Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- I’m going to have to stretch it a little this week, since there’s inherently very little about this picture that was risque for the time that it arrived in. There’s a cute Indian girl who runs around with a cute little white boy and forty years later they have cute little kids running around together. That may not sound too exciting today, but that’s almost racy 80 years ago.

- The gambling hall that our hero gives his big religious speech has several painting lining the walls of women in fascinating poses and few pieces of clothing.

The Particulars of the Picture

|

|

|

| Yancey … Richard Dix |

Sabra … Irene Dunn |

Dixie Lee … Estelle Taylor |

|

|

|

| Isiah … Eugene Jackson |

Jesse … Roscoe Ates |

Tracy … Edna May Oliver |

Cimarron: Civilizing Those Who Need It

Fate. Civilization. Great men doing great things and dying in the dust, alone and forgotten.

Cimarron is that sort of story, the one where the world is big and scary and it’s up to good men to tame it. Back in the day ‘civilization’ was equated to cars and roads and people not shooting each other, and while we seem to be rolling back those lofty expectations of ourselves, Cimarron reminds that once our roads were nothing but dirt and our cars horses.

It also reminds us that some movies can say a lot about the American condition while being ragingly boring, offensive, and borderline schizophrenic. There’s few things to love about Cimarron, but plenty for a modern audience to simply gape at. Of the the many movies of the early 1930’s that I’ve watched, this is probably the closest I’ve seen to deserving to be a museum piece, stuck in a dusty corner somewhere for people to crane their necks at then hurriedly move along.

Yancey and Sabra Cravat: Too Smug to Fail

The film starts in 1890, where the Oklahoma Land Rush is getting ready to kick off. We meet Yancey (Richard Dix), a man from Kansas who is eager to try his hand at this new frontier. There’s also Dixie Lee (Estelle Taylor), a woman who is after the same parcel that he is. The Rush begins, and through some minor measure of feminine trickery, Dixie gets her way and Yancey is left to go back to Kansas City empty handed.

He’s still bound and determined to go back to Oklahoma and make a name for himself, though. Bucking his wife’s controlling family, he gets a pair of wagons and takes his wife, Sabra (Irene Dunn) and young son Cimarron and heads to the newly founded town of Osage. He decides to do the noble thing and open a newspaper, the Oklahoma Wigwam. Well, maybe the name isn’t that noble, but the idea of doing it sure is!

There’s a lot that’s been said about the film’s opening sequence, where thousands of extras arrived to reenact the Oklahoma Land Rush, but scant mention of how impressively stocked Osage is. Anyone who has seen a Western with its almost deserted towns will be impressed by the amount of bustling city life we get to see here, making it one of the liveliest frontier towns ever depicted on the screen.

Osage in the beginning.

The film then follows the city of Osage from its earliest days to the then-present 1930’s, showing in a microcosm how much the world had evolved for these people in 40 years. To do this would seem to necessitate a large cast of wacky characters to populate it. Unfortunately, this also becomes where the movie’s message starts becoming obvious, which is ‘tolerance’ in the most backwards way possible.

The racial politics of Cimarron are, for modern audiences, to be polite, mind boggling. It’s a weird mix of liberalism and stereotypes, indulging its audiences to cheap single note characters while also begging for everyone to empathize and understand them.

For example, Isiah (Eugene Jackson) is a black servant boy that we first see hanging off a beam in the ceiling, fanning Yancey’s extended family. He sneaks along with them as they make their way to the new territory, and works as a house boy for them. While this boldness is certainly nice, every single other thing Isiah does is treated as a massive joke.

How embarrassed have you felt today?

Their arrival in Osage sees him go absolutely nuts… when he sees a cart selling watermelons. He wants to go with the family to church… but he wears an oversized set of dress clothes, and the entire town laughs at him. He remains oblivious, which only makes the ridicule sting that much more. It’s like the scene in Whoopee! where a woman freaks out at a black man touching her, only with less hatred and more outright condescension.

There’s also a Jewish man named Chico, who starts out as a lowly merchant and soon becomes a trusted friend and employee of Yancey. He is quiet and deferential, and Yancey stands up for him to several unsavory bandit types who push him around.

This is one of many instances in the film where Yancey’s duty is that of protector, and, in fact, that seems to be his main role in the film. He stands up for the little guy, black, white, Indian, or someone with a particular disability to their credit.

Yes, this is the Jewish guy after he’s attacked by some bandits. Very subtle, movie.

His actions throughout the film seem to closely align with the idea of the “white man’s burden”, where it is the duty of white men to help civilize other races and cultures so that they may become equal to their own. Nowadays this doctrine is usually viewed as “condescending as all hell”, which is why so much of the movie stings.

This is especially true in its treatment of Native Americans, an area where many Westerns falter. Yancey’s character, an eager adventurer with a sense of pride as big as the land, oscillates between genuine sympathy, condescension, and outright hostility towards Indians. This sometimes occurs across the same scene, such as one where he lambasts Oklahoma for opening up further Indian territories for settlement in his newspaper before greedily talking to his wife about his desire to claim some of that land for himself.

It helps that the movie makes Sabra far more of a hardline racist than Yancey. She gets moments where she throws a fit when Yancey dares insinuate that Indians should be treated equally under the law, or when she nearly melts down when she learns that young Cimarron has developed a crush on a young Indian princess who sometimes hangs around the house. She learns over time how right her husband is, and the film’s coda addresses that, though, like most of the movie, it comes as a condescending pat on the head.

“Darling, let’s be condescending together.”

That brings me to another weak point of the film: Irenne Dunn’s acting spends most of Cimarron somewhere between manic and restrained, or as most of us would recognize it: insanity. Dunn has never been a favorite actress, and while she certainly has decades of a character to work with here, she’s far too hamstrung by the film’s gender politics to churn out anyone worth giving a damn about.

Yancey’s (and the film’s) spirit towards the fairer gender also rarely aligns with common sense. Women are all crazy and irrational until good ol’ Yancey teaches them a lesson. This is especially true in the case of Dixie Lee, who squanders the land she stole from Yancey and becomes the local town Madame. Sabra and the other ladies of society detest her, and leap at the opportunity to prosecute her for adultery. Yancey, in his benevolence, steps in and pleads Dixie’s case, outlining how she is being judged for her duties and not her guilt. Sabra learns that she was being foolish and, like all other things Yancey does or says, she soon comes around to his way. The right way.

Dixie Lee proves once again that prostitutes were instrumental in the old West, even ones not named ‘Miss Kitty’.

If I seem to conflate the film’s viewpoint and Yancey’s, it’s because they rarely seem to diverge. If the last ten minutes of the movie were Yancey simply fantasizing about what the future held, it’s believable to say that they would be identical.

That Yancey becomes this righteous force is more than a bit grating, especially since so many of the film’s themes seem to be to revisit the Western as a whole and show how its change eventually forced out men like Yancey and others like him who formed the West. Yes, it’s revisionist in its own way, predating works like Once Upon a Time in the West and Unforgiven in telling of their places where some men are left behind the times no matter how good they may be.

The film illustrates this deftly with the character of The Kid (yes, The Kid), who was once a cowboy friend of Yancey’s. They worked as ranchers, but took divergent paths: Yancey settled down, and The Kid became one of those frontier bandits you’ve probably heard so much about.

And Osage grows a bit bigger.

Later, when The Kid shows up in town and Yancey has no choice (nor much resistance) to gunning him down, the movie makes its historical stance clear: Oklahoma was the last breath of the Wild West, and with civilization died the last of its myths. The Kid and all of the other characters like him couldn’t survive in the new world, and Yancey, while being the hero, is so consumed by his own sense of white male heroism, completely overlooks his own behaviors, eager to rush home and start chiseling in another notch in his gun. He’s a man who is doomed to also belong to this era, as we will soon see.

I want to talk about the end a bit, so skip to after the picture of the statue if you don’t want to read any spoilers.

The film ends in the present day, with Osage a booming town thanks to the oil industry. Yancey, who has periodically run off throughout the film to pursue his dreams and return home to his worried family and adoring friends, has disappeared yet again. Sabra’s leadership of the Oklahoma Wigwam has led the paper to becoming an institution, though Yancey’s name still appears as the editor and proprietor.

That’s so Yancey.

In fact, Sabra has been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She’s making her preparations to join, and gives a magnanimous speech bringing together the cast in a spate of old age makeup. Her daughter has matured, her son has married that Indian princess, and the Indian princess gives a speech that, like most of the film’s depiction of minorities, is cringe worthy.

Sabra’s lengthy speech ends and she goes down to some nearby oil fields for a tour. When one man is injured mortally saving some drillers from an faulty explosive device, Sabra recognizes the name and the sense of heroism. She clutches Yancey, an old forgotten man who had one last act of bravery within him. He dies, clutched to her bosom.

I mentioned before that Yancey’s end is exactly the one he would have wished for himself, and that’s what I mean here– a noble death, as a common man, and with everyone recalling what a damn swell guy he was. This reveals both his and the movie’s view of heroism, which isn’t simply a noble death, but a loud, noisy one. The last shot of the movie is the revelation of a memorial to Oklahoma’s pioneer forefathers, and it’s heavily implied that that’s a statue of Yancey himself; the noble wonderful few who made such a difference. It’s so over the top vainglorious that it only hammers home just how dated the movie is in so many regards.

That’s even more so Yancey.

Cimarron is an epic, running 120 minutes (nearly double the going rate of most Pre-Code films) and boasting one of the highest budgets of a motion picture at the time. A lot of other reviewers of this picture seem to simply regard the Academy’s fondness for expansive epics for its win for Best Picture of 1931, and it’s certainly a factor. The Academy is also fond of big flops, which Cimarron was in spades, though the sets constructed for this movie served the studio well for years to come.

But I think there’s a further reason for its popularity with critics can be traced from Mordaunt Hall’s original review for the Times. The man enthuses about the film’s timeline and scope, and is bowled over by Dix’s acting. Now, Mordaunt and I have our differences in film opinions, but I actually see where he’s going with this. What most of us bloggers or critics in the 21st century see is an old relic of a film about a world now 130 years removed.

In the 1930’s, though, this was simply seeing the last forty years treated as an epic. A testament to how much things had changed in a handful of decades, while tracing out a future where equality and prosperity are guaranteed for people oppressed only so long ago. This picture isn’t simply epic in its scope when we discuss the extras or the budget, but its vision of progress and the generosity of great men was something that any audience member could have felt a deep sympathy with.

Osage today. Today 1930, I mean.

That’s why I think, as a macro piece of work, Cimarron isn’t bad. And watching Oklahoma go from a simple line on the prairie composed of eager men and women on one spring afternoon to a familiar city is fascinating, even if every single humanizing story seems to fall flat on its face.

Oh, and its view of racial harmony has become completely detestable. And the film’s writing consists of massive chunks of exposition that often just leaves the viewer confused. Oh, and the film’s comic relief is so bad the director keeps cutting him off. Look, if you’re a completest, for Westerns or Oscars, Cimarron is probably worth experiencing once. I’d skip it otherwise.

Gallery

Here are some extra screenshots I took. Click on any picture to enlarge!

Trivia & Links

- The main reason anyone probably seeks out Cimarron any more is that it won Best Picture for 1931 at the Oscars. It’s also widely considered one of the worse, for reasons I hope I outlined above.

- Actual line from the movie: “Shakespeare! Nyaaaaaaah!” No further information necessary.

- James Bernadelli over at Reelviews goes through a full rundown of the film, from its origins to its stars and final place in history. I disagree about it being more soap opera than Western, but most critics seem to enjoy pretending that revisionist and postmodern films just started last year.

- Jerry’s Armchair Oscars tear this one apart, though they inexplicably think that Chaplin’s City Lights (a picture that makes Cimarron look like Unforgiven) is a good substitution. I don’t agree, but it’s a good read.

- Since this was a Best Picture Winner, plenty of blogs have stepped up to give their takes on it. FilmFanatic has some good info, DVD Dizzy is critical, and JWR enjoys it in its own way.

- The inimitable Pauline Kael reviewed this one. She was not a fan.

- This is the only picture in its illustrious history that RKO Studios ever produced themselves to win Best Picture.

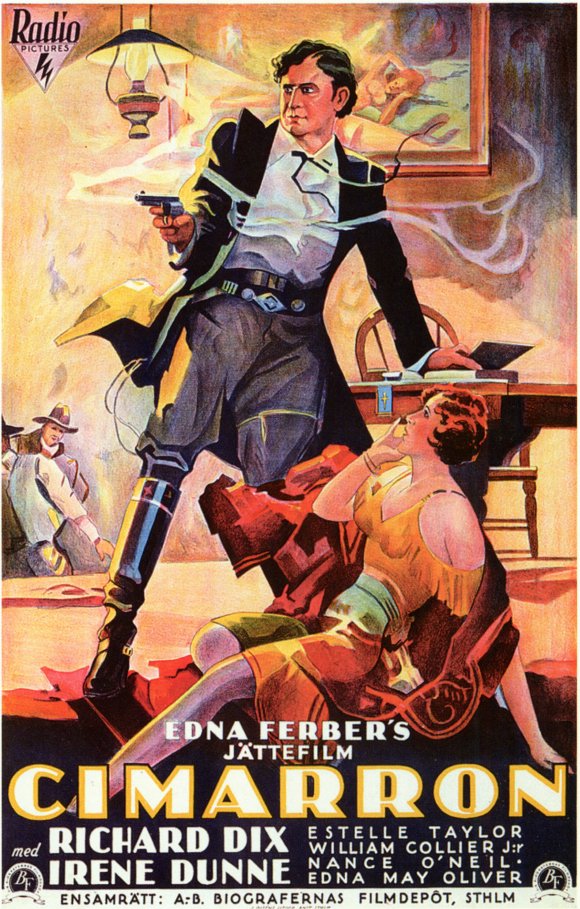

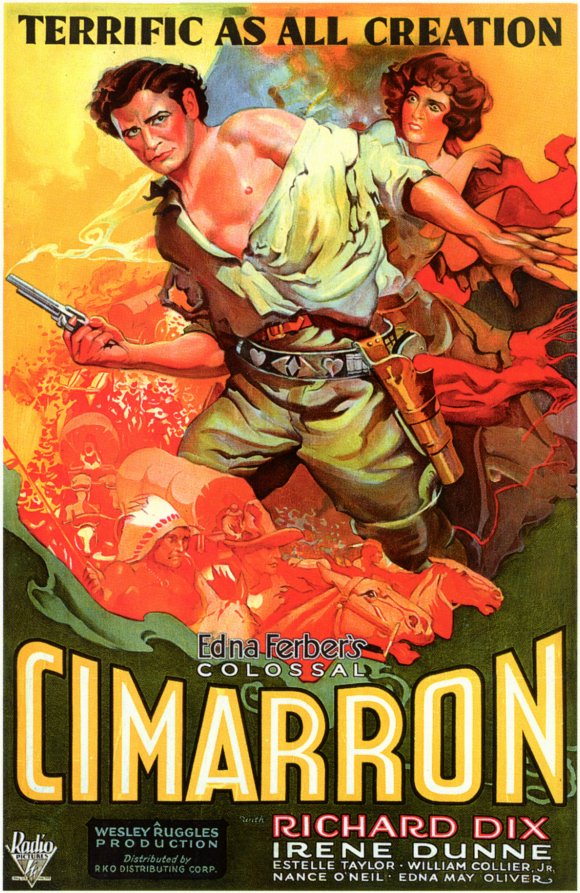

- Man, these posters:

Haha, check out the painting behind Dix’s head. This is a vague approximation of a scene from the film, but some scrappy painter was probably pretty happy to get to sneak that in.

Richard Dix’s nipple may or may not be included in the final film.

Availability

- This film is available on Amazon, and can be rented from Classicflix.

5 Comments

shadowsandsatin · May 19, 2014 at 10:53 pm

I loved your write-up, Danny — I’m actually kinda fond of this movie, because it’s just so ridiculous. Everything about it — the performances, especially Dix and Dunne, the plot, the unbelievable racial stuff, the you’ve-got-to-be-kidding-me ending — it’s just a treasure. I may watch it again tonight.

Danny · May 20, 2014 at 8:01 pm

In the time since writing this review I did end up reading Edna Ferber’s So Big! (mostly on the basis of the Stanwyck movie of the same title). Ferber also wrote Cimarron, and I think that showed me just how much better Cimarron must read because she’s a hell of a writer, and the book version of So Big was much tighter with the thematic material than the movie (which I still love). I may end up reading Cimarron and revisiting it at some point– there’s some great ideas here, I just wish the movie wasn’t so goofy on the whole.

Eric · July 26, 2014 at 1:42 pm

Hi Danny. I just saw this film today for the first time. I’m indeed one of those completists and bloggers you mention, as I made it my goal in 2014 (thanks in great part to my wife) to see every Best Picture and blog about them for my three or four regular readers. Prior to starting the blog series I’d probably seen about half of the 85 (now 86) winners. Some of the films I hadn’t seen before doing so for the blog, at times I feel like I may miss some plot points, so after viewing the movie I check around the internet for several synopses and reviews of the film to fill in any blanks within the story I may have oversighted. Is that even a word? My spell check just spit at me. Whatever, it should be a word because the context makes sense to me in that sentence. At any rate, checking synopses and reviews at one point led me here. I found your review tremendously entertaining and I thank your piece here for letting me know that Yancey was initially based in Kansas City, which was indeed something I missed in my notes.

I found myself in agreement with much of what you said here. You used the word “schizophrenic” and I wrote down that word in my own notes while I was watching the film. That’s about the best way to describe this movie. It really isn’t a bad film, but it just goes in so many different directions content-wise that at times you’re marveling at it and other times you’re wondering what in the hell the Academy was smoking in 1931. Still, with that said, I’ve certainly seen worse movies win. “Annie Hall” over “Star Wars”? “The English Patient” over “Fargo”? “You Can’t Take it With You” over “The Adventures of Robin Hood?” Compared to those films, “Cimarron” is stellar.

With your permission, I’d like to include your photo “cimarron15.png” within the extra screenshots gallery above for use in my blog. I took numerous screenshots while watching the movie and it turns out that one of my photos was pretty much exactly that one above, but your shot is ten times clearer than mine is. Notwithstanding the answer to that question, thank you once again for the excellent review. This is a website that’s right up my alley.

Danny · July 28, 2014 at 11:41 am

Oh, yeah, totally, please use the picture. And I’ll disagree with you on Annie Hall over Star Wars, but that’s just because I can’t stand Star Wars for a minute. And thanks for coming by. Good luck with your project!

drush76 · July 14, 2015 at 6:34 am

Eugene Jackson’s son or grandson was in the 1965 film, “SHENANDOAH”. He portrayed a slave who became a Union soldier.

Comments are closed.