|

|

|

| Johnny Joel McCrea |

Luana Dolores del Rio |

Mac John Halliday |

| Released by RKO | Directed by King Vidor Run time: 82 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- “What is this place?”

“Probably one of the Virgin Islands.”

“I hope not!”

- There are a couple of South Seas orgies. Ya know.

- There’s a nude moonlight swim. Well, I mean, they’re wearing things if you squint a bit, but we’re clearly invited not to take that next step.

- The two lovers enjoy a bit of struggle in their foreplay.

- Joel McCrea rubs himself with dark paint so that he blends in with the natives. Yeah.

- A woman is beaten and whipped.

- On an island by themselves, McCrea promises to build them a place to sleep. She giggles excitedly, and he smiles, “and, oh yeah, that too!”

Bird of Paradise: A Woman’s Place is in the Volcano

“I happy, Johnny. I happy you steal me away and we live together. I happy you teach me kiss. I happy you hold me. I happy for everything. It was best thing that ever come to me!”

There is little to recommend in Bird of Paradise outside of sex. Steamy, erotic sex. Not explicit, of course, but that enticing kind that clouds your mind on idle afternoons when you drift back to days filled with teenage hormones. And who could possibly want that from a film?

Joel McCrea’s Johnny and a host of rich white guys show up on a remote South Seas island for a bit of adventuring and exploring. What they discover is one of those virginal, magical tribes that’s really into free love and endless partying, and are a-okay with some white dudes sitting on the fringes. The conflict comes when Johnny becomes particularly enticed with del Rio’s Luana, the king’s daughter. That’s taboo (no, not Tabu), but Johnny sticks around on the island while his friends depart for more yachting; they promise to swing around and grab him whenever ‘going native’ gets old.

While the natives tolerate him at first, especially his mysterious ukulele, his pursuit of Luana puts him on the outs. As the king’s daughter, she’s not only slated for marriage to another chieftan, but as the first in line to be thrown into the volcano in case it begins to smoke. The two run away together and hide for a while, with Luana even picking up a little pidgin English and Johnny putting together a cottage that would put the Professor to shame.

But in the movie, as in life, eventually that volcano has gotta blow. Luana is kidnapped and prepared for sacrifice, and Johnny rushes in to save her. There’s a fight and blood and even a few gunshots for effect. Do the lovers end up together? Despite the proliferation of eager-eyed sex, no, Hollywood was still too gun shy to put a handsome white college boy in a New York bungalow with an exotic beauty. No, no Luana learning how to operate a toaster, just as there’s no way Johnny is going to fit in as a volcano worshipper.

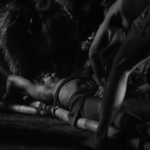

Few movies in the pre-Code era are so blatantly about how exciting and joyous the act of copulation can be. The moonlight swim that seals the deal between the two main characters is enticing, shot with shadows to leave the audience’s imagination whirling. The two tease and chase, with wisps of clothing flying furiously. Sweaty bodies, long meaningful looks, and the two kindly taking turns pinning each other down.

It helps that the movie buys into this pulp-magazine-cover fantasy. The film was shot alternatively between Catalina Island and some of the same backlot sets McCrea would soon be galloping on for The Most Dangerous Game at RKO. It looks lush, with Busby Berkeley coordinating the native’s dancing, and Max Steiner’s score giving the film an oddly operatic tone. Director King Vidor’s camera work is careful, with bursts of energy to match the lovers as they dart about.

All of that said, there’s not a whole lot to the film besides how two sweaty bodies can overcome just about any non-fiery obstacle. Sex, indeed, is the universal language. It’s kind of impressive how much del Rio gets across without speaking a word of English until well past the halfway point. That’s around where she shows up with just a grass skirt on and a pair of leis covering her breasts, making them the only thing keeping censors from blowing their lids, and the male audience from doing the same.

Del Rio’s work is kind of impressive since Luana’s desires for sexual freedom while still steadfastly sticking to the culture and religion she grew up with give her a conflicted conscience. Here, she’s the tragic figure who’s devotion dooms her; McCrea is the dopey pretty boy who doesn’t think things through. While there’s a lot that can be said about this film’s downbeat take on miscegenation, it doesn’t ridicule Luana’s belief in the righteousness of her choice. It’s a downbeat women’s picture ending with religious undertones, no matter how much we, the white audience, presumably know better.

Outside of the sex, the movie is pretty emotionally sparse. The natives are treated as disposable at best. The others on McCrea’s yacht include Skeets Gallagher and Bert Roach making terrible regressive jokes, while John Halliday is along to be the voice of mild reason. This is a movie that requires the audience to turn it’s brain off and go with the flow.

This film feeds into the Blue Lagoon fantasy that endures, that any tropical island with two nubile, willing people is a paradise. Bird of Paradise is both emblematic of its time as well as daring– sex sells, and the native girl getting it in the end keeps people from losing their minds. It’s a gem of style over anything resembling substance.

Gallery

Click to enlarge. All of my images are taken by me– please feel free to reuse with credit!

Trivia & Links

- Apparently this is Lon Chaney Jr.’s first film– though I missed him. :/

- Remade in 1951 under the same title with Debra Paget and Louis Jordan.

- The New York Times’ Mordaunt Hall calls Luana “fascinating” but sees the picture as only “moderately interesting”.

- The always-worth-reading Glenn Erickson dissects why the film was controversial, as well as why the pendulum has swung and now it’s viewed as racist:

The real sex in Bird of Paradise is a matter of attitude. Luana is assertive and direct in her sexuality, and still feminine as all get-out. The idea of being attuned to nature is not a joke — this young princess knows she’s in bloom, and has maybe fifteen years before she becomes fat like most of the older women of her tribe. Bird of Paradise communicates the urgency of love.

The superstitious curse that pulls Luana and Johnny apart is mostly invented, yet says more about the way western drama structures its adventures among natives of color, any color. It’s okay for Johnny to sow some wild oats in the islands, but Luana isn’t for him. He can’t take her home to his uptight family, after all. Johnny may be willing to defy the rules but Luana is not — she fervently believes that her people need her more. The ugliness of the concept enters when it is assumed that the native culture offers savage and unjust solutions for problems, like sacrificing women to volcanoes. (Well, primitive cultures aren’t all that more fair to women than we are, I guess.) It’s just that too many classics of western fiction and dramaturgy find an easy solution to an inconvenient relationship by killing off the ‘dark’ woman, to allow the hero to return to his own kind back in civilization. Bird of Paradise at least has the decency to keep Johnny’s “proper” mate off-screen. We’re also supposed to accept the idea that the natives will allow the whites to shoot down their medicine man and the jilted prince, and not ambush the yacht at the first opportunity.

- Margarita Landazuri at TCM has loads on the background of this production. I mentioned some of it up above, but here’s how it starts:

When David O. Selznick became head of production at the troubled RKO Studios in late 1931, one of the properties he inherited from his predecessor was an out of fashion play, The Bird of Paradise (1912), about a doomed interracial romance between a young American and a Polynesian beauty. The play, which made legendary stage actress Laurette Taylor a star, had been a success in its day, and had helped popularize Hawaiian music and culture. Selznick invited one of M-G-M’s top directors, King Vidor, to read the play and consider directing a film version for RKO as a vehicle for Mexican actress Dolores del Rio. Vidor began reading the play, but couldn’t get through it. He told Selznick it would make a terrible film and he wasn’t interested. Selznick, who hadn’t read the play either, was undeterred. He told Vidor, “Just give me three wonderful love scenes…I don’t care what story you use so long as you call it Bird of Paradise and del Rio jumps into the volcano at the end.” Attracted by the freedom, and the chance to portray the ethnographic details of Polynesian culture (his first talkie, 1929’s Hallelujah! had explored the lives of Southern blacks), Vidor agreed.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is in the public domain, so you can catch it on YouTube or buy it on DVD or even pick up a blu-ray.

More Pre-Code to Explore

1 Comment

Terence · January 16, 2017 at 11:05 am

An interesting comparison would be Never The Twain Shall Meet (1931) where the exotic island girl, played in a rather moronic fashion by Conchita Montenegro, actually does meet the uptight family. When the family disapproves, her WASP boyfriend Leslie Howard briefly goes native, only to become morose when she has more than one partner. Hollywood in that era really couldn’t handle miscegenation.

Comments are closed.