|

|

|

| Hildegarde Withers Edna May Oliver |

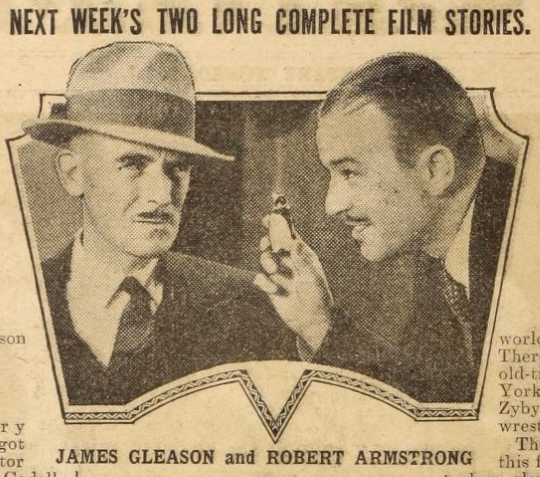

Inspector Piper James Gleason |

Gwen Mae Clarke |

|

|

|

| Philip Donald Cook |

Hemingway Clarence Wilson |

Barry Robert Armstrong |

| Released by RKO | Directed By George Archainbaud |

||

The Penguin Pool Murder: Whirlpool of Intrigue

We’re going to do something a little differently this week. Instead of my usual review, instead, here’s the first full chapter from my new eBook, Murder on Celluloid: A Companion to the Hildegarde Withers Film Series. Enjoy!

The Victim

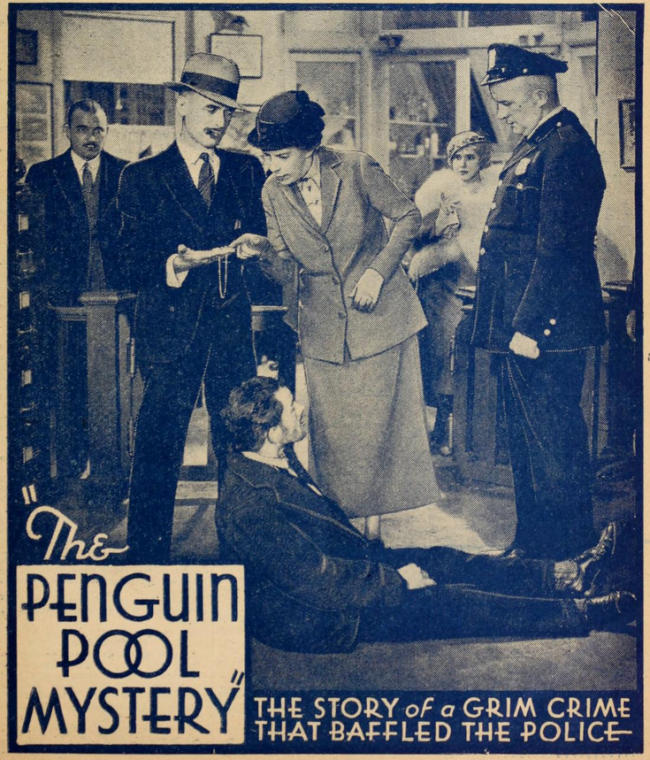

Gerald Parker (Guy Usher) – A stockbroker at the outset of The Great Depression (great shorthand for ‘shady jerk’), Gerald has recently doled out bad financial advice and is ignoring phone calls from anyone who’s upset by it. Furthermore he’s married to Gwen, a former dancer who has obviously lost that loving feeling. The revelation that she’s been sharing that feeling with someone else leads to him giving his wife a solid slap on the face. An anonymous call then tips him that she’s run off to talk to her former fling, Philip, and he chases them down to the New York Aquarium. A swift blow from Philip knocks him unconscious, and the last time he’s seen is when his dead body falls into the penguin exhibit. Unfortunately for the perpetrator, the body is discovered by amateur sleuth Hildegarde Withers.

The Suspects

Gwen Parker, the Unfaithful Wife (Mae Clarke) – A showgirl with too many problems, Gwen needs $5,000 to help pay back a bad investment. She seeks out Philip to help her out, but, after he knocks Gerald out cold, the opportunity to be rid of her cruel husband may be too tempting to pass up.

Philip Seymour, The Lover (Donald Cook) – An office worker who didn’t have enough money for Gwen just a few years earlier now appears to be in a much better position—and still in love with the inviting woman. He socks Gerald in the jaw and hides him in the aquarium. Did he finish the deed while he was at it?

Bertrand B. Hemingway, The Jilted Investor (Clarence Wilson) – The New York Aquarium’s director gets some bad news from Gerald in the morning about a failed investment. Bitter, Hemmingway finds Gwen and Philip and talks to them euphemistically about what he thinks should happen to men like Gerald shortly before the body is discovered. Is he bragging about the deed he just did?

Chicago Lew, The Thief (Joe Hermano) – Found with the dead man’s watch and hiding behind the fish tanks, Chicago Lew may have seen who committed the crime. He’s still wanted for his life’s ambition of being a pickpocket, though. Will he spill the beans—or, since he’s mute, at least sign them?

Barry Costello, The Lawyer (Robert Armstrong) – When the body is discovered, Barry is there to pick up the fainted Gwen off the ground. He seems quite taken with the girl, but his push to exonerate her sees him working awfully hard for others to take the fall. Could he know more than he’s letting on?

Hildegarde Withers, The Nosy Teacher (Edna May Oliver) – A schoolmarm who happens to herding a group of children on a field trip at the time of the murder, her hatpin momentarily disappears for a crucial period. Only later is it discovered that it may have been used in delivering the fatal blow upon Gerald. Is she guilty of killing him… or is she the only one with enough wits to solve the case of the penguin pool murder?

The Breakdown

“It takes a certain type to be a detective.”

“Well… I’ve noticed that.”

Hildegarde Martha Withers enters The Penguin Pool Murder at the eight minute mark when she trips a purse thief with her umbrella. She is quickly surrounded by a gaggle of children—black, white, Asian, Jewish, all in one set of disheveled school uniforms or another. She brushes off her umbrella from its mere collision with a criminal. “There, children, you see?” She emphasizes the ‘see’ with a sharp rise in her pitch. “Never try to evade the law with an umbrella between your legs.”

Hildegarde Withers is a tart, to be frank. She likes to bemuse herself and isn’t afraid to deflate anyone who acts below her expected IQ level for a second. She detests braggarts and corrals her classroom like a sergeant. She wears the immaculate uniform of an ideal 1930s schoolmarm: neatly pressed (if slightly stiff) suit jacket, skirt, gloves, a hat that seems a decade out of fashion, and an umbrella that can serve as a disciplinary tool when the occasion calls for it.

A distinct lack of a wedding ring completes the look. It’s not because of a lack of sex appeal—Edna May Oliver may not be Mae Clarke, but she still looks good in front of a camera—nor because Withers is lacking in any feminine charms. It’s hard to imagine that it’s not because there weren’t offers, but more that, to Miss Withers, the offers may not have measured up. It probably doesn’t help that Withers takes a lot of pride in her schoolchildren. She’s a professional woman whose stressful and demanding job she loves, making her a tough nut for any man to crack, especially in an era where it was considered an embarrassment to have a wife who worked. Still, she’s shown to have a soft spot for young love—a hint at a piece of a backstory never quite revealed, perhaps.

Edna May Oliver, who was also one of the initial inspirations for the character, finds the perfect balance for Withers and was a woman who eschews single adjective descriptions. Oliver, born Edna May Nutter, came from ‘fine New England stock’, and before you think that that means she’s a soup, it’s indicative of a rich ancestry.

A descendent of John Quincy Adams, she grew up in on the East coast. “Ever since I was a child I’ve wanted to act. But I wanted to be a great dramatic actress, and I’m sure I was at the age of five,” she explained with some humor. As a young child, she wrote, directed and starred in plays that she’d put on with her brother in their backyard. She initially wanted to be a singer, but a problem with her voice led her to try out the dramatic stage.

Oliver’s ability to play prim and proper made her a valuable commodity on Broadway, where she made her mark first in 1917. Her biggest break came as Parthy in Jerome Kerns’ Showboat, starring in both its original run and its revival in the early 30s. She also worked in silent films starting in 1923 and by 1930 was signed to the nascent RKO Pictures. Oliver’d already been through her only marriage by the time Penguin Pool Murder was filmed, a brief five year affair with a stock broker named David Pratt.

“No one takes me seriously,” bemoaned Oliver. A valued character actress, she was in high demand throughout her screen career in the 30s as a guaranteed laugh-getter. This is in spite of the fact that the actress detested doing comedy. “I don’t like being laughed at. I don’t think anyone does. […] We never let on that we don’t like to be laughed at,” she explained. “There is a side of us that we keep to ourselves, that we never give to the public.”

Not much of a partier among the Hollywood scene, Oliver preferred intimate gatherings and good friends followed by evenings at the theatre or live musical performances. She loved swimming and to travel across the globe, though planes frightened her and she never learned another language. She also had trouble hiding in a crowd.

“It’s this face of mine,” she explained. “No one can mistake it.”

But back to Ms. Withers, last seen tripping up a pickpocket named Chicago Lew. During a brief debate with a security guard and a policeman named Donovan (Edgar Kennedy), she asserts her right to any reward—and then is the first one to notice that Lew slipped away during the argument.

Isadore Merks is one of only two of Ms. Withers students who get a speaking role. Merks is nearly twice as tall as any of the other students, and obviously one of Ms. Withers’ favorite objects of ridicule. The actor, Sidney Miller, embodied a favorite joke for film writers of the era—the young Jewish boy. He plays much the same role in The Mayor of Hell (1933) and The Big Shakedown (1934)—with his part in Shakedown showing him haggling with Bette Davis over the price of an ice cream cone.

(Side note about Isadore: Ms. Withers’ crack about counting her class by the nose is a weird kind of non-joke joke, both incredibly un-PC nowadays and yet still so innocuous that it’s hard to take offense at. Some of the other Jewish jokes—such as Izzy doing a thorough examination of the stolen purse—are rather unfortunate.) (Further but unrelated side note: Miller grew up to become a composer and eventually a director, filming over a hundred episodes of “The Mickey Mouse Club” among other shows.)

The other singular student of hers is Abraham (for whom IMDB has no credit), a young black boy who discovers Ms. Withers hatpin on the staircase where, we later learn, it was unceremoniously left by the murderer. In a refreshingly non-stereotypical moment, Abraham is upset at the reward of no homework for discovering the pin— it won’t help him since he’s already two days ahead.

The recovery of Ms. Withers’ missing hatpin leads her to having to find the missing Isadore. He’s over at one of the aquarium’s displays, enchanted by the funny looking ducks—or, as we know them, penguins. That’s when the body drops into the tank and Penguin Pool Murder really gets going.

Our suspects make the scene one by one as the police arrive. “Some kid called up and said there was a dead man swimming with the ducks.” That’s Inspector Oscar Piper, played by James Gleason, getting off on a bad foot thanks to Isadore’s phone call.

Born on May 23, 1882, Gleason came into an actor’s family, with both of his parents running a theater company in the northwest. After serving in the Philippines during Spanish-American War, Gleason and his wife, Lucille, whom he married in 1905, both headed out on the road to make their fortune on the stage.

After a break from acting to return to service during the First World War, Gleason found success on Broadway as a writer and character actor. Plays that came from him included Is Zat So? (1925) which ran for 618 performances and Rain or Shine (1930) which made it to 356 and was later adapted into a film by Frank Capra. His work on both sides of the camera was noticed out west, and he began acting in films regularly after 1927’s Count of Ten. He went on to co-write Best Picture winner The Broadway Melody the next year.

Gleason would end up garnering over 150 acting credits, including parts in A Free Soul (1931), Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), and The Bishop’s Wife (1947). This run also included an Academy Award nomination for his part in Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941) as an irascible boxing manager.

Gleason would end up being the glue that holds together RKO’s Withers series, appearing in all six of the films as the prickly love interest Oscar Piper who either would call on Hildegarde or merely find her nearby whenever a murder was afoot. His grumpiness overlaid a lot of heart, and the feelings that Oscar had for Hildegarde, whether romantic or friendly, are one of the key ingredients to the series’ success.

Back to the picture. With Piper there, he goes to the penguin pool to investigate. The security guard is trying to revive Gerald with a rather suggestive looking version of CPR as Piper and Withers enter. After a quick examination, Piper declares the death a homicide. The chemistry between Piper and Withers is established quickly.

Withers: “I realized that [it was a homicide] a half an hour ago. That’s why I had one of my pupils call the police!”

“I’m surprised you thought the police necessary,” he cracks back.

She lets out a quick cough, deflated.

Piper gathers the suspects in Hemingway’s office where Withers takes helpfully takes down the minutes of the interviews—an act that makers her essential and helps to quickly root out inconsistencies. Piper even admits it ain’t a bad idea.

Since we have most of the malfeasances gathered, it probably isn’t a bad idea to run through the supporting cast now. Penguin Pool Murder also benefits from a fairly robust cast of character actors, some who were, at the time, strong B-listers.

The most impressive resume comes from Mae Clarke, pretty much the premiere hard luck girl of the early 1930s ‘pre-Code’ era. Her most iconic moment remains getting a grapefruit in the kisser from James Cagney in The Public Enemy (1931), but her filmography from that time was littered with characters who either committed suicide or were unceremoniously murdered for dramatic effect; see Waterloo Bridge (1931), Three Wise Girls (1932), and, of course, Frankenstein (1931). Her role here fits in that mold quite succinctly, though it almost wouldn’t have worked unless the movie wasn’t bookended by Gwen being slapped.

Donald Cook also had a role in The Public Enemy, but that’s because his dark complexion made him an ideal actor to wield a machine gun and drive through the city streets. He would later be the first actor to portray Ellery Queen on the big screen in the quite fun The Spanish Cape Mystery (1935), though that was his only outing as the famous detective.

Robert Armstrong is best remembered for a part from the year after Penguin Pool’s release, that of the ambitious director Carl Denham in King Kong (1933). Armstrong’s square jawed looks made him a fairly big star for RKO, and his ability to be cruel, cunning, and sometimes fairly funny gave him great versatility.

Interesting side note: Armstrong had long been good friends with James Gleason, having worked under him in a touring theater group and getting his big break on Broadway under Gleason’s tutelage.

Clarence Wilson, the fussy aquarium head, had been working in pictures since 1920 and seems to have cornered the market on crotchety and eccentric bureaucrats. He racked up nearly 200 credits in 21 years, often in small roles but with a certain sense of irresistible irascibility. Wilson would also pop up in another detective movie a few years later, though it would be as a victim in 1936’s Perry Mason whodunit The Case of the Black Cat.

But back to the interviews, where Piper and Withers are once more trading barbs. She’s already adopted a moniker for him– “Young Man”—something playfully subversive of his position, as well as subtly flirtatious. Piper, for what it’s worth, takes her insults in stride. She may not respect his authority, but he doesn’t respect her authority either. This, naturally, will change as the film goes on.

The film cuts away briefly to show the security guard catching Chicago Lew back among the tanks. Lew uses sign language to indicate something that offends the policeman. Side note: Chicago Lew is Joe Hermano’s only credited screen role. Hermano was deaf and dumb in real life as well, and for a long time sold newspapers outside Hollywood nightspots. Known affectionately throughout Hollywood as ‘The Dummy’, when his newspaper job dried up, many directors and producers helped him out by giving him work on pictures in background scenes. Star Richard Dix, in particular, made sure that Joe got extra work in many of his movies.

And so we have our cast of suspects. One of the best moments of the movie comes when Barry, questioned on his appearance at the aquarium and sudden interest in Gwen gives a quick speech on penguins. “Have you ever noticed them? […] They’re like funny little old men in dinner jackets. Slightly drunk. They’re human without being offensive!”

Withers, once he’s out of the room: “I’d never trust a man who was a penguin fancier!” Yeah, that’s probably a good call.

Piper is pretty frustrated by the initial investigation as he finds that a series of contradictory stories and confessions leave him at square one. He points at the penguin pool’s sole occupant:

“If that penguin could talk, I bet he could tell us who did it.”

“And if that penguin could laugh, I know who he’d be laughing at,” snickers Withers.

“You know, I can’t quite make you out, Miss Withers.”

She smiles. “Then this is a busy day for you, Inspector. Now you have two mysteries to solve.”

The most unassailable delight of The Penguin Pool Murder is the relationship between Hildegarde and Piper. Fans of classic Hollywood—or hell, most any era of Hollywood—can be hard pressed to find romances between two people of a certain age or a certain physical type portrayed on screen with any manner of verve or wit. Here, though, Withers and Piper crackle in their interactions.

In fact, much of the movie is watching how the two’s admiration and affection grows in between barbs. The morning after the murder roundup, Piper comes to Withers apartment to pick up her notes that she’s helpfully typed up, only to find himself served a massive breakfast with waffles, bacon and eggs.

But there’s tension still. As the two playfully flirt, Piper can’t help but feel his sense of nobility come out. He can’t let Hildegarde continue with the investigation even though she’s been a big help.

“A woman detective always looks like a woman detective,” Piper explains.

She sniffs. “But what about a woman detective who looks like a school teacher?”

With it appearing that her part in the investigation is over, Piper thanks her and leaves. Hildegarde can’t restrain her disappointment. In a brief second of introspection, we see Oliver recall all of Hildegarde’s pain from years of frustration.

“School teacher,” she mutters. “Tch.”

A chance phone call reveals that Hildegarde isn’t out of the running as a suspect yet. Piper takes her back under his wing and the chase continues.

Withers decides to take the chance and heads out on her own investigation, and investigates how Gerald was led to the murder scene. She stops to make fun of his secretary’s makeup and gets the lowdown on who called in the threat.

“Are you sure it was a man’s voice?” demands Withers.

“Well it ain’t likely that a woman be calling me baby, is it?”

“No, not so far downtown as this. Now, baby—I mean, uh…”

This is probably one of the more preeminent moments that indicate the movie is a ‘pre-Code’ production. Pre-Code generally refers to movies filmed between 1930 and 1934 before mandatory film censorship kicked in due to pressure from religious groups. Pre-Code films, which include movies like The Thin Man, Duck Soup, and Trouble in Paradise, are often more risqué and pushed the boundaries of what a more conservative country could tolerate.

The joke here is a reference to the gay scene in New York. After mid-1934 and until the Code’s dissolution in the late 1960s, even hints at homosexual behavior would be strictly kept out of mainstream cinema.

The movie itself is a great window into early 1930s filmmaking. 42-year-old George Archainbaud immigrated to the United States in 1915 where he started working as a director. His career is full of prolific B-picture action movies, with his output around the time of Penguin Pool including Thirteen Women (1932), which is sometimes considered the first ‘slasher’ movie, State’s Attorney (1932) with John Barrymore, and The Lost Squadron (1932), a critically acclaimed story of a former-World War I fighter squadron desperate for work and ending up at a Hollywood studio. Westerns became his stock in trade, though, as a friendship with Gene Autry would see them collaborate on films and television shows in the 40s and 50s.

Archainbaud isn’t the most stylish of directors, but he does do a few things expertly that add to the movie’s atmosphere, using varying angles, shadows, and, yes, special effects to give the movie a gloss that a lot of detective pictures of the era simply couldn’t be bothered with.

Take, for example, an early tracking shot as Mae Clarke enters the aquarium, breezing past Hemingway who recognizes her. It’s a pretty simple shot as the camera stays with her until it catches Hemingway and then stops on him reflecting on her, but it gives depth to the room while demonstrating how single-minded Gwen is at that particular moment.

Later there’s an excellent shot where Philip lays out Gerald with a single punch. It’s from high above, making the violence contained, but also giving the small area a claustrophobic vibe. Shots like this are unusual in programmers, but Archainbaud uses the moment to underscore the trouble Gwen and Philip are suddenly in.

There’s also an interesting visual motif with the subjects of the aquarium. The movie’s first few shots are of fish, naturally, but they’re not being casually observed. In fact, they’re actually staring back into the camera. Archainbaud adds this to mirror both the characters in the movie and the audience themselves, unable to do anything to stop the ensuing bloodshed.

Spoilers follow about the end of the film.

As for the mystery’s solution, Penguin Pool does a great job with misdirection. While seasoned mystery fans may figure out the killer early on, the film’s hints at the backstory are pretty scattered. Besides the first early phone call, the references to Gwen’s need for money are quickly pushed to the background. Gwen also obviously recognizes Barry as soon as she wakes up from her fainting spell, but the movie plays it off as panic rather than realization.

But Barry being the villain is unsurprising. Besides his stated disdain for the human race, he’s extremely shady. As Piper’s respect for Hildegarde grows, Barry’s ire with her nosiness obviously matches that. In the last scenes in the film, where we see Barry attempt to discredit Hildegarde with a ridiculous series of accusations (which Hildegarde, amazingly, had predicted he would do earlier), we see the callous desperation in him. When he’s finally revealed and goes for his gun, his full serpentine nature is exposed.

Unsurprising for a work from the early 30s, the triumph is pure governmental competence outwitting selfish thieves and braggarts. Both Hildegarde’s job as a teacher and Oscar’s job as a police officer are those of public servants, and their unity allows one another to find newfound respect for each other’s roles in society. Both of their careers have taught them fearlessness.

Meanwhile, the cast of assorted suspects are far less auspicious. Hemingway, whose petulant nature and pointed face make him seem so suspicious, quickly turns out to just be a huge dork. He doesn’t make threats; he makes analogies involving fish mating rituals. Gwen and Philip are somehow even more neutered than a neurotic aquarium head—an office drone making some good money and a showgirl who married the wrong guy, fell in love with the wrong guy, and went to the wrong guy for help (a triple threat!).

But it’s who the film’s villains are who speak volumes. Gerald, though he’s obviously a victim, is still a nasty piece of work, abusing Gwen and shrugging off how he’s ruined Hemingway’s financial future. Penguin Pool isn’t really concerned with making him sympathetic; it’s how he’s murdered that will garner the most pity, as it’s so quiet and nasty.

The film’s other villain is a lawyer. No need for much of an analysis there.

But let’s go back to the important part of Penguin Pool which isn’t so much the murder mystery, but the sexual chemistry between Withers and Piper. What’s fun is watching how the film lets the duo’s banter grow naturally, and their respect grows for each other as the film continues. Piper’s constant cigar chomping and Hildegarde’s flustered fluttering indicate that there’s more than meets the eye in their physicality.

The movie ends with a nice kicker. Hildegarde still hopes for a romantic reunion between Gwen and Phillip, despite the fact that she almost put him in the electric chair to save her own neck. Gwen emerges from prison to find Phillip there. She ignores him; he slaps her. Young love ain’t all it’s cracked up to be.

But that doesn’t mean love is out of the air. Piper turns to Hildegarde and she sniffs. He thanks her for all the work she did on this case and says he couldn’t have done it without her.

“Are you proposing we start a detective bureau?”

Piper shakes his head. “No, I’m just proposing.”

The abruptness of the ending, with Piper pulling Hildegarde out the door with only a few minutes to meet the Justice of the Peace, is the perfect punchline for the film. Penguin Pool, which functions as a pulp mystery and a catalogue of Depression Era foibles, is a romantic at heart.

Unfortunately, as is bound to happen with sequels, the pieces that are easier to write get carried over, and depth is sacrificed for humor. But these pieces don’t matter, since the core relationship at the center of the mysteries is so energetic and zippy that it’s impossible to resist.

End spoilers.

The Penguin Pool Murder is an exceptional chapter in the history American murder mysteries, a Depression Era ode to unconventional love stories and old fashioned know how. While the mystery may not leave too many people puzzled (as Hildegarde notes, “Funny how simple the answers seem once you know them.”), the romance and comedy is what makes it—and the series— so memorable.

Trivia & Tidbits

- Filmed between September and October of 1932 and released in December. It would be one of RKO’s biggest hits of the year.

- The New York Aquarium featured in the film was located in Battery Park on the southern tip of Manhattan until 1941. It reopened on Coney Island in 1957.

- The titular penguin was played by the appropriately named Oscar the Penguin. The blog Ludic Despair quotes the book Wild Animal Actors by Frances Mary and Helen Mae Christeson in discussing his tumultuous adventure in making this movie. Apparently shortly before filming, Oscar escaped and made his way over 100 miles down the Californian coast before being recovered. Oliver was apparently hurt by the snub and fed the animal coins and rocks between takes. (Please take this with a grain of salt since I could not confirm it in a copy of the book itself since the closest copy to me is 3,500 miles away.) Oscar would also appear in “Blue Blackbirds” (1933), No More Women (1934) and Barnacle Bill (1941). He was paid $125 a week, which wasn’t bad money for a penguin.

- There’s a throwaway line in the film where Piper notes that, “we sent a woman to the electric chair a short while ago”. This is a reference to the 1928 execution of Ruth Snyder for the murder of her husband. It gained national notoriety when a reporter for The New York Daily News took a picture of the execution in progress with a hidden camera.

- There’s a quick reference to Lydia Pinkham in the film. Pinkham was a late 19th century marketer for a ‘woman’s tonic’ for ‘female complaints’, AKA menstrual and menopausal pain.

- The Greek witch Circe gets a namedrop as well. She was the witch who’d transformed Odysseus’ crew in The Odyssey.

- Sir Walter Scott is a Scottish writer most famous for Ivanhoe, if you’re wondering why the name sounded familiar.

- Mae Clarke had suffered a nervous breakdown in June of that year before filming commenced, and was supposedly working on a book about the experience called I Disappeared for Months. It doesn’t seem anything came of it. Mae’s opinion of RKO, as stated in her autobiography Featured Player, was that it was ‘cold’. She also noted about her part in Penguin Pool (with spoilers):

[N]ot all my whores were good ones. In Penguin Pool Murder, she was just a bad girl. Cook at the end slapped my face good and I deserved it. And I hated it because I deserved it. I didn’t like those kind of roles, but they were meaty.

[…] It wasn’t so much filming it, because you didn’t know what you were doing or why you were doing it. But the people themselves were fun to be with. Edna May Oliver was a joy.

- The movie was previewed in November of 1932 according to Hollywood Filmograph to positive results, with the gossip columnist noting that Gleason and Oliver were a “wow”.

- The same issue of the Filmograph that noted in that last bit also has a piece talking about Stuart Palmer being given a new contract at RKO (he’d arrived in July to adapt his book to the screen). The piece explains that he was 27 and had written over 7,000,000 words across stories, plays, and film scenarios.

- The Film Daily lambasts the film, saying the ‘forced comedy’ hurts the ‘fair mystery story’ and blames too much mugging.

- Exhibitors reporting in the Motion Picture Herald ranged wildly and without much consistency—a lot of people showing it liked it, and though it didn’t draw huge audiences, it seemed to get good feedback. One person complained that the word ‘murder’ in the title kept the kiddie audiences away and hurt business.

- The Motion Picture Herald called it refreshing and told exhibitors that a good publicity event may be to get a real penguin down to the theater for patrons to gawk at (if at all possible). So, yes, this film led to a great number of terrified penguins all over the country.

- Helen Boyce, reviewing for The International Photographer, notes that, “It ends just the way we like to have ‘em end.”

- Photoplay called Edna May Oliver, “a scream” and told its audience not to miss it.

- In January of 1933, Penguin Pool Murder was put on a double bill with Little Orphan Annie, which didn’t work too well apparently Annie However, Irene Thirer of the New York Daily News gave the combined double feature 4 ½ stars, raising the ire of the Hollywood Reporter since that scale was out of 4 stars.

- An article in the January 1937 issue of Silver Screen called “Whodunit” discusses the state of detective pictures, describing all of the major series at the time, including Philo Vance, Bulldog Drummond, Nero Wolfe and, naturally, Nick and Nora Charles. The writer, Janet Graves, uses the opportunity to bemoan the lack of women detectives on the screen rather brilliantly:

What, no women? Well, very few. The thrillers are neglectful of our sex, when they are not downright insulting. All the heroine has to do is scream at regular intervals and get herself into incriminating positions or dangerous spots from which the hard-working hero must rescue her. Or she may even make an infernal nuisance of herself, like the charming but exasperating young lady that Rosalind Russell played in Rendezvous.

Edna Mae Oliver alone has upheld the honor of her sex, as the screen’s sole lady detective, the snooping school-teacher who made her first appearance in Penguin Pool Murder, with the tough, querulous Jimmy Gleason playing stooge.

But why stop there? Claudette Colbert would certainly make a clever, as well as decorative sleuth. Joan Blondell’s long acquaintance with the ways of movie crooks qualifies her also. Maybe a feminine Sherlock wouldn’t be realistic. So what? One of the most engaging features of the thriller is its bland disregard for realism.

- One delightful letter to Photoplay in June of 1933 talks about the author’s fondness for Oliver and how the picture helps her keep her mind off of her tough times. It’s kind of silly, but touching nonetheless. It reminds me of all the reasons I like researching this stuff.

Important Link

Now available as an eBook at Amazon is my newest book, Murder on Celluloid: A Companion to the Hildegarde Withers Film Series.

Now available as an eBook at Amazon is my newest book, Murder on Celluloid: A Companion to the Hildegarde Withers Film Series.

The book includes the above article and reviews of the other six films in the Withers film series, Murder on the Blackboard (1934), Murder on a Honeymoon (1935) (all starring Edna May Oliver). Murder on a Bridle Path (1936) (starring Helen Broderick), The Plot Thickens (1936), Forty Naughty Girls (1937) (both starring Zasu Pitts), and A Very Missing Person (1972) (starring Eve Arden). There’s also a look at the book series’ author, Stuart Palmer, a bonus review of the tangentially related Mrs. O’Malley and Mr. Malone (1951), and my own reflections on the series.

If you want to pick this up, it’s only $0.99 and you’d be doing me a solid.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is available as part of the Hildegarde Withers Mystery Collection on Amazon and Warner Archive. As someone who’s written a book on the movies contained in the set I highly recommend getting it! … And, of course, the book…

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Comments

Vienna · May 13, 2015 at 4:06 pm

Love this film. Thanks for such a detailed review.

Ben Frey · May 13, 2015 at 9:27 pm

I think I’ve seen all six Hildegarde Withers films (I may have given up on the last one). The chemistry between Oliver and Gleason was always a delight and seemed genuine. I wish they had married.

Danny · May 25, 2015 at 2:50 pm

Ha! Well, I think Gleason was pretty happily married otherwise, and Oliver was pretty happy as an independent woman doing her own thing. But they do have great chemistry for sure.

lmwilker · July 22, 2019 at 9:58 am

I love this film. It is definitely one of my favorites. At the end of the Penguin Pool Murders it seems like Gleason proposes and Oliver accepts but they don’t seem to have gone through with it in the next two films. I do remember a scene from one of the 2 sequels where Oliver is wearing what looks to be a rayon dress and as she bends over Gleason checks out her backside. It was funny but also really hot.

Comments are closed.