explore