|

|

|

| Megan Davis … Barbara Stanwyck |

General Yen … Nils Asther |

Mah-Li … Toshia Mori |

|

|

|

| Jones … Walter Connolly |

Bob Strife … Gavin Gordon |

Captain Li … Richard Loo |

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- You may not be old enough to remember this, but at one time miscegenation was illegal in many states in America. If you were white and you met a nice black person, or Asian person, or even native American, you were not legally allowed to be married. You could even be charged with a felony for doing so. These laws were on the books until 1967 when the Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional. There’s a lot more about those laws here on Wikipedia, but the point of this bullet (you knew I’d get there) is that this film, the one we’re talking about, involves miscegenation. And not even the usual “white guy grabs a sexy squaw” sort of narrative that lingers in the background of pics like Cimarron, but “a Chinese dude goes after a white woman’s virtue”. Hubba hubba.

The Bitter Tea of General Yen: Eroticism in the Orient

“We’re all of one flesh and blood.”

It’s been 80 years since the movies I write about here were made. I know this fact—my wife reminds me about it fairly often— and I’m sure you’ve picked up on it as well, but I think that’s an important thing to keep in mind especially for today’s film, one of the oddest anomalies in the history of one of America’s greatest directors and greatest stars.

The Bitter Tea of General Yen is not what we’d consider politically correct today, even if at the time it was scandalous. It features an actor in yellow face, pure strain white missionaries who defy violence to rescue orphans, and a Chinese man who kidnaps a white woman in an attempt to chip down her virtue. At the time it was daring, nowadays it would be labeled as ‘politically incorrect’– even if much of what it does still counters a number of strongly held cultural myths that endure.

It’s both ahead of its time and a relic, a curiosity for the ages. That The Bitter Tea of General Yen is a ribald example of grandiose and textured filmmaking doesn’t hurt either.

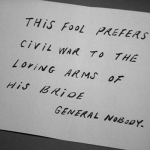

What is love? Baby don’t kill me. In this civil war.

The plot: during an event that the film’s title card helpfully calls ‘The Burning of Chaipei’, we are taken through the chaotic streets of Shanghai to the joyous mansion that houses a number of American missionaries. One of their group, Bob, has invited his childhood sweetheart, Megan, to China to get married. We learn that Bob and Megan are strict Protestants and haven’t seen each other in three years; frankly, if the two of them were any more chaste, they’d have to be sharing matching Barbie genitalia.

Megan’s route to the house, compounded by the raging civil war, has her driver killed carelessly by a passing car. She gets out to lodge a protest and is shocked when no one seems to notice or care. The man who was in the back of the car steps out, and we see for the first time the suave General Yen.

He is demure to the outraged Megan, only infuriating her more: life comes cheap in China, he assures her. Believe it or not, this fails to win Megan over, and, after she senses that he may be flirting with her, she storms off to the wedding.

“Hi, you’re the center of attention!”

During this introduction at the missionary’s homes, Capra jumps between people in the sea of white worrywarts. The white Christians gathered give little thought to the war outside their front door, more preoccupied with the fantasy of the romance between Bob and Megan. Expressionless Chinese people sing, perform, and wait on them, all emotionless slaves to the missionary’s gossipy celebration.

We eavesdrop on a priest tell one short, damning story about Mongolians he preached to, revealing much about both the missionaries and their audience. The story he tells is how he explained to them the crucifixion of Christ, and how the Mongolian’s rapt attention later turned out to be because they were fascinated by the execution methods rather than the preacher’s moral.

That the Mongolians would side with the Romans in such a situation seems rather like a given, but the missionary blasts them as barbarians. These words, along with a few other unkind racial slurs, drip from the party goer’s mouths. But more on Christ in China in a little bit.

“Oh, Bland! Er, I mean Bob!”

When Megan arrives, she finds that Bob must skip the wedding, as a school full of orphans needs him. She voluntarily tags along, and in the chaos of the escape Megan is knocked unconscious. She awakens on General Yen’s train. He’d saved her from the crowd, and is now taking her out to his stronghold in the countryside. (And, yes, that means Megan is literally shanghaied from Shanghai.) She tries to fall back asleep, but pulls the sheet to cover herself once she notices how his gaze lingers upon her.

Yen is polite, but strikes Megan as needlessly brutal. She wakes up in the morning to the sound of firing squads in the courtyard. Yen politely offers to move them out of earshot, but she is outraged; murdering those who turned against him is wrong. He insists that imprisoning them would have brought about the same result since they would have merely died of starvation. Which option is less cruel?

Out of sight, out of mind is the American expression. Yen finds out that Megan is presumed dead in Shanghai, and decides to see if his charms can wear her down by cutting off her contact with the outside world. As Yen and his American adviser, Jones, have to contend with keeping their followers in line, Yen finds his thoughts more and more concentrated on teaching Megan the darker truths about the world. Traitors lurk, up to and including Yen’s mistress, the lovely Mah-Li (Toshia Mori).

She doesn’t look too thrilled about this.

Things become a chess match between Yen and Megan, while Yen’s province spins out of his control. When he finds that Mah-Li has been feeding information to his enemies, Megan steps in to vouch for the young and beautiful girl. She assures Yen that he will know true happiness once he gives Mah-Li true forgiveness, and he acquiesces; Yen sees this as an opportunity to teach Megan a lesson in human nature. “What are you doing?” Jones asks, bewildered. Yen smiles. “I am converting a missionary.”

As Yen had expected, things backfire, and even more gravely than he could have imagined. Megan’s naivete allows Mah-Li to reveal the location of his train car filled with wealth, and after a bloody raid, he is ruined, left with nothing but a target on his back. His revolution is in shambles, and he finds himself virtually alone in his cavernous palace. Megan and Yen, often adversaries and of vastly different background and beliefs, come together at last.

The Yellow Swine

“[Christ was] a fool enough to hope.”

Reading other reviews of the film– as I am apt to do– I was amazed at the variety of reactions, one even going so far as to label General Yen, a “personification of evil”! I think you’d have to be hard pressed to get that from the character, especially as Nils Asther plays him as suave, funny and charming. In fact, I think the very worst you can say about the General is that he’s a selfish pragmatist.

The General makes no patriotic speeches about China, but I surmise that he doesn’t feel that he has to. His rebellion isn’t purely about nationalistic fervor nor racial purity. He is rebelling, as far as I can fathom, because he is no one’s master but his own.

Even Mah-Li, who’s deceptions topple Yen, is shown as being a young woman with a love of family and poor choices in men.

Where a lot of reviewers and the movie part ways is their inability to reconcile Yen’s actions with the barbarism he demonstrates, which seems to ignore most of the words he says and points he makes– unsurprisingly demonstrative of quite a number of the film’s themes. For in 1933 the greatest sin of all isn’t simply the taboo of interracial romance (though more on that in a second), but a skewering of the belief that America owns the moral higher ground in every situation that involves a ‘lesser’ race.

That brings me to one of the things that fascinated me about the film was its refusal to back away from tough discussions. Compare this to Capra’s The Miracle Woman from the year before. I think we can say now that Miracle Woman is a great film that doesn’t skewer the topic of evangelism as neatly as it could have; Capra himself admited he chickened out. But the wonderful thing about Yen is that it takes on the less-controversial topic of missionaries and spits in its face. It’s hard to picture American missionaries as anything more than ankle biting, condescending racists after watching their portrayal here.

And, ironically, Yen seems to be the only person who sees Christ’s teachings of hope for what they really are rather than as a way to mark one’s own perceived superiority. But, no, the missionaries are obsessed with their own fetishism for Christ on the cross, more interested in his death than his teachings. But that fetishism also works a good bridging point for the next step in the film: the sexual enticement of Megan by General Yen.

The Yellow Menace attending its nightly duties.

Sex and Supplication

“The conquest of a province or the conquest of a woman… what’s the difference?”

The idea of domination in sexual foreplay is pretty widespread, but commercial fantasies paint it as powerful men yearning to wither under the whip of high heeled dominatrixes. Suggestions of women enjoying sexual domination became fairly taboo when most pointed out that saying that a woman could desire to be dominated by a man is a rather shitty narrative considering that women have been unwillingly dominated by men for most of humanity’s existence.

Now, little nuggets of resistance pop up every so often (hi, Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey), but the general mood of the public has soured on these Harlequin-esque stories of illicit romance cut with sexual obedience. Many people resist reading this sort of thing into Yen, instead noting the way that Megan and Yen’s foreplay can be read is via the term ‘Stockholm Syndrome‘, wherein a person is coerced into feeling affection for their captors against what should be their better reason.

But Yen’s domination is less remarkable and coercive when you realize what Bob had planned for Megan. While I’m not condemning the fact that he rescued a school of orphans (always a fun sentence to write), he’s kept his own childhood love at arm’s distance for three years, and clearly plans to put his missionary work ahead of her in their future. He is sublimating her into a different kind of bondage, the second fiddle to a noble cause, and she’s more than happy to play that role. It’s not hard to believe that Yen, who finds missionaries and their influence on China degrading, would seek to deprogram Megan from this misguided attempt at eager sacrifice, no matter the cost to them both.

Learning a cruel lesson.

But look at Megan’s own yearnings, seen far before she’s been taught her ‘lesson’ by the general. After only a few days in his care, she falls asleep under the dreamy moon while soldiers and their girls frolic in the fields across from her balcony. She nods off into a hazy dream.

Here we see her in her palace bedroom, recoiling on the bed as a force breaks through the door. It’s Yen, but with the long spindly fingernails and pointy ears, a caricature of the Chinese race, arriving to do plenty of unspeakable things to the screaming Megan.

But a protector arrives, dressed in a suit and a mask. With one powerful punch, he knocks the invader into the wall, where he vanishes. The protector takes off his mask as Megan comes in for a kiss to reveal General Yen again, this time more trim and neat in his Americanized suit. She pulls him onto the bed and, in rapturous appreciation, keeps pulling.

Hubba hubba.

Megan, for all of her weaknesses, and her ability to recite Christian platitudes with conviction if not yearning, is an equal to Yen throughout the film. The thinly veiled eroticism of the final supplication, dressing in Chinese clothing and kneeling at the feet of the defeated Yen, is not so much an act of degradation but admission of knowledge and his rights as a man sans the prefix ‘Chinese’. This is what makes the film’s ending something dangerous to behold.

The Look of Lust

The film’s look is beautifully dreamy, revealing a sensuous art design and directing style that many have put on equal with Josef von Sternberg. From the filmed chaos at the beginning to the hazy moon drenched nights to the assault on Yen’s railcar, the film switches moods with an incredible ease. It’s a movie that’s wonderful to simply sink into.

Director Frank Capra was on a roll after The Miracle Woman and Ladies of Leisure in creating movies that utilize dark blacks and precise lighting to emphasize character’s glows and other interesting visual geometry. I’ve noticed in a few screenshots this interesting tidbit:

Namely, that a shadow entombed Buddha seems to follow Megan around through most of her escapades.

But also take a look at that set design, ornate and domineering. The beauty of this film cannot be understated. I’ve got plenty of more in the gallery, and they’re definitely worth ogling at.

Better yet, it’s served well by a talented crew of actors. Barbara Stanwyck, mostly known for her own dominating personality, is evenly matched with Yen. Watching her as Megan swallowing her pride at the end means so much more than if a lesser actress attempted it. She is smart and proud, and even if the movie breaks her, it gives her the poetry of one of the better film endings of the era. She never becomes a conquered woman, but a full one, one who has seen past all of the racism that her culture and religion has pressed into her and come to understand humanity on a deeper, more elegant level.

Nils Asther plays General Yen in what must be said is pretty good yellow face. His Yen is controlled, but delights in delicate humor and a cool intelligence; he’s about as good of a representative of the Chinese race as you could hope for from a white man in makeup.

Toshia Mori and Walter Connolly both make good impressions from their roles as well. Mori would have been a star if it weren’t for Hollywood’s own racist practices at the time, and Connolly plays exactly the kind of cantankerous bastard friend we all wish we had. Which brings me to the most pointed knife in Bitter Tea‘s repertory.

Seriously, one of the greatest film endings of the time.

The American Gospel

“As they say in your country, money talks.”

Capra brilliantly contrasts the role of the Christian missionaries in the film with the other kind of American missionaries, the war profiteer. Yen’s adviser, Jones, is an immoral scoundrel, who’s a good friend as long as there’s an opportunity to make money. Yen defines this as such, noting that as long as his goals are the same as Jones’, Jones is loyal to him, making him much easier to please than the locals who want to be treated humanely and/or not shot.

Jones is shrewd, but in this fight as far as it affects his margins. When he’s introduced to Megan, she initially thinks of him as a kindred American; when she discovers his true role in eking out taxes and exposing the traitors for execution, she’s appalled. He’s not a monster to Americans, since we recognize him so well as one of our own, someone with charm, bluster and a desire for power, but it’s hard to ignore how most of his actions are undeniably cruel and selfish.

And, to the point, Megan realizes she’s not much different. Both have come into the country with their presumptions about what they’re going to find, and have been ingrained with the belief that their moral or financial superiority will gain them the satisfaction they deserve.

After Yen’s final cup of bitter tea, Megan and Jones sail on a ship back to Shanghai. In a series of long, beautiful shots and one long, drunken speech from Jones, we see that he’s learned something from their experience about nobility, life, and poetry. Believe it or not, both have discovered that the Chinese aren’t bloodthirsty simpletons, and that love and friendship may beat out money and blind spiritualism in being the most potent weapons in changing the world.

And that is a damn good message.

Gallery

Here are some extra screenshots I took. Click on any picture to enlarge!

Trivia & Links

- The TCM DVD includes an introduction by directors Ron Howard and Martin Scorsese. They discuss Capra’s gift for movement and light and shadow. Howard notes that the film also starkly shows, “the dark side of American imperialism as an aggressive means to not spread liberty, but to make money.” It’s short but sweet.

- There’s also a short film Columbia made included on the disk called “Screen Snapshots” that talks about the creation of a motion picture– using Bitter Tea as its the example. This is about as close to an actual behind the scenes featurette as you can get in the day, and it features a lot of cool scenes showing set construction and makeup tests. Definitely check this out.

Case in point: here’s a cool makeup comparison. Asther on the left, Yen on the right.

- Speaking of our leading man, Nils Asther: Reluctant Star by Tim Lussier looks at Asther’s career and shaky relationship with Hollywood. His most famous roles, outside of this one, are both opposite Greta Garbo: Wild Orchids (1929) and Standard Time (1929). In Orchids he even played a Javanese suitor, though still a man more carefree than General Yen. Asther was much happier to segue into character parts later in his career, and worked well into the 1960’s.

- I couldn’t really wedge it into the main article (somehow!), but I was impressed by how much of General Yen’s position was merely management. Comparing his role here to what Warren William does in something like Employee’s Entrance and you’ll see a stunning amount of similarities– though, of the two characters, it’s the Chinese warlord who refuses to stoop to rape!

- The Frank Capra fansite talks about the book’s ending (which is much different than the film’s) and how the film was tackled by Capra in desperation for an Oscar. Unsurprisingly, given that this film bombed (and at a million dollars was the most expensive thing Columbia Pictures put out that year, making it hard for it not to bomb), the film was shut out from that year’s contentions. However, luckily for Capra, he wouldn’t have to wait too much longer for an Oscar.

More from the behind the scenes short. That’s Capra in the center!

- FilmFanatic.Org offers an an excellent review of this one with some more good sources for you to check out.

- Here’s a DVD Beaver articles chock full of more screenshots.

- None other than Pauline Kael seems pretty okay with this movie. Look, I don’t get to namedrop critics you’ve heard of very often here, let me have this one.

- I sometimes give shit to Mordaunt Hall, the New York Times film critic in the early 1930’s which fit into the time frame of this website. And while he’s sometimes a wholly bad writer (“Jones has a number of really good lines, which Mr. Connolly speaks with his usual facility.”), he didn’t trot out a single racial slur or treat this movie with any extra criticism for its portrayal of miscegenation. His review, in fact, from the opening of Radio City Music Hall, strikes me as someone wholly intoxicated with the film, and it’s wonderful to see that come across.

And here’s the lovely Ms. Stanwyck for the road.

- Catching the Classics uses the movie to pay tribute to Barbara Stanwyck’s skill and Capra’s career. I thought this was a good observation:

Capra was a faithful subscriber to the belief of “The American Dream,” but what made him unique, what made him special, was the fact that he was smart enough to realize that dream, at times, could impose on the dreams of others, belittling their aspirations in the process.

- Richard von Busack has a good if short review in Metroactive. His final two lines struck me as exceptionally well written:

The movie is all about the exotic becoming domestic. The frightening idea of the Other—forbidding, inscrutable—dissolves in one of Capra’s rippling pools of images.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film appeared in the Wikipedia List of Pre-Code Films.

- This film is available in the Early Frank Capra Collection via Amazon and TCM, and can be rented from Classicflix.

|

|

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar!Home | All of Our Reviews | What is Pre-Code? |

19 Comments

lassothemovies · August 9, 2013 at 7:38 am

Well Danny, I’m not sure how you managed it, but I believe I love this film even more now than I did yesterday. Your depth and insights are incredible interesting and I highly enjoy reading your thoughts on this incredible picture.

Incidentally, “Shanghaied from Shanghai” is my favorite thing I have read all week.

Thanks again, and long live Capra and Stanwyck films!- Paul

Danny · August 9, 2013 at 10:18 am

Thanks for the kind words, Paul. I wrote ‘shanghaied from Shanghai’ in my notes and probably spent way longer than necessary trying to work that into a paragraph; glad it got some enjoyment!

Kimberly Garrison · August 9, 2013 at 11:26 am

I saw this movie about a year ago and saved it to my DVR. For this period it is so daring. This is one of my top 10 pre-codes. I remember after seeing it, I was speechless because the story was about a Chinese man kidnapping a white woman and the woman falling in love with him. Even 40 years ago this movie would have been controversial but for 1930’s wow.

Barbara Stanwyck was some actress between Baby Face and the Miracle Woman I have developed a true admiration for her for going outside the box and being controversial in her roles. Before I got into pre-codes I only remembered her from her Big Valley days when she was older. Now whenever I see a movie with her in it I have to watch. My favorite all time Pre-code star is Norma Shearer but Barbara is my strong second.

Danny I love your site and look forward to seeing the movies you review. Keep up the good work.

Danny · August 9, 2013 at 1:45 pm

Shearer, Stanwyck and Dietrich all do a really great job of sinking their teeth into nasty, complicated characters during this era and creating a number of masterworks. I think once 1935 rolled around they lost a bit of that ground– women lost a lot of their flaws in film as the stakes had been reduced for them so greatly. Stanwyck luckily regained some of that since she took on noir, one of the few other genres that let interesting women in until the 60s. It’s a shame, because who knows what could have happened to these actresses if not for that sudden right turn in firm censorship.

Thanks for the kind words, Kimberly. I appreciate them!

Judy · August 19, 2013 at 1:53 pm

I’ve only seen this once, but remember it as intensely powerful. Reading your in-depth review reminds me that I must see it again! Great work as always, Danny.

Danny · August 19, 2013 at 2:37 pm

Thanks Judy!

Lesley · September 29, 2013 at 5:54 pm

I’ve been thinking a lot about this one lately and was happy to find your review, which makes some interesting points and observations. Thoughtful and funny, too.. Most iinterested in the stuff about imperialism and the gospel. Thanks, Danny!

Danny · September 29, 2013 at 8:37 pm

My pleasure! Glad to help!

Michael · January 19, 2014 at 2:34 pm

I just saw this for the first time last night on a double bill with Lost Horizon, which made for an interesting evening. It was sort of a mini “kidnapped by Asians” film festival. I thought your write-up on Bitter Tea was very good and I particularly liked the half and half photo of Nils Asther. I just discovered you site and I’m looking forward to reading your other reviews.

Danny · January 23, 2014 at 8:42 pm

Thanks for coming by! This film is definitely one of my favorites.

Emily · July 17, 2014 at 1:37 pm

I saw this film for the fourth time tonight and every time I watch it, I love it even more. I especially love how human and ambiguous everyone is allowed to be.

Danny · July 18, 2014 at 12:13 am

Very much agreed. 🙂

Barbara · July 19, 2014 at 11:45 am

Thanks for the great review of one of my all-time favorite movies. I remember watching it as a child on TV on Million Dollar Movie in New York in the 50s. It stayed with me all of these years. I was delighted to see that it was on TCM last night. I do have one question: I have heard that the European version is uncut. Have you seen that version and is it any different?

Danny · July 20, 2014 at 9:14 am

Thanks for coming by. I’ve actually never heard of a European version before, but that does sound interesting. If I ever hear anything about it, I will definitely add something here. Thanks~

shadowsandsatin · June 8, 2015 at 7:50 pm

I still have yet to see this movie in its entirety, but I saw enough of it yesterday to come here looking for your review. I really enjoyed your insights (not to mention shanghaied from Shanghai!), and it inspired me to check out the whole thing.

Danny · June 11, 2015 at 1:56 pm

I hope you check it out Karen, and I hope you like it as much as I do!

Tony Paradise · August 4, 2016 at 7:12 am

The only thing I know about this film is, It was the first movie to play Radio City Music . It played a short while because of it’s subject matter.

Comments are closed.