|

|

|

| Mabel Joan Blondell |

Barbara Hemmingway Ruby Keeler |

Jimmy Higgins Dick Powell |

|

|

|

| Mathilda Hemmingway Zasu Pitts |

Horace P. Hemmingway Guy Kibbee |

Ezra Ounce Hugh Herbert |

| Released by Warner Brothers | Directed By Ray Enright and Busby Berkeley |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code-ish

- Leading romantic couple Barbara and Jimmy are 13th cousins, or so Jimmy says to calm her worries.

- Sweet Jimmy Higgins puts on a big Broadway show that includes a couple of musical numbers with scantily clad women. More on that below.

- Pokes fun at censorship, right in the ribs. Kibbee can’t even pretend to swear, noting, “I’ve called every… blankity blank drugstore in this town!”

Dames: One Last Bow for Pre-Code Hollywood

“Mr. Ounce does not approve of females.”

Busby Berkeley’s track record in the early 1930s is stellar. The choreographer’s work, combined with the talents of dozens of great directors, can ostensibly be said to have peaked in the stunning Gold Diggers of 1933. That picture was followed by the decadent Wonder Bar and today’s feature, Dames. Released in September of 1934, just a few months after the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code, Dames is a playful rebuke to the encroaching era of stifled morality.

As with Berkeley’s other major early 30s productions, the faces are familiar in front of the camera. Dancin’ Ruby Keeler gets a chance to stomp on a few stage floors, Dick Powell has that big old smile, and Joan Blondell gets to pop up under a few covers where she clearly shouldn’t be, not that anyone in their right minds should be complaining.

Seriously, start complaining. I dare you.

But there’s a weird twist to Dames that throws off a lot of people. While Keeler, Powell, and Blondell all get their moments to shine and their big musical numbers, they’re not the main event of the movie. Dames is actually a showcase for the comedic stylings of Hugh Herbert, Guy Kibbee and Zasu Pitts, three of the goofiest film stars of the time. None of their comedic stylings are escape the general category of ‘broad’, with Herbert as the eccentric buffoon, Kibbee as the portly, bumbling idiot, and Pitts as the fragile oddball.

Herbert’s Ezra Ounce is an kooky millionaire who may as well wear his purple underpants on the outside. He’s bound and determined to use his fortune to help bring decency and morality to New York City, roping in his gold digging relatives Kibbee and Pitts who hope to profit from their partnership by leading up the newly formed Ounce Foundation For the Elevation of American Morals. Or OFFEAM for… short, I guess.

But trouble-making distant relative Jimmy (Powell, here avoiding being a Tommy, Scotty or a Billy this time around) is bound and determined to get his new musical variety show, Sweet and Hot, onto the stage. Since that’s exactly the kind of thing Ezra is against, Jimmy uses out-of-work chorus girl Blondell to blackmail Kibbee’s Horace P. Hemmingway into ponying up the cash to put on the show. Horace keeps under wraps so that Ezra won’t find out and he still has a shot at a fortune once his dear eccentric brother-in-law passes on. Ezra, seeking to send a message to the rest of the New York art scene, puts together a gang of hoodlums in tuxedos to attend the premiere of Sweet and Hot and, with his signal, crash the party.

Subterfuge!

Rotund Horace is more or less the protagonist of the picture, a miniature Sisyphus whose attempts to gain a small fortune out of being a simple toady is confounded at every turn by Blondell’s perky… well, needless to say, more things that a censor would disapprove of. Pitts as his wife is as equally as sexless as Horace, though escapes temptation; she doesn’t even share a bedroom with him. His character is desperate to remain a good Christian eunuch for Ezra’s sake against the perpetual plague of Blondell’s perkiness and fate itself. As Ezra constantly orders him to have his “loins girded for the battle” against sin– probably not the wisest idea to always referring to loins and sins in the same sentence — Horace is also revealed to be ‘the sausage casing king’ of New York and stuck with the middle name of ‘Peter’, just for euphemistic effect. I think his journey here could be pretty well documented in a Dames remake by the Coen Brothers– A Serious Man with singing.

Hugh Herbert is the antagonist, naturally, the moral majority embodied in one eccentric millionaire. But forthright indignation only extends to women. Besides being okay with a narcoleptic bodyguard whose favorite thing to do when he wakes up is to shoot his gun wildly, Herbert’s Ezra suffers from acute nervous indigestion– AKA the hiccups. The only solution that Ezra abides is Dr. Silver’s Golden Elixir, an ancient (pre-Prohibition) medication that just so happens to be composed of more than 50% alcohol. It’s apparently so curative that Kibbee and Pitts begin downing it regularly as well. And it gets even better when the new formula is released, which ups the alcohol percentage to 79%– which makes it something like 160 proof. Yum.

Sounds pretty good, right?

The love triangle that concerns the young and pretty actors, with Blondell’s busty ingenue cleaving apart 13th cousins Powell and Keeler, is perfectly paltry. Blondell’s entire role is simply ‘sexpot’, with her motivations nearly always dictated by a third party. Powell is his usual bundle of crooner smiles, and, while I adore Keeler (and am apparently in the minority in that regard), her part here never rises above that of petulant child with gams to die for. She does manage the most remembered line of the picture, which serves to emphasize her personal lack of personality:

“I’m free, white, and 21. I love to dance, and I’m going to dance!”

So, overall, unless you’re a Kibbee or Herbert fan, Dames probably ain’t your cup of tea. But discussing the plot in a movie filled with Busby Berkeley numbers is fairly futile, as you certainly won’t find this movie in a “Director Ray Enright Collection” any time soon. The film’s last third is set at the theater showcasing Sweet and Hot, and we’re treated to the usual Berkeley extravaganzas for this go-around. First up:

“The Girl at the Ironing Board”

The musical number most rarely mentioned during any discussion of Dames is, weirdly, its most pivotal. A send-up of Victorian morality, “The Girl at the Ironing Board” is a loud, boisterous number that’s completely looney even by Berkeley standards. Rather than focusing on his usual visual geometry, we instead have Joan Blondell dressed up as a turn of the century laundress singing odes to empty long johns.

Don’t worry, the long johns and long underwear come to life and reciprocate their love, with different pairs belting out a few baritone bars. Another sequence sees a herd of laundresses hoist dozens of white shirts upon their heads and use their hands to simulate swans. Blondell feeds them carrot sticks.

It’s hard to see in this .gif, but Blondell also gets smacked with a carrot too. Doesn’t even blink!

It’s dopey. Completely, undeniably silly stuff. Blondell’s anti-singing is the highlight of the piece. It’s such a wide-eyed, raunchy, broad performance of terribly goofy number that sounds purely camp every step of the way. In one special moment, an empty shirt even pinches Blondell on the behind. The invisible man escapes a face slap, this time at least.

But it’s more than that. For a piece that is so clearly rooted in the past, it’s also very much of the then-present. One refrain quotes “Shuffle Off to Buffalo”, the big number in the turning point in Berkeley’s career, 42nd Street. It creates a nice series of bookends for Berkeley’s pre-Code efforts. Another moment has Blondell bust out with this incongruity as she tackles a sleeping gown to the ground:

“So come up and see me sometime!”

don’t mind if i do

Yeah, it’s Mae West’s catch phrase. There’s no doubt that Blondell’s character here is just as sex hungry as her 1930s counterparts, with the message being that even the most ‘clean’ working girls have dirty minds. It’s a funny dichotomy to be sure, especially since it’s presented as a bawdy comedy. Ezra (and presumably the censors of the time or even you the viewer) doesn’t find the number objectionable, even though it’s a boisterous ode to a woman’s sexual fantasy life.

No, you’re not seeing… 32.

“I Only Have Eyes For You”

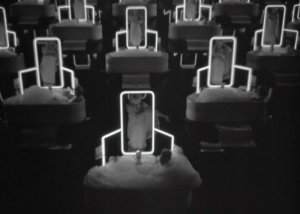

If “The Girl at the Ironing Board” is about how impure even the cleanest women’s thoughts can be, “I Only Have Eyes For You” extrapolates this, taking a man’s idea of traditional romantic love and perverting it, ad infinitum.

The number begins with Dick Powell finishing up his shift at a Broadway theater before taking Keeler out for a night on the town through the busy streets of New York. The two board the subway, and Powell increasing starts seeing Keeler’s face take over advertisements. This expands past mere advertising and into a dream world as a bevy of photos of Keeler’s face subdivide and grow. This then extrapolates into dozens of dancers with identical gowns and haircuts, all letting loose on some of the most purely deco set arrangements on film. The dancers reunite into another visage of Keeler’s face, which then turns into a handheld mirror that reflects back on Powell and Keeler on the subway, napping away.

The number ends with Powell’s only having eyes for that gal leading them into a spot of trouble, as his focus on Keeler (for everyone else “disappears from view”) leads them to nod off on the train and be stuck at the end of the line. He carries her over the train tracks and back to reality as the song ends.

This just looks like fun.

There are many instances of reflections throughout the number. Besides the heavily reflective black floor (check out that screenshot above! it’s like walking on a pond!), the song constantly deconstructs Keeler’s image, breaking her face apart and reforming it, turning into dozens of beautiful women and then back into one perfectly formed face.

This gives you a chance to reflect on Powell’s obsession, which is purely physical. Every woman he sees is Ruby Keeler. If one woman is every woman, does it matter which is which? There’s no doubt that Powell’s obsession fits into the noble ideas of traditional marriage, but the way he fantasizes about it seems to indicate it’s only her physical appearance that he values. And while Keeler is cute, no doubt, there’s little here to indicate that it presupposes a man’s lust as anything more than physical. He only sees her, she is everyone. What is he really in love with?

There’s also one interesting moment here when we see the character that Powell is playing in the number is working at a theater showing The Merchant of Venice. (You can see the sign advertising it in a ‘blink-and-miss-it’ moment). Merchant of Venice is a play that concerns religious conflict that reflects rather handily in the film’s metanarrative (or its narrative about it’s narrative– don’t worry there won’t be a test). Venice‘s play’s central theme is about the distrust between the Christians and Jews, a conflict that was replaying itself in Hollywood at the time. The play’s racial themes also kept it from being filmed during the Golden Age of Hollywood, as it was often interpreted as an anti-Semitic work through most of its history.

Another great moment during the number involves one dancer is walking towards the camera only to step on it– breaking the illusion of where the camera is at for the audience and sending a temporary jolt into the viewer. This is something more than just images connected and unconnected, for it’s breaking the fourth wall for one brief second simply for the sake of illustrating how complete the Berkeley’s singing and dancing puzzle box is by keeping all of the Keeler’s still trapped within. This moment is reflected in a later number “Try to See It My Way”, which has no imaginary walls and contains none of this number’s fantastic illusions. But more on that in a bit.

I have to be completely honest– “I Only Have Eyes For You” has a handful of my favorite shots in all of movies (including that wonderful shot to this paragraph’s left). It’s wildly inventive and playful, a peon to sexual obsession. The many reveals of Ruby Keeler are breathtaking, and the way the film repeats and rearranges is nothing less than visual poetry. Keeler, who must have been a little weirded out seeing the final product, is nonetheless absolutely glowing throughout. Her character loves the adoration, and it sells the love affair so much better than all of the cheesy lyrics that Powell can toss out.

Also, it’s a number that’s also a lot of fun to watch with a significant other and gauge their reaction to. Trust me.

morning!

“Dames”

“Your knees in action, that’s the attraction…”

I’ve read that “Dames” is possibly the most sexist musical number ever put on film and, well, yeah, for the most part. A celebration of the feminine figure and form, it’s essentially an ode to joys of a good looking woman. Not that I think there’s anything spectacularly wrong with that– a thing of beauty is a joy forever, after all– but “Dames” is a bit deeper than the moniker ‘sexist’ would give it credit for. But only by so much.

“Dames” is a small scale replay of a Gold Diggers movie. We start with the enterprising producer (Powell, who warbles out the tune) deciding to put on a show. A bevy of smiling beauties arrive as he puts out the casting call. He ponders, quite correctly:

“Who writes the words and music to all the girly shows? No one cares, and no one knows.”

As we wind our way through the mini-narrative, we get to follow the showgirls and their morning routine. Busby doesn’t dial down the eroticism here as we get to see dozens of women sharing beds together and each getting their turn to primp and bathe. The song continues to muse:

What do you go for, go see a show for?

Tell the truth, you go to see those beautiful dames.

You spend your dough for, bouquets that grow for

All those cute and cunning, young and beautiful dames.

Everyone loves a beautiful woman. Even a blind man is taken aback with appreciation as the girls wind their way to work. Upon arriving, they proceed to enter into the usual Berkeley patterns in negative space, with the camera twirling between their legs and then watching as grinning women are flung towards the camera. More geometric patterns emerge, with the film culminating in one of the trippiest sequences as the camera moves through a four walled trench, each side lined with gorgeous, grinning women.

Unsurprisingly, “Dames” has a lot of grinning women. The number is probably the most conventionally Berkeley of all the ones in the movie, with his trademark geometrical patterns heavily in focus, as he uses semicircles to isolate and reconfigure his tap dancing charges. There’s also his usual amount of copious closeups of beautiful women posing. Their outfits (when they wear such things) emphasize the slimness of their bodies, the curves of their legs, and, naturally, the tap shoes on their feet.

And what would Freud say about those large bonnets the girls are wearing? Best not to worry about that, I think.

Reflections.

All three of the big production numbers in the film share several traits and meanings. All are built on reflections, on the way we view somethings through our own personal determination– whether it’s a pair of underwear as a perfect suitor, a cigarette advertisement looking like the girl you’re sitting next to, or every ‘dame’ looking similar and functioning as one giant whirligig of pleasure. They’re all fun and playful, as I’m sure you can imagine, but they fit in with the film’s points– your views on sex are a matter of perspective. The ‘trench run’ of women that finishes up “Dames” (see the picture up top of this review) as it twirls within their confines is perhaps the most surreal and perfect illustration of it.

But the movie is saving its last (and most direct) critique of the Hays’ Office for its notably short finale.

Rock it, Joanie!

“Try to See It My Way, Baby”

The last number of the picture is something special. It lasts less than a minute before a riot completely breaks out, never traipsing into one of Berkeley’s signature visual extravaganzas. But that doesn’t make it any less significant.

“Try to See It My Way, Baby” starts with Blondell, wearing essentially a number of ruffles and one big bow, snaking across the stage. Her anti-singing is still in full force, but it’s nowhere near as comically exaggerated as her earlier number. She waves one of her scarves at the box seat where Herbert, Kibbee, and Pitts sit watching, all properly tanked after a show filled with Golden Elixir breaks. Pitts hisses, “That creature is trying to lower you boys!” Herbert and Kibbee sure don’t seem to mind.

Besides Blondell waving playfully and belting out the tune, there are a series of scantily clad women dancing with one another across the stage. The curtain opens up, too, to reveal a grand suitcase filled with lovely ladies joining in the fray. The usual cinematic grandeur of Berkeley’s numbers is stripped away, emphasizing, in a rarity, the song itself. And from a bevvy of beautiful ladies playfully gallivanting on the stage to a censor sitting in the box, it’s not hard to figure out what this song’s title is referring to. For further reference:

Try to see it my way, baby.

Don’t break up a beautiful affair.

Try to see it my way, baby…

Continue with the dreams we share.

I try to see it your way,

Try to see your point of view.

But I don’t want to see it your way.

Because your way means we’re through!

But, as Ezra has planned, and in his stupor accidentally initiates, a brawl erupts to end the ‘beautiful affair’. The incoming Code was far more lenient on violence than it was on sex and sexuality, undoubtedly an inherited trait from its Catholic origins. Ezra in the movie makes the same assumptions about moral purity, assuming that sexual freedom is more dirty than violence against a fellow man and uses intimidation to bend the world to his will. Ezra even declares:

“Evil must be met with force.”

Luckily, the film understands an important counterweight to censorship– publicity. By creating something deemed scandalous, a show (or movie) would find their financial security guaranteed. This happened plenty of times in Hollywood, which is why salacious content was regularly added to movies; the more a fuss was raised about it, the higher the profit margins. But Hollywood was faced with a financial threat by the newly organized Catholic Legion of Decency’s ability to stage mass boycotts. That made the use of salacious material to sell a film a dangerous pursuit after 1934. (This would also eventually lead to any Catholic who watched the Jane Russell picture The French Line (1954) being automatically condemned to hell, but that’s a story for another day.)

But what of Hays’ fictional counterparts? Ezra, Kibbee, and the whole show ends up behind bars. When Pitts finds him sharing a drink with a big-eyed Blondell, she asks him what the rest of his moral majority friends would say. He scrunches up his face.

“Phooey!”

Guy Kibbee concurs with the ‘phooey’ sentiment.

Ezra has seen it Blondell’s way, all filled with sexiness and fun. But we know history, and the same argument held no sway for the Catholic Legion of Decency and the newly empowered office of the Motion Picture Production Code. Already by the time of this film’s release, studios were digging their heels in to little avail. Releases such as Belle of the Nineties and Forsaking All Others would be strong-armed and cut up, and the films of the thirties would descend into a miasma of safe, uncomplicated films.

Dames is usually regarded as a lesser entry in the Berkeley canon, but I respectfully disagree. It’s one last huzzah for pre-Code Hollywood, a big fat raspberry at censors while playing by their new rulebook. And the music ain’t bad, either.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- To promote the movie,Warners put out a short called “And She Learned About Dames.” In it, a homely young girl (Martha Merrill) wins a complexion contest and gets to tour the making of the movie, hosted by none other than heartthrob Lyle Talbot! (Or “had nothing better to do” Lyle Talbot, take your pick.) It gives an amazing glimpse at the backstage of Warner Brothers, while inter cutting plenty of footage for Dames for people to salivate over. Busby Berkeley makes an appearance, too, making a joke that would also get some use in Singin’ in the Rain. It’s definitely a throw back to simpler times when every girl in American was Dick Powell-crazy (or so Warners wanted you to believe), and it’s certainly worth checking out if you dig the film:

- For a longer rundown of the special features on the Dames DVD, which includes several Warner Brothers cartoons that exploited the film’s soundtrack, check out this piece at The Motion Pictures.

- The Acidemic Film Journal likes the movie, but doesn’t like Uncle Ezra:

Small wonder – DAMES came out in 1934, the year real-life versions of Uncle Ezra killed the spirit of louche cinematic insouciance in its cradle, i.e. ending the pre-code era. While Busby undoubtedly detests Ezra, it’s no fun watching him suffer; we came for breezy laffs and psychedelic dance numbers not Tea Party-style hysterics. It’s too close to home, man. Too relevant.

- DVD Beaver has some screenshots for this and the rest of the Busby Berkeley DVD collection.

If you like Ruby Keeler’s face, then you’ll enjoy this movie.

- Laura’s Misc Musings makes a note about a bit of nepotism:

Guy Kibbee’s brother, Milton, has a bit part as a reporter; Milton was a bit player who was not as well known as Guy, but he managed to accumulate 373 credits in two decades!

- FilmFanatic.Org doesn’t think this one essential, and notes:

[Writer Danny] Peary — clearly not an enormous Ruby Keeler fan — writes that she “does about 20 clunky tap steps to win a part in the show and does little else memorable except wear shorts” (!)

- 366 Weird Movies has a pretty fun breakdown of the film, and ends it with a note about Berkeley’s unfortunate future:

Aptly, Dames concludes with a drunken brawl, which was, alas, all-too familiar territory for Berkeley. The eternal mama’s boy had as a big a weakness for the juice as he did for the dames. A few months after the release of this film, a drunken Berkeley plowed into two vehicles, killing three people. Berkeley was charged with triple murder. Warner Brothers invested in Berkeley’s representation with legal top gun Jerry Geisler. Geisler’s work was cut out for him, but he eventually won an acquittal for Berkeley after two hung juries. The studio execs at Warner’s were impressed enough with the attorney that they would hire him again to (famously) get Errol Flynn acquitted of statutory rape charges.

- The trailer:

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is available on Amazon.

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 Comments

Grand Old Movies · December 15, 2014 at 1:21 am

I agree, I think this film is a major one in the Berkeley/Warners canon and has been unjustly overlooked. Its musical numbers are superb (the psychedelic “I Only Have Eyes For You” just for starters) and its humor against censorship is spot-on. As well as being an in-joke on the Production Code, there’s also a Warners in-joke line in the “Dames” number, when Powell welcomes “Miss Dubin, Miss Warren, Miss Kelly,” referring to the movie’s composer and lyricist (Dubin and Warren) and costume designer (Orry-Kelly). And I do love that Kibbee’s business is “sausage casings”!

Danny · December 28, 2014 at 1:45 pm

Ha! Hadn’t caught that in-joke, but that’s a good one. I am amazed that a movie that’s so thoroughly timely and referential still plays so freshly 80 years later. But that may be just me!

steve shuttleworth · December 15, 2014 at 2:13 am

“Dames” is also available in the Busby Berkeley Collection from Warner Home Video. It’s a great set that includes “42nd Street,” “Footlight Parade,” and the Gold Diggers of 1933 and 1935 films.

Danny · December 28, 2014 at 1:47 pm

I actually have that one, and it’s fun, especially for the bonus disk with all the Berkeley numbers put together. Still don’t like Gold Diggers of 35 very much, though.

realthog · December 15, 2014 at 2:58 am

An astonishing piece of work — many thanks!

Danny · December 28, 2014 at 1:47 pm

Well, thank you for coming by!

classicfilmtvcafe · December 15, 2014 at 12:25 pm

Awesome, truly in-depth piece on DAMES, Danny. I’m a moderate fan of the film. I always admire the intricate musical numbers imagined by the incomparable Busby. Plus, “I Only Have Eyes for You” is a truly beautiful song (especially the slowed-down versions of it). Being a fan of the post-Marlowe Dick Powell, I am always taken aback when watching him in his musical phase.

Danny · December 28, 2014 at 1:59 pm

Powell’s career is a pretty funny dichotomy. Murder My Sweet is one of my favorite movies, so it’s always a treat seeing him as a Jimmy or Bobby and just being as smooth as glass.

Jimmy · May 30, 2016 at 4:44 am

I disagree that “I Only Have Eyes” is an attempt at moralizing lust. Him seeing every woman as only one woman shows he has absolute devotion, in spite of occasional lapses in sexual attraction or love. To lust after a woman, or really women, is to disregard the individual and their particularities and abstract from them to see them as a representation of a fetish, or as a mere means to one’s own pleasurable state. But to concentrate on Keeler qua Keeler inevitably respects her idiosyncrasies and human characteristics instead of the body. If the number was to concentrate on her sexuality, the girls would be dressed more scantily as in the other number, “Dames”, and most certainly not concentrate on only her face. The obsession with her face lets us know that he has what CS Lewis called Eros, or erotic love; not erotic in the modern sense. It is what is meant by “being in love”, and is the state of appreciating the person as an end in their self, in surrounding times of happiness or trouble. Now this is an emotion like any other, and although it typically abstracts from and is usually the enemy of mere animal sexual attraction, it can equally be an enemy force to leading a virtuous life. But kept in its proper confines, it is nobler than lust; but whatever it is, it is most certainly not lust.

Alichael · March 19, 2018 at 7:47 pm

I completely agree with you Jimmy (Jimmy, as in Powell’s character Jimmy Higgins? Or just ironic that your real name’s the same?). Powell’s fixation on Ruby Keeler during the number was not sexual. Powell kept seeing Ruby’s face in the subway ads and in the 30 pictures of her face dancing around, and that’s it. And in the wonderful scene of the 30 dancing Ruby Keelers, they were all wearing beautiful floorlength dresses (and the singing was beautiful in that point of the song). They were not scantily clad. Also, I completely agree with Powell focusing on just Ruby was a sign of complete loyalty to just one woman. And Powell was not acting like a creeper, for the reasons I just mentioned, and because Ruby very clearly seemed to be very much in love with him too. And Ruby Keeler has always played in her films, and had been in real life, a clean cut girl who was not into promiscuity or cheating with other men. I love Ruby Keeler in I only have eyes for you, and I love her in all her films. She was a sweet, wonderful person in real life too from everything I’ve always read about her. After her marriage to Jolson (whoom she divorced because she was never comfortable with his wild lifestyle and his arrogance), she had a happy marriage with John Homer Lowe, was a great wife and a great mother to her kids. She was beautiful, inside and out. I love Ruby Keeler.

Jimmy · September 27, 2019 at 11:58 am

Hi Alichael. Checking on this years after. Yes, Ruby was particularly moral for someone in Hollywood, but she should not have deceived herself that divorce was possible. Love is only love when you continue in it when it is tested by someone less than holy, like Jolson was.

Bri · August 20, 2016 at 1:30 pm

Amazing butt shots in this 1934 gem

Risingson Carlos · July 21, 2017 at 6:45 am

I liked this more than it’s lack of plot made me think I would. And I enjoyed the goofy “drunk” slapstick routines.

But what I loved the most is finding out where Gondry found his inspiration for his video of The Chemical Brothers’ “Let Forever Be”

Comments are closed.