|

|

|

| Pancho Villa Wallace Beery |

Rodolfo Leo Carrillo |

Teresa Fay Wray |

|

|

|

| Jonny Sykes Stuart Erwin |

General Pascal Joseph Schildkraut |

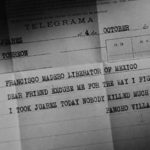

Francisco Madero Henry B. Walthall |

| Released by MGM | Directed by Jack Conway Run time: 115 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- People are murdered pretty indiscriminately– this is a revolution, after all. We see plenty of hangings, while innocent people are killed, beaten, and raped as examples to others.

- Pancho Villa’s major hobby is getting married to beautiful senoritas and having a lovely honeymoon before running off to the next marriage.

- Who hasn’t wanted to see Wallace Beery wearing just a towel?

- There’s one scene with Fay Wray and a whip– I’ll go into it below. It’s nuts.

- A naive reporter from “The Saturday Evening Post” shows up in safari gear to cover the war. Sykes warns him, “You better hide that hat– they’re short of modern conveniences in these parts.”

- The film’s villain gets a particularly gruesome death. And we get to hear his blood-curdling screams too!

Viva Villa!: Nos Salvará

“Forgive me? … Johnny, what’ve I done wrong?”

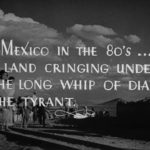

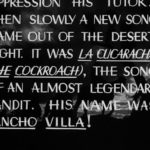

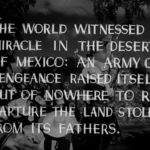

Viva Villa! is nothing short of a pre-Code epic. Running nearly two full hours, it was shot on location, it has hundreds of extras, some very big stars emoting very bigly, and the fate of a country at the center of its story. And it begins with a handful of dirt– that’s the last thing that Pancho Villa’s father is grasping when the land-owning major domos evict the peons from their land and execute the only one who dares to stand up to them. Pancho takes to the hills, grows up to be a bandit (and Wallace Beery), and soon finds himself called upon to help rid the country of the Spanish-born domos and restore Mexico to its native people.

It’s 1910. There are two other figures in this revolution, the politician Madero (Walthall) and the cackling General Pascal (Schildkraut). Madero is filmed with soft light, and the film’s staging makes him out to be very much a Christ-like figure. And we all know what happens to those people. Pancho serves Madero proudly and chafes under Pascal, all while bringing the revolution much-needed victories. He’s accompanied by murder-happy Rodolfo (Carrillo) and drink-happy press agent Sykes (Erwin).

Villa’s leadership style is suspect. He usually crashes into a scene ordering people to “SHUT UP! SHUT UP!”. He has the subtlety of an ox but is humble at his own accomplishments– save when it comes time to get the senoritas to marry him. This inspires loyalty, as does his ruthlessness. He clashes with Madero in his methods, which the film’s screenwriter, Ben Hecht, uses to lay the film’s morality out:

Madero: “You’ve brought disgrace on the revolution. You made war not as a soldier, but as a bandit.”

Villa: “Oh, Mr. Madero. What difference does it make in how we win wars? If the other fella wins, why then, that’s not so good.”

Madero: “You permitted the killing of the wounded on the battlefield!”

Villa: “Mr. Madero… what are we going to do with these people? I don’t think you know much about war. You know about loving people. But you can’t win a revolution with love, you’ve got to have hate! You are the good side… I am the bad side.”

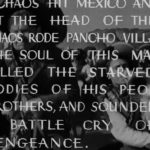

Pancho Villa has rough edges to spare, and while the movie makes him laughable and a comedian as often as not, there is serious darkness swirling underneath his buffoonish visage. He knows his blood-covered fists are the only thing that can bring reform to Mexico, but he tempers this with his love and faith in Madero. When the revolution is a success, Villa steps out of the picture. But Madero is outmatched by the old rich of Mexico and assassinated. Villa, who’d meanwhile been exiled to the US on a falsified charge, returns to lead his people into a fury once more, getting revenge on Pascal, and to finally make Mexico a real, honest democracy.

A quick side note: it bears special mention that the Fay Wray subplot is on another level. Her character, Teresa, is the sister of a revolutionary-backing major domo who sees Villa as a hero until he returns from exile and brings with him the threat of land reform. But in the spirit of pre-Code bad girls, she loves him for his brutishness and is recklessly turned on by his low-class manners. This would normally be the recipe for a humdrum love connection, but instead leads us to a scene where Teresa first shoots Pancho and then taunts him.

This is after he’s returned from exile and is experiencing his last doubts as a real leader of men. In a fit of emasculated rage, Pancho savagely beats her with a whip (don’t worry, it’s in shadow, lest this be any more gruesome than it is). She laughs wildly and continues to mock his upbringing, insulting him and his father– who the audience saw beaten in much the same way at the beginning of the film. However, that beating lacks the erotic charge of this one, which showcases Teresa’s erotic response to being socially superior even while being physically degraded. Gunfire is soon again exchanged, and Teresa’s death becomes the linchpin for the final act– a demarcation for Pancho between being the hero of all Mexico and instead fulfilling his real destiny as the rightful hero of the lower class.

But it’s so fucking weird.

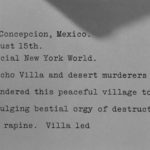

Now, let’s immediately take for granted that this film is 99% fiction. The Mexican Revolution this film portrays hadn’t passed the 15th anniversary of its finish when Viva Villa! was released, so it’s doubtful that the truth was paved over out of a belief in the audience’s ignorance. For a movie that very much advocates the power of the press to balance the power of countries and rewrite national narratives, it’s a film that screams loudly the believe in printing the legend over the truth.

Of course, this version of the legend does come heavily from American perceptions of Mexico, which seems to be rather timeless. Beery’s portrayal of Pancho plays into American preconceptions about Mexicans being lecherous, drunken buffoons as much as American’s own conceptions of themselves– the film’s American reporter is wry, loyal, and more than a little superior to everything that unwinds. But Beery’s take on Pancho is honest and pragmatic, and those two qualities are what make him the film’s hero in spite of his many flaws. He’s constantly evolving towards the right thing, or at least what this film sees as the right thing.

In spite of the stereotypes built into Pancho’s portrayal, Viva is a solid film. It’s a movie clearly of it’s time, so much so that it’s important to note: Viva Villa! was the highest grossing film of 1934. And this wasn’t a cheap film– three directors, footage lost, actors replaced (all this explained below in Trivia). Why did this story connect so strongly?

It promises the audience a certain amount of boisterous cheer and illicit thrills on a great scale, but that can be said about a number of its contemporaries. But, on top of that, it promises a certain degree of hope. After the social upheaval caused by the beginning of the Great Depression, the idea of a dictatorship in the United States wasn’t far from the realm of possibility. Americans saw strongmen like Mussolini as a possible cure for their societal ills, and Viva‘s Pancho is just that kind of righteous leader who would take no prisoners (and, here, literally) to unselfishly save his country from the land-grubbing, money-having jackals.

The movie shows the rise of a deified democracy soon contrived to downfall by craven elites. By film’s end, a plucky, man-of-the-earth, has returned law and order back to the people. He has united the poor (“The poor always was the beasts. Only this time they’re not frightened. Somebody else is frightened, eh?”), subdued the rich, peacefully redistributed the land, and resigned his position once he knew his orders would be respected. The Pancho Villa here is the benevolent dictator myth that got so much traction in the 1930s. It didn’t work out well, but that lesson was yet to be painfully learned.

Today, in a much different world, it’s not much of a surprise that this film creates some of the reactions it does. From its easily derided star, to the rewriting of history, to this film’s salacious back story, this movie has something to offend everyone of a modern stripe. But as long as you can accept the fact that this movie is an import from an alternate universe where Mexican stereotypes aren’t challenged and the only hope for sanity in the world is a humble man with a big stick, you’re fine. And it’s perfectly understandable if you can’t.

Screencap Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- This is a movie whose production is just as colorful as the film, if not more so. Much of the filming was done on location in Mexico, which led to conflicts between Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and the Mexican government, who weren’t happy with the film’s portrayal of Pancho Villa. The film was originally helmed by Howard Hawks and had Lee Tracy in the Stuart Erwin role. (And, let’s be honest, Tracy would have brought an extra layer of smug self-satisfaction and double intent that Erwin’s more playful persona just doesn’t radiate). Due to an ‘incident’ with Tracy– more on that below– Mayer fired Tracy from the film. Rumor has it that Hawks disagreed with the decision so violently that he belted Mayer before being fired off the film as well. (It may also have been that Mayer didn’t like Hawks’ shooting pace and Hawks walked off peacefully, but, hey, we’re in a ‘print the legend’ mentality today.) Meanwhile, tens of thousands of dollars of footage were lost in a plane crash, and William Wellman had to step in to direct until Jack Conway took over to finish production. You can read the full story of the film’s production history over at TCMDB.

Historical accuracy was seldom a priority with this type of film, but producer David O. Selznick (who called Viva Villa! one of his favorite pictures) tried to balance out the theatrics with at least partial authenticity. The movie was shot mostly in Mexico, adding thousands of dollars to its budget. Some alterations to the original screenplay were also made after it was negatively assessed by both the Mexican government and Villa’s widow. Still, Wallace Beery’s performance as Villa is so extravagant, it nearly overwhelms any sense of reality.

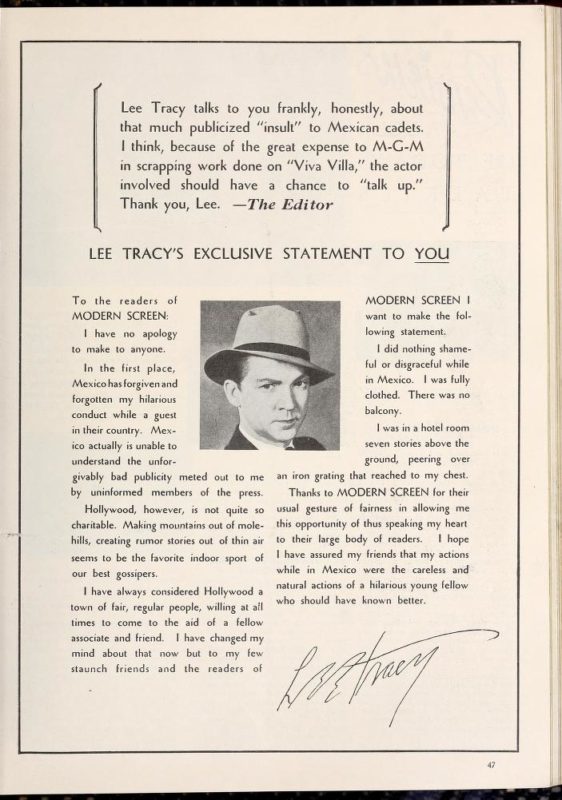

- Viva Villa marked the end of Lee Tracy’s time at Metro. The motor-mouthed actor got involved in an ‘incident’ that has since snowballed into a legend. During one day on location, Tracy and Beery were staying in a hotel. There was a march of military cadets out front. During this time, the legend goes that Tracy, heavily intoxicated and nude, came out onto the balcony and urinated on the parade. This caused an uproar, as I’m sure you can imagine. That may be the embellished version, though– most accounts from the time indicate the truth is more akin to Tracy having a playful exchange of dirty hand gestures with the marching cadets, and the lewdness of that helped craft that legend we know and love.I’ve never read this blog before so I can’t verify the veracity of some of the quotes, but ImagineMDD does a deep dive into what happened and the aftermath. To help try and save his career, Tracy penned a plea for a full page in the February 1934 issue of Modern Screen to try and set the record straight. (Side note: I hope I never ever have to blast loudly in an industry publication the sentence “I was fully clothed” no matter what the context.)

- As mentioned up above, this film’s connection to history is completely minimal. Here’s TCMDB again on who Villa really was.

According to biographical sources, sixteen-year-old Doroteo Arango killed a man for molesting his younger sister and took refuge in the mountains, eventually changing his name to Francisco “Pancho” Villa. In 1910, while he was working as a bandit and part-time laborer, Villa was persuaded to participate in the Madero revolution against President Porfirio Diaz. After Madero became president, Villa, still a member of the irregular army, was condemned to death for insubordination by General Victoriano Huerta. Although the execution was stayed by Madero, Villa remained in prison until escaping to the United States in November 1912. After Madero was assassinated, Villa returned to Mexico and joined forces with Venustiano Carranza to defeat Huerta. Mutual distrust divided Villa and Carranza, who took over as president in 1914, and the civil war continued until late 1915. In early 1916, as a show of power, Villa executed sixteen U.S. citizens in Santa Isabel in northern Mexico and attacked Columbus, NM. Woodrow Wilson then ordered General John J. Pershing to lead an expedition into Mexico to capture Villa, but Pershing’s efforts were unsuccessful. By 1920, after years of continued armed insurgency, Villa agreed to “retire” from politics and was given a ranch in Durango. Villa was assassinated on July 20, 1923 in Parral, Chihuahua. The Hollywood Reporter review notes that the character of General Pascal was “more than a little suggestive” of Huerta.

- The great History On Film goes deeper into comparing the film to the reality, stating in with no uncertainty that the movie has hardly any connection to who Villa really was or how the revolution really went down. Some other interesting notes;

The script does deserve credit for keeping Villa’s comment that “this is a pretty small medal to give someone who did the things that you said I did.”

The screen Villa is killed by a rich landowner seeking revenge. While Villa was assassinated near a butcher shop, the script neglects the massive paranoia that made it almost impossible to get near enough to kill him. Having made many, many enemies during the revolution, Villa’s security depended on the numerous former villistas who had settled on either his hacienda or nearby estates, while the hacienda was turned into a fortress, where the number of visitors was regulated and closely watched. Despite these considerable precautions, he never slept in the same place twice, never allowed anyone to stand next to him, and was always surrounded by fifty bodyguards.

One of my favorite shots in the film is Villa finally assuming the reigns of the country and sitting in the chairs of authority, quietly feeling them and the weight that comes with so much power. Beery may not be much for subtlety, but this scene really helps humanize the wild eyed bandit of the film.

- It’s not often I read Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times sounding incredulous, but I think he thought the Fay Wray stuff was pretty wild, too.

It is for the most part a fast, furious and compelling tale, but there are a few episodes which might very well have been excluded. It is to be presumed that the producers—Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer—had insufficient confidence in Villa as he was as a big drawing card to the box office and therefore they included examples of brutality that are by no means helpful to the production. […] At the close the redoubtable idol of the peons, killer and marauder is himself sent to his death by a bullet from an avenger, but before he breathes his last he knows that Johnny Sykes is going to give him a fine send-off in his Gringo newspaper. So that’s something.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- Now, believe it or not, this film was nominated for Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Assistant Director, and Best Sound Recording at the Oscars. It won for Best Assistant Director– not surprising considering all the extras the poor man had to wrangle.

- The highest grossing film of 1934. No, really.

More Pre-Code to Explore

9 Comments

Anthiny Crnkovich · June 25, 2017 at 5:27 am

The horsewhipping of Fay Wray was cut when the production Code went into effect soon after the film was released. For years, that’s the version seen on television and later on VHS. It wasn’t until relatively recently that this scene and a few other snippets were restored, and the film is now available pristine and intact from WB Archive.

I consider VIVA VILLA among the best of Hollywood’s biopics. Beery carries the film in what is arguably his finest performance, and the rest of the cast scores high points as well. It’s got a sweeping pace with superb handling of the epic-scale action sequences. James Wong Howe’s cinematography is top notch as usual. Although it takes some liberties with its subject, I think the film nonetheless conveys the spirit that fuels any political revolution. At its heart, VIVA VILLA is a passionate, rousing tribute to one of Mexico’s most colorful figures.

thestarlightstudiosbcglobal.net · June 25, 2017 at 1:47 pm

Did you view the uncensored version? Did it have the complete whipping scene? Did it include the scene where Villa crawls on his knees? Where he steals a sandwich from the free lunch in a bar? These scenes were in the 16mm prints shown on local TV in the ’50s and ’60s. But there was also a version that had been censored to placate Villa’s daughter. An M-G-M censor told me this. And that version was the source for the VHS, cable, and DVD versions of the ’80s and beyond. Please let us know what you saw and where. – Mark A. Vieira

thestarlightstudiosbcglobal.net · June 25, 2017 at 1:51 pm

I forgot to mention that in June 1976 (after a portrait session), Katherine DeMille told me about the Tracy incident, but not in detail. She did say that a plane returning to Los Angeles with exposed negative “exploded” in flight. She believed that the plane was actually shot down in reprisal for the Tracy incident. _ Mark A. Vieira

rift · June 26, 2017 at 6:54 am

I picked up this Warner Archive DVD release earlier this year and just moved it to the top of my “to watch queue”. If I have estimate of the times of the Whipping and Sandwich scenes in question I’ll check to see if they are present.

rift · June 27, 2017 at 11:17 am

Mark – love your book:

Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood

A fixture on my coffee table for nearly 10 years

rift · June 27, 2017 at 11:25 am

Regarding the Whipping scene – from an Amazon reviewer, so not sure how accurate but it is encouraging:

“Warner Archive’s DVD-R of VIVA VILLA! was transferred from a pristine 35mm print…The film came out in 1934, the year the Production Code was enforced, and this necessitated several cuts upon its release which are all restored on this disc. Most notable among these scenes is the one of Wallace Beery whipping Fay Wray after she shoots him. Now fully intact, the sequence plays out much better in its surprisingly sadistic tone. The original theatrical trailer is included as a welcome bonus.”

Anthony Crnkovich · June 27, 2017 at 9:19 pm

That is actually from my Amazon review after viewing the WB Archive DVD. As I stated, the scene is intact. After Teresa shoots Villa, he slaps her and she falls,across the couch. She smiles with an erotic glint and taunts him about how her people enjoyed hearing the Peones scream as they were tortured. Enraged, Villa takes a whip and starts beating her, “Scream! Scream!” he yells, as she laughs with what can only be described as sado-masochistic delight. The whipping is shown in shadow against a wall but is nonetheless pretty strong stuff. It also reveals the otherwise refined, aristocratic Teresa as having a repressed, kinky urge.

thestarlightstudiosbcglobal.net · June 27, 2017 at 1:48 pm

Thank you. I’m pitching an expanded version to publishers.

thestarlightstudiosbcglobal.net · June 27, 2017 at 9:55 pm

The cuts in Viva Villa! were not made because of the Production Code, either for the first release or for reissues. In 1971 the retired film editor Chester W. Schaeffer told me that Pancho Villa’s daughter was given a private screening of the film prior to its initial release. But … she was shown a work print that had most of these scenes deleted. She approved it. Then the film was released as we have seen it, with the scenes of violence and Villa’s humiliation intact. Complaints came from Mexico after the film had premiered in Los Angeles, so the negative was quickly cut and new prints were made before the film was shown in Mexico. This was a political issue, not a Code issue.

Comments are closed.