|

|

|

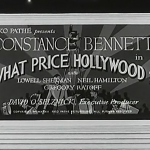

| Mary Evans Constance Bennett |

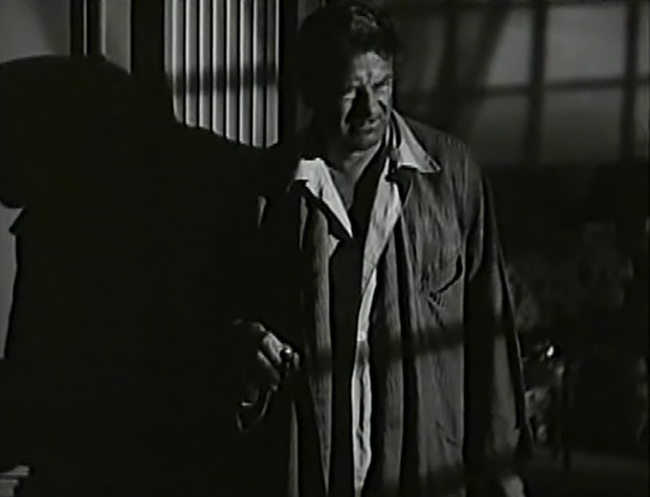

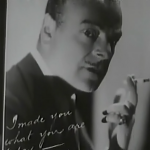

Max Carey Lowell Sherman |

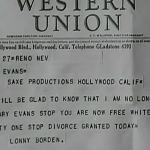

Lonny Borden Neil Hamilton |

| Released by RKO/Pathe | Directed by George Cukor Run time: 88 minutes |

||

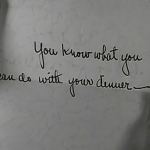

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- “You want me to call Nick over?”

“Sure. Tell him about that 17-year-old girl you put in pictures.”

- The tipsy Max bumps into a woman in a suit and asks who her tailor is.

- “You don’t give a WHAT?”

- A drunk man strikes a match on a statue’s posterior.

- Divorce and suicide.

What Price Hollywood?: Cheap and Vulgar

“Mr. Carey, I’m in pictures!”

“Well, don’t blame me.”

It’s not often you see a movie about how utterly mundane movie stardom is. What Price Hollywood? tantalizes the audience with a chance to look beyond their fan magazines and see how the ladder of success really works in Tinseltown. What we get instead are movie stars, directors and producers struggling to find something worthwhile, combating snobbery, and having great trouble simply pulling themselves together.

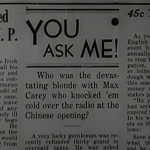

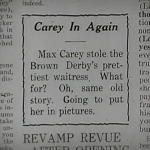

Constance Bennett leads the charge, oscillating in this film perfectly between her earlier tragic roles and her future as a great screwball comedienne. Here she’s an ambitious waitress named Mary who spends her afternoons gaping at Clark Gable in the magazines and at night she waits tables at the Brown Derby. She’s no wallflower waiting for a miracle, but actively seeking out stardom. She sees her opportunity when film director Max Carey (Lowell) stumbles in, a bit soused before a big film premiere. His date falls through, and Mary happily inserts herself in that place. The two develop an instant rapport and head to the premiere in a puttering old crank car that bellows smoke. Mary treats it like a star entrance, even adopting a mock English accent to keep the reporters on their toes.

She thinks she’s arrived, but Max gives her an audition. She stinks on camera. One note about this scene; Max, who we’ve only seen tipsy or hungover, is utterly professional on set, clearly knowing exactly what he wants. He can immediately see that Mary is doing it wrong, and, through him, the audience sees it too. This is also one of the few scenes in the film where Max is sober. Stuff gets to him.

Mary, who knows she’s in trouble, spends the entire night at her boarding house rehearsing and rehearsing her line (director George Cukor brilliantly showing this in shots of feet running up and down the stairs in montage) until she finally understands what Max wants. She shows up to the screening room to watch her triumph, only to be shooed away by the producer Julius Saxe (Gregory Ratoff). When she pops up on the screen, he instantly declares her a star; she has to shout from the projection booth to accept her accolades. Max, who’d been sitting behind Saxe in the screening room with his feet propped high, doesn’t even take a second for any sort of triumph. He knew it was gonna happen. Might as well in Hollywood.

After a nifty montage full of stars and sparkles and marquee signs bowing to the new sensation, we flash forward to Mary at the height of her fame as America’s Pal. Things take a turn for the interesting when she meets polo playing blue blood Lonnie (Hamilton). She’s told not to bother with him (“He’s strictly the breach of promise type.”), but she decides to mess with him after he mentions being sick of blonde starlets. She resists his charm, which infuriates him so much that he kidnaps her in the middle of the night and force feeds her caviar. It must be love!

Saxe, who spends most of the movie being Mary’s confidant, still manages his own moments of thoughtless brutality. Her wedding day, a culminating event at a crossroads of both her personal and professional life, goes awry when the crowd gathered outside of the church begins to claw at her gown for souvenirs. The couple is rushed back inside where Saxe crows, “We broke all the house records for this church!” But that sudden violation on the couple’s personal violation won’t be the last.

Max is more helpful at helping Mary navigate Hollywood, at least until he comes in the way of the happy couple as his drinking increases and his work dries up. Lonnie begins to resent his wife’s sympathies and the fact that she has a career– an immensely popular one at that. He can’t stand the game she plays with the press, stubbornly overlooking the silly rules that govern his own East Coast blue blood life. As Lonnie and Mary part, Max reappears after a long drinking spell. His alcoholism has gotten the best of him, and it’s begun to empty him out. His career is gone, and he can barely take a moment of life seriously. Mary is his only friend, and there seems that there’s only one thing left to him to do to help her.

Max can be read as a homosexual– certainly not beyond the realm of possibility that Cukor may have tweaked him that way– and much of the success of this version comes from the platonic relationship between Mary and Max. It’s one of playful respect, where he sees her ambition and elevates it while she sees his flaws and tries to comfort him. From the outside, it looks foul, especially with Lonnie brooding about.

What Price Hollywood? would serve as the basic building blocks for two very famous technicolor musical films, both named A Star is Born. What the latter films do, however, is condense Max and Lonnie into one character. The future Norman Maine inherits Lonnie’s temperament and romance plus Max’s depression and wit. But by combining the characters, you simplify the story, changing drama into melodrama and removing complexity for broad, colorful strokes. It’s not a flaw, but What Price feels more human; the Stars are engineered for tears.

But while Maine’s own flaws within himself bring about the trouble in the Star films, here the villain is a little more broadly drawn. Max is more a victim of his own jaundiced view of the world than having any motive to hurt anyone; once he finds he’s adding a net negative effect on the world, he does something about it. And while Lonnie is certainly a heel (magnified even moreso thanks to 1930s misogyny), it’s clear (his) upbringing and (her) ambition are what bring him into conflict with Mary. That doesn’t make him a villain, only thickheaded. And the movie certainly does a great job making you dislike Neil Hamilton (as all pre-Code films starring him must), he’s not the bad guy.

No. I’m afraid, dear readers, I’ve seen the villains of What Price Hollywood?, and they are us. The makers of the film, David O. Selznick and George Cukor (who together would turn out the sublime Little Women a year after this), didn’t turn the camera so much on Hollywood but on the audience themselves, both giving them a taste of the reality behind the motion pictures while dutifully chastising them for their twin needs of scandal and vulgarity. If the news media and vociferous public in this film didn’t have tunnel vision and need the relationship between Max and Mary defined in romantic terms, they may not have driven that wedge between Mary and Lonnie. And if they didn’t need scandal to satiate them, maybe Mary could have kept her career as her world falls apart around her.

Of course, this sort of of moralizing from film studios is laughable, the same as if bankers made a movie about being abused by poor old grandmas seeking extensions on loan payments. What softens the blow is how much of the film is dedicated to showcasing how much hard work goes into making films and surviving the cutthroat world of motion pictures. Take one sequence of Bennett performing a musical number on the set of the picture, shot in a typical approximation of a nightclub and even more typical approximation of how you’d see this filmed in 1932. Cukor deftly cuts away to the crew members working on the set during this number, from those in charge of lights to those doing sound and the crowd watching patiently. It helps perfectly puncture the illusion by using a very typical scene from movies of this era and breaking the audience’s expectations and reinforcing the strange disconnect between what we see on screen and reality.

The film making expertise doesn’t end there. The best scene in the movie for my money involves the main characters sitting poolside and arguing about the next movie proposal for Mary. The script is a bit of ridiculous dramatic fluff– in this picture she’s going to have a baby after getting married (which is also a funny nod to What Price Hollywood to boot)– but the producer, director and star all circle each other as they try to sort out what it will be and why. Even if it ends with Max pulling poor Louise Beavers into a pool (her singing isn’t that bad), it’s this scene that feels the most realistic and natural in the whole affair.

While it’s not the searing indictment of Hollywood you might expect, instead What Price Hollywood? offers you the chance for Hollywood to see things from their point of view. Sometimes dreams come true, but making that dream a reality is honest-to-goodness work. That work is a tight-rope act, where privacy and self interest can be seen as selfish and honor and friendship seen as scandalous. It may seem silly, and it may seem like fiction, but it must be true– I saw it in a movie.

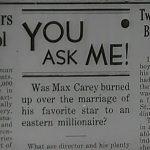

Gallery

Click to enlarge. All of my images are taken by me– please feel free to reuse with credit!

Trivia & Links

- This week’s entry is brought to you by the Classic Movie Blog Association’s Fall Blogathon, Hollywood on Hollywood. Be sure to check out the other entries here!

- The movie begins with Bennett impersonating Greta Garbo. The two would eventually star together in Garbo’s last film, Two-Faced Woman. Garbo would have many of Bennett’s scenes cut because the actress was upstaging her.

- “L.N.” in the New York Times is not a fan of this, which may be an understatement:

The Mayfair Theatre this week is just a bit of Hollywood in tired old New York. The footprints of the mighty are set in temporary concrete just outside, and from the screen there surges forth a message. […] Parts of “What Price Hollywood” are very amusing, intentionally, and others are despite themselves. Sections of it are very sorrowful, in the bewildered manner of a lost scenario writer, and yet others are quite agreeable. There is some good acting in the picture—much more, indeed, than it deserves.

- The Eclectic Screening Room is on a much different page, talking about the film’s balancing act between being what it satirizes and poking fun at itself.

This effort is irresistible. Not only is it an amusing look at how Tinseltown chews up and spits out its great talents, but it is also a glorious representation of the Hollywood schmaltz that it also satirizes.

- The Self-Styled Siren has a stirring appreciation for this one, going into its many in-jokes and appreciating the work put together by Cukor. This is my favorite passage:

But what a performance Sherman gives as Max. There’s no explanation for why he drinks; his one comment when told he should give it up is “What, and be bored all the time?” He doesn’t show contempt for his Hollywood trappings, but there’s something in Max that stands apart and mocks. The script gives Sherman a lot of lines that could play as nasty; Sherman speaks them in the deadpan manner of a man who long ago gave up hoping anyone was going to get his jokes. Mary does gets his point, all the time, and she tosses the verbal ball right back at him. That is reason enough to believe that he would take her to heart. When Max is viewing rushes of Mary with the producer Julius Saxe (Gregory Ratoff, and you won’t believe how young he looks), the director is so sure of his judgment that he lounges back in his seat until his face disappears, feet propped up in front of him. And Sherman gives you every nuanced reaction you could want with just the soles of his shoes.

- Cinepassion talks about how the film influenced so many others:

At one point, Bennett is pushed through a crowd as frantic fans snatch pieces off her dress, and it’s like a Nathanael West note inserted into a F. Scott Fitzgerald novella; at another, Cukor goes cannily yet unfussily meta by splintering the spectacle of the star singing in a café into shards of studio technique (the cranking of the camera, the maneuvering of the spotlight, the adjustments of the microphone). Wandering in and out of the main plot (and spiking it with welcome vinegar with each appearance) is Sherman’s crumbling filmmaker, who leaves the world via a fabulous Slavko Vorkapich montage, an accelerating whirlpool of split-second pictures capped by a startling soupçon of slow-mo. The various versions of A Star Is Born are just the most immediate remakes, The Bad and the Beautiful, Inside Daisy Clover, Le Mépris and others flow from it.

- Immortal Ephemera calls this ‘the cream of the crop’ for pre-Code films on Hollywood, and has plenty of extra background info:

“Suggest sensational comeback for Clara Bow in a Hollywood picture titled The Truth About Hollywood,” David O. Selznick wired his bosses in New York in early March 1932. They weren’t very keen on the idea, and apparently Bow wasn’t either. Selznick got his way with the studio, then made plans for William A. Seiter to direct Helen Twelvetrees in his inside-Hollywood film. That changed fast. Twelvetrees was busy in State’s Attorney and RKO soon discovered she was pregnant—she was shifted to a less demanding role in Is My Face Red?, directed by Seiter. Next, RKO announced that they’d seek out a young, unknown actress for the lead, but before the calendar turned to April Selznick had borrowed director George Cukor from Paramount and cast another of RKO’s top properties, Constance Bennett, in the leading role. Joel McCrea was originally cast opposite Bennett, reuniting the pair from The Common Law and Born to Love (both 1931), but Neil Hamilton was ultimately cast as Lonny. Bennett and Hamilton would also work together in their next film, Two Against the World, while Bennett wound up paired twice more with McCrea soon after, in Rockabye (1932) and Bed of Roses (1933).

- Here’s a preview clip of the movie from Warner Archive:

Awards, Accolades & Availability

More Pre-Code to Explore

7 Comments

Dulcy Freeman · October 21, 2016 at 2:47 am

I wish you’d write more about Lowell Sherman, both as actor and director. The quote, from Self-styled Siren, “…a man who long ago gave up hoping anyone was going to get his jokes…” is so apt! One of my special favorites!

claudia mastro · October 21, 2016 at 5:36 pm

i love this movie!! was a present from a friend of mine! i couldn t believe it was from 1932. seemed so old yet so new. it was refreshing wit hot air, you know wat i mean? the relationship between mary and the director was so modern, yet the realtionship with his husband was so old. a masterpiece

Patricia Nolan-Hall (@CaftanWoman) · October 21, 2016 at 10:00 pm

Wonderful insights and a perfect summation of a movie that continually entertains. It was my introduction to Lowell Sherman, and could there be a better one?

Silver Screenings · October 22, 2016 at 4:14 am

I didn’t realize there would be so many “Hollywood on Hollywood” movies that I haven’t seen, and this is one of them. Thanks for the tip re: streaming on Amazon. I’m really looking forward to it.

Also, thanks for organizing this blogathon. I’ve learned a lot from all these terrific essays.

Marsha Collock · October 23, 2016 at 10:31 am

Great review, Danny. I happen to like this film a lot, mainly because of Lowell Sherman’s grand performance and the steady, and chic presence of Constance Bennett. Not exactly “A Star is Born,” but pretty good stuff. And many, many thanks for doing the heavy lifting on the blogathon!

Jocelyn · October 23, 2016 at 9:00 pm

I’m glad you chose to write about this one–I’m not a fan of A STAR IS BORN–any version, and do like pre-codes, so I have to check it out. I may appreciate Constance Bennett more as well. Sounds like a good, 3-dimensional role for her.

BlondeAtTheFilm · October 25, 2016 at 12:44 am

Wonderful review! I always enjoy Constance Bennett and need to watch this movie. I especially liked your examination of the “villains” in the picture. Always interesting when Hollywood turns the lens on itself and its audience! Thanks for a great post and for your work on the blogathon!

Comments are closed.