|

|

|

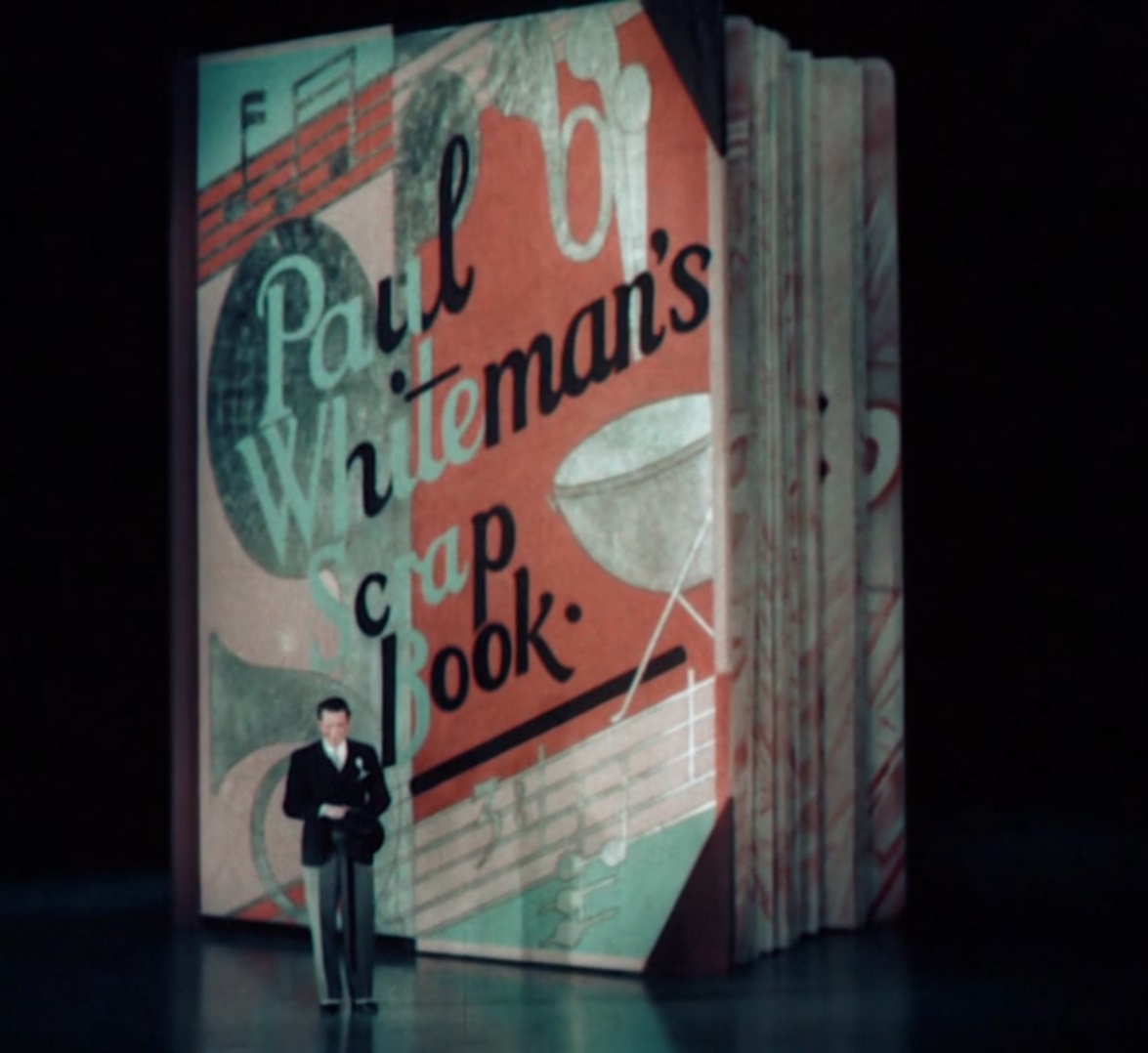

| Paul Whiteman |

John Boles |

Laura La Plante |

| Released by Universal Directed by John Murray Anderson Run time: 99 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- There are a few mildly racy sketches, like one where an adulterer hides in the closet when the husband returns home.

King of Jazz: Happy Feet

“Jazz was born in the African jungle with the beating of the voodoo drums!”

This is probably going to be one of my stranger reviews, but, thankfully, King of Jazz is one of the stranger movies I’ve touched on for this site.

As the talkie era kicked off in earnest in the late 1920s, there were a variety of… variety musicals that hit the screens. Paramount on Parade I’ve touched on here, while others like Show of Shows and Hollywood Revue of 1929 are just a tad outside this site’s purview. All of these were large, expensive musicals that showcased these studios, their slate of stars, and the proficiency of their soundmen.

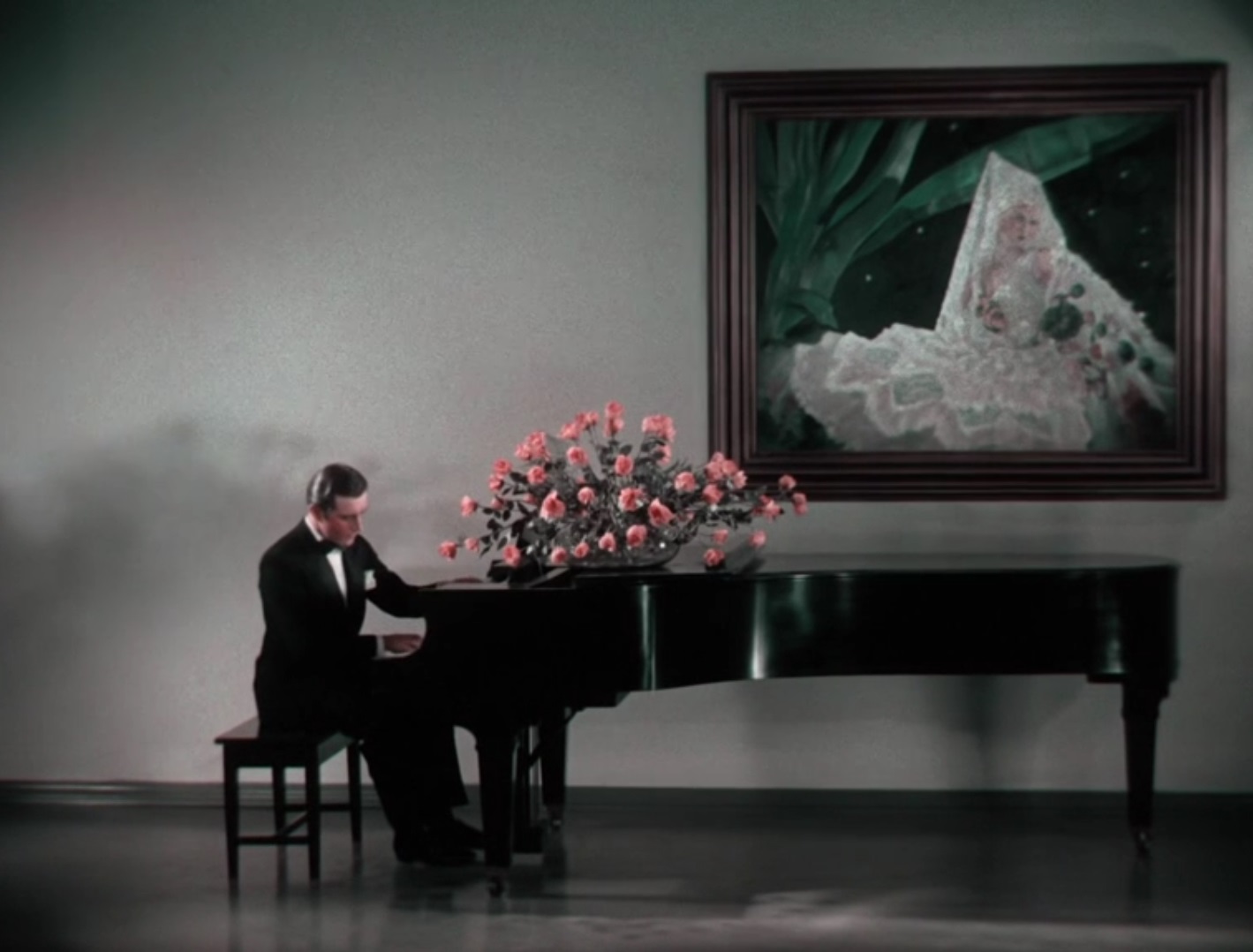

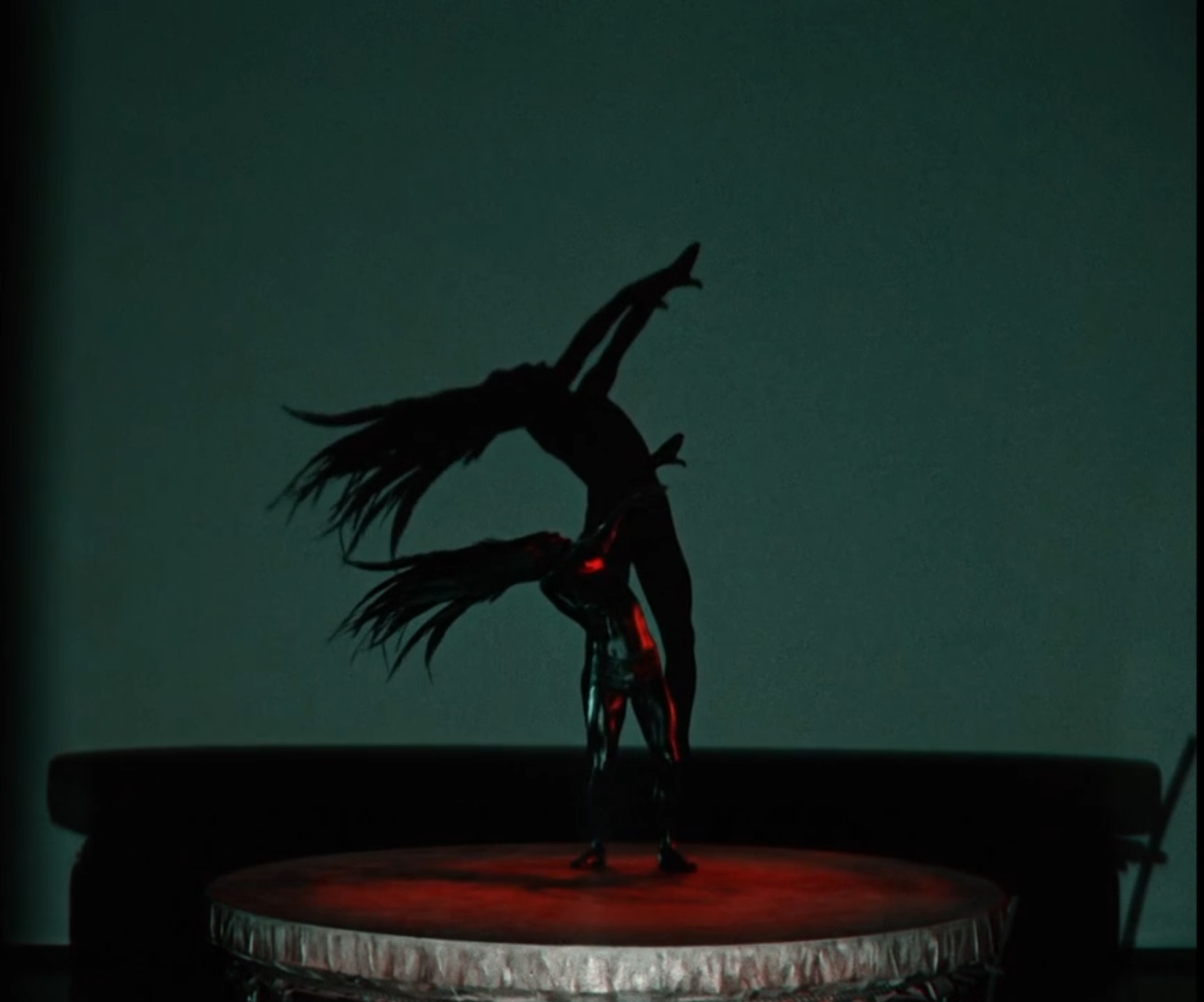

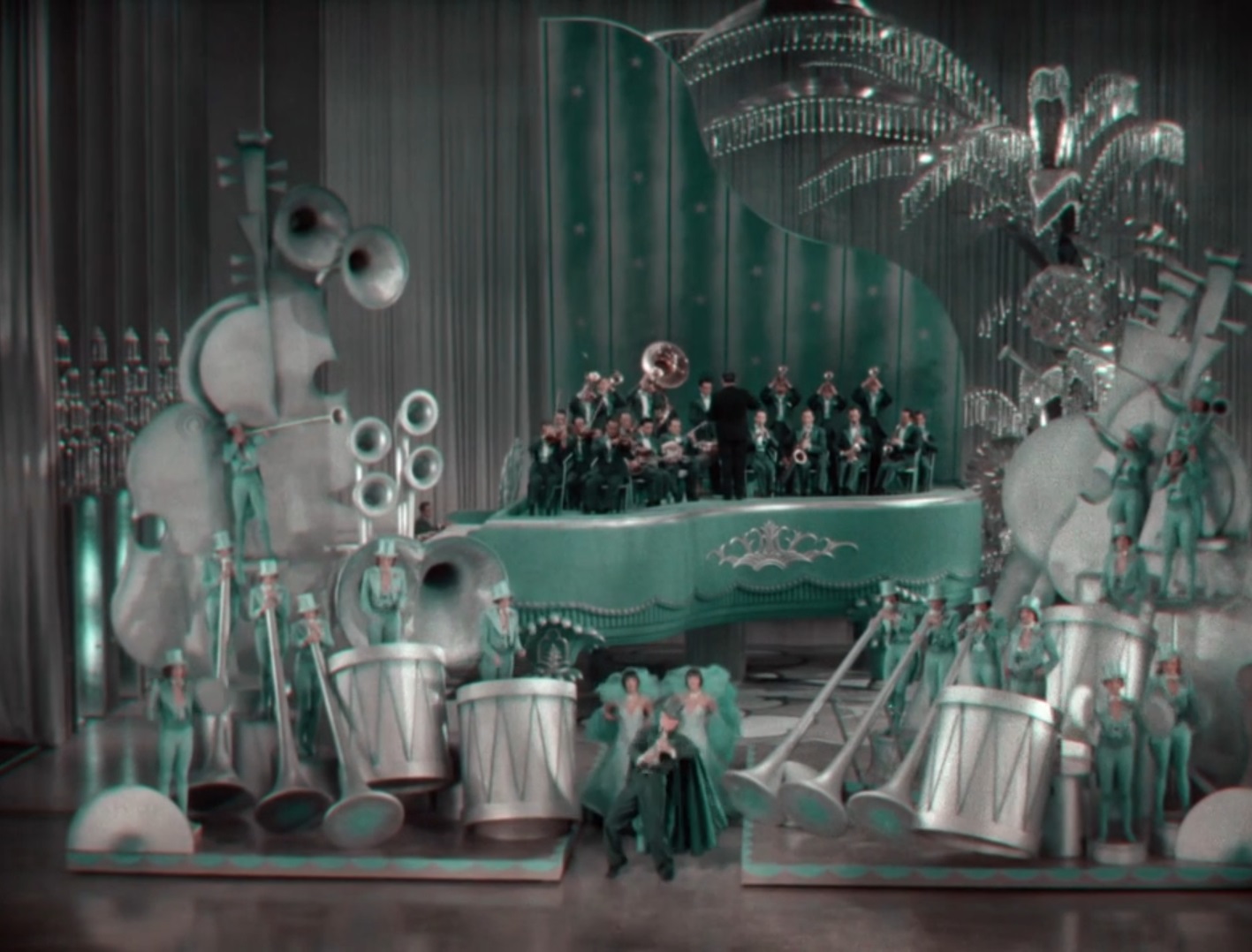

King of Jazz takes the same tack, but instead of focusing Universal’s lineup of stars (which, at this time, wasn’t anything to really crow about) but instead spending lavishly on beautiful two-color technicolor and trading in on the trendiness of jazz music. Filmed in a variety of greens, silvers, reds and nary a blue in sight, the film is a ramshackle but gorgeous postcard to a musical era– or at least one perspective on it.

Primarily recounting the era as seen through predominately white eyes, only partial mentions of the music’s origins in black America are nodded at, including one cute (if odd– never underestimate this film’s ability to be odd) moment where various band members are canoodling in the park with beautiful chorines while Whiteman’s partner is a little Black girl who tweaks his mustache. That’s cute, but the film also takes pains to illustrate the Black contribution to jazz music as deriving from “the voodoo drums of Africa” and trailing off suggestively, minimizing it in order to elevate Whiteman’s music which isn’t… you know… jazz.

I’m not a music critic, nor much of a music listener. (Lo-fi beats are my jam!) Instead, here’s an excerpt from Farran Smith Nehme’s essay “Now You Has King of Jazz” that covers the eternal debate on whether or not ‘The King of Jazz’ actually played jazz music:

Meanwhile, though Whiteman frequented Harlem clubs and counted Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and Eubie Blake as friends, music scholars still debate whether what the man known as King of Jazz played was actually jazz. He limited improvisation and arranged his numbers in the style he preferred. “I could never understand why jazz had to be a haphazard thing,” he said. When the movie was made, Whiteman’s style of what he called “symphonic jazz” was at its height: he offered syncopated dance music, popular songs given the orchestral treatment, and orchestral music lightly jazzed up. Whiteman is a classic example of the mainstreaming of something that began as edgy, bohemian, and black. When his orchestra played Paris in 1926, one American journalist wrote earnestly, “It is to be hoped that all French and other misguided jazz-players will go to hear Mr. Whiteman, and learn that jazz is not a riot of noise but something much more insinuating and subtle.” In later years, that kind of praise would sound damning. Whiteman, however, filled his band with talented jazz musicians and paid them high salaries.

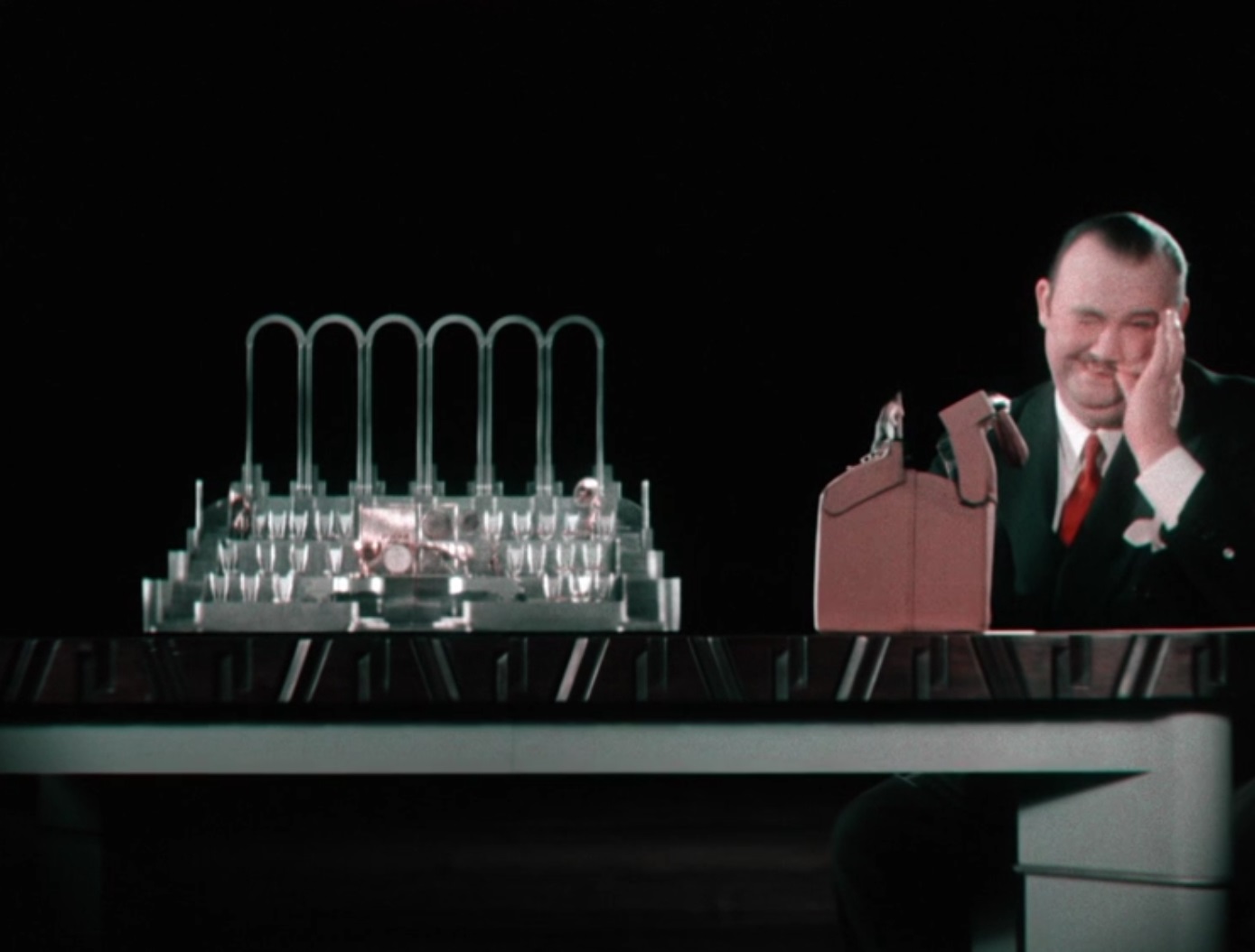

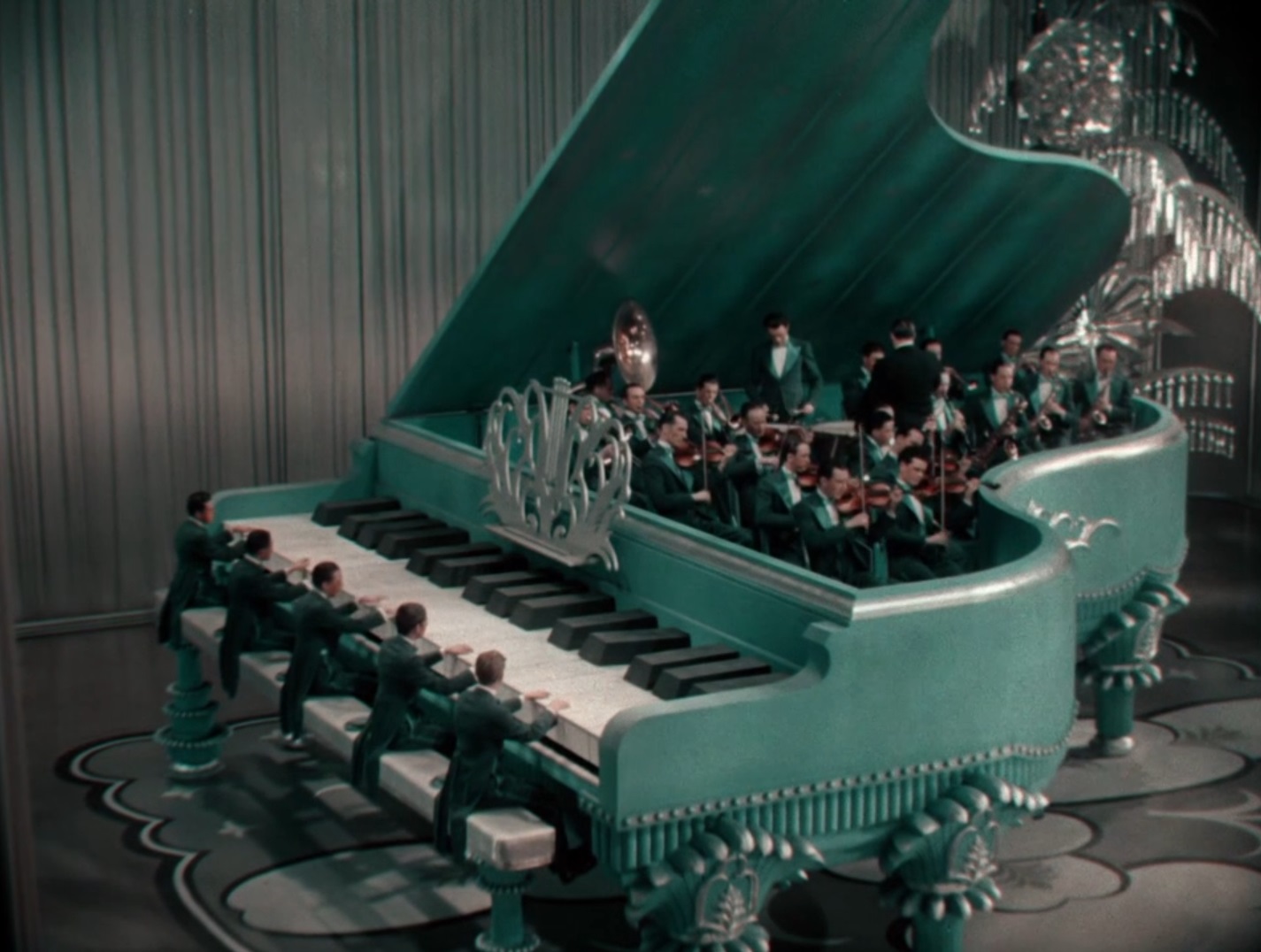

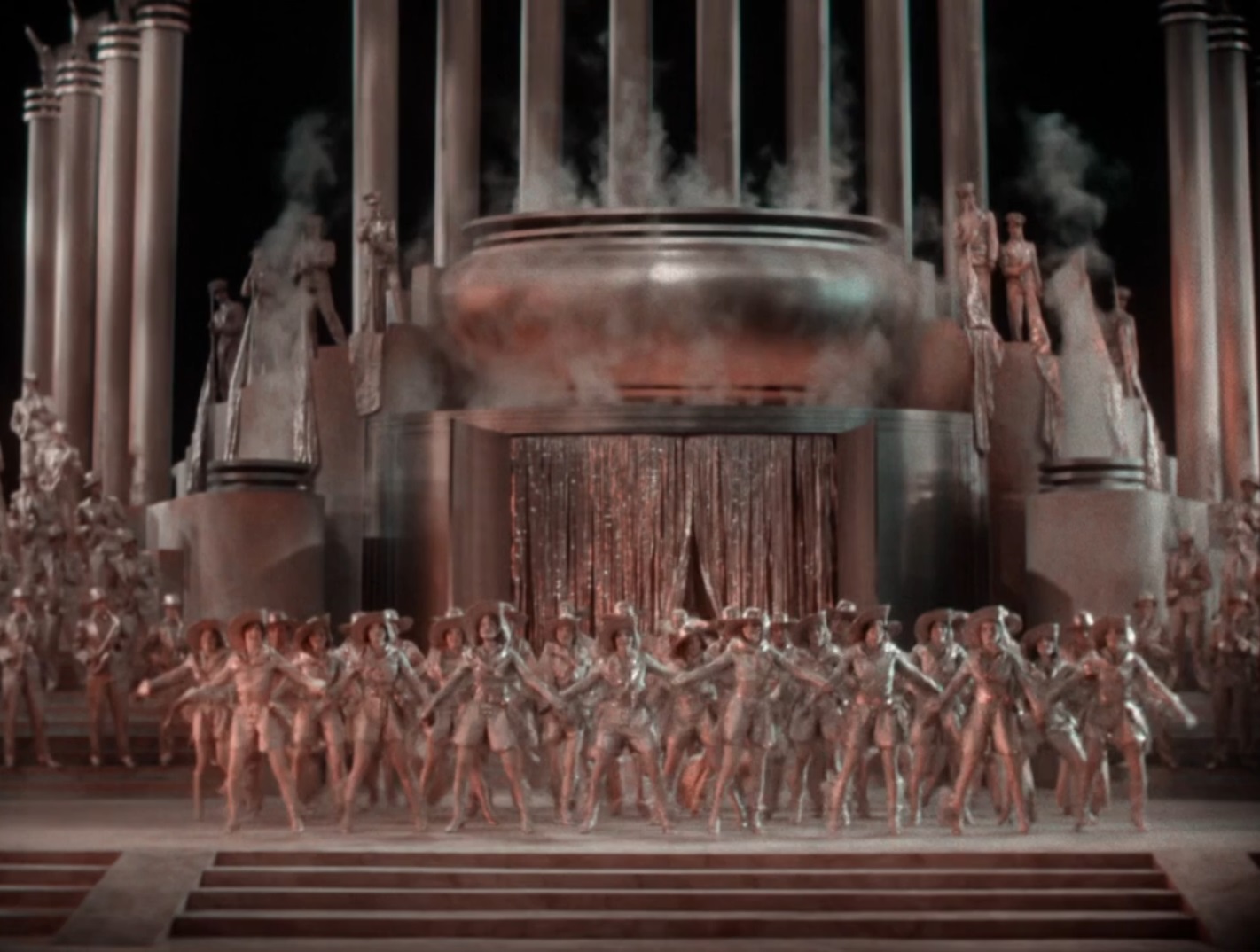

What saves the film musically are a pair of elaborate numbers. First is a dazzling staging of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” set on a massive grand piano with a dozen men sitting at the oversized keys while Whiteman’s orcheastra expounds from up top. Second is a trippy production of “Happy Feet” which follows the legs of a set of smiling chorus girls with the precise fetishism of a Busby Berkeley. This number is sung by the Rhythm Boys which include a pre-fame Bing Crosby, looking, as all of the performers do, slightly pink.

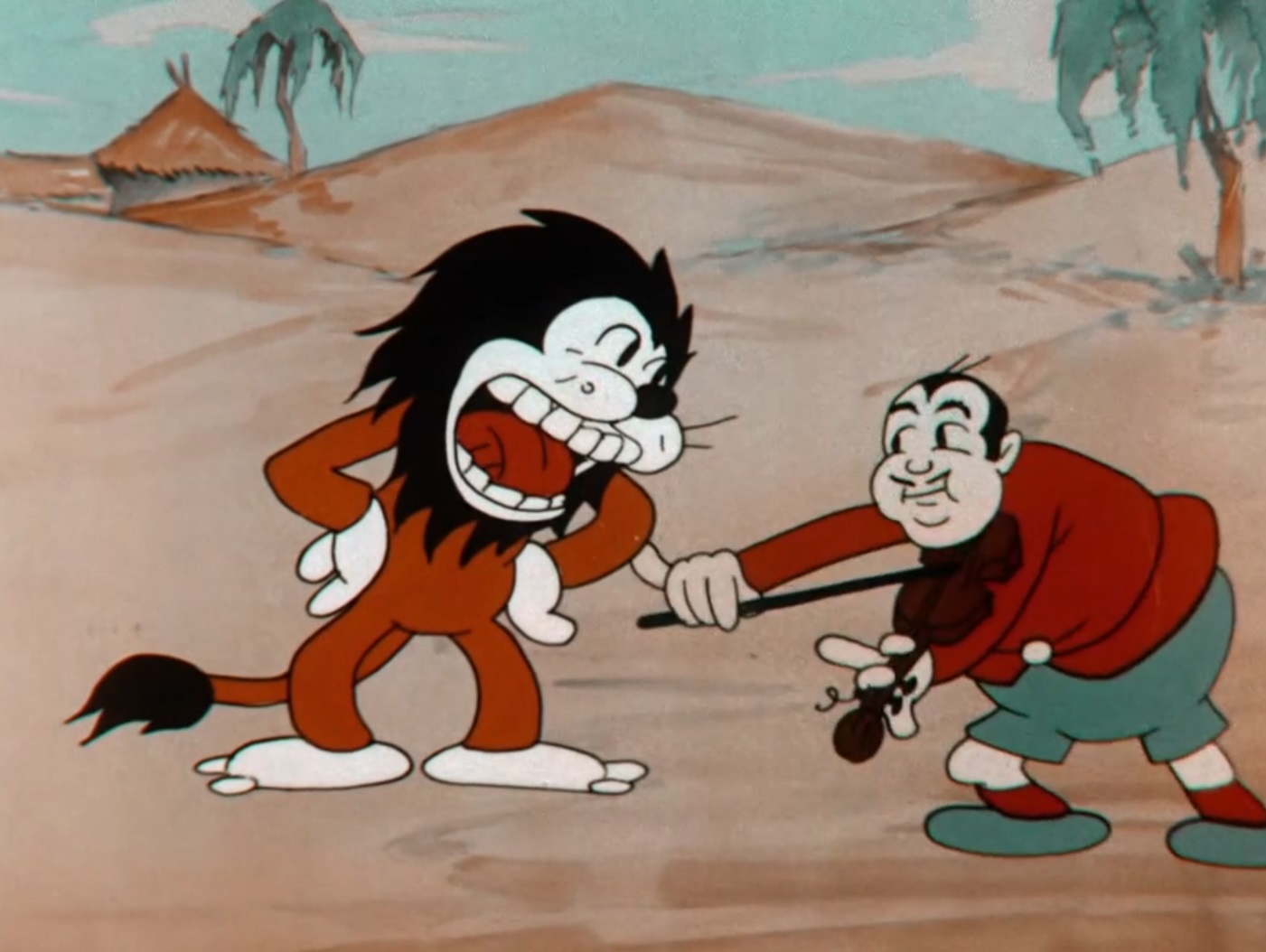

Otherwise, many of the sketches are one note, with an early animated sequence– the first in Technicolor– being particularly bland. Other numbers, including an elaborate wedding march, are more odes to spectacle than instilling any wonder in the audience. While Whiteman is kind of charming, John Boles gets a pair of crooning numbers that left me cold, and some of the humor in this film wouldn’t fly on a Bazooka Joe wrapper.

Overall, King of Jazz is a curio, probably worth at least one watch to drink in its more impressive parts as well as enjoy the gorgeous eeriness of two-color Technicolor. While the movie may or may not be the whitest film about jazz ever made, it is certainly the most aquamarine. It can be appreciated as the ultimate evolution of a kind of film that was out of style before it was made, the apex of the plotless musical revue pictures that so briefly captivated the world, and as the kind of movie we will certainly never, ever see anything like ever again.

Screen Capture Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- Produced by Universal at the expense of $2 million dollars (at a time when lavish A-pictures at MGM were probably at most $500k), the film spent years being made and came out on the tail end of the revue craze. It was a huge flop. Produced by a young Carl Laemmle Jr., still in his 20s, the production may have sunk the entire studio had he also not invested in a pair of the 1930 hits, All Quiet on the Western Front and Dracula.

- Rather unusually for one of the film’s I’ve covered, King of Jazz actually has a full, beautifully illustrated book solely about it. King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue by James Layton and David Pierce is available and a definitive document on the film’s production, rescue and restoration. I actually do not own this book and thus can’t pull any trivia from it, so I recommend you get it and prove yourself smarter than me!

- The New York Times has hit the movie twice, with its original review from Mordaunt Hall enthusiastically recommending the film, noting, King of Jazz is “one of the very few pictures in which there is no catering to the unsophisticated mentality, for all the widely different features are of a high order and yet one can readily presume that they will appeal to all types of audiences.” In a 2016 re-appreciation, J. Hoberman delves into the film as a rehabilitation of Carl Laemmle Jr.’s reputation and the dearth of effort it took to restore and present King of Jazz once more.

- As per the AFI, the film was one of a number of early sound films that had multiple versions made in various languages. The introductions would be interchanged with footage of celebrities of other nations for the local release, the comedic sketches were dropped, and the numbers presented in English with their lavish choreography intact. There existed German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese and Czech versions, with a possible Hungarian version rumored to have a pre-Dracula Bela Lugosi as the master of ceremonies.

- A pre-remaster and detailed review from Bright Lights delves into the film before it was widely available on video and has a lot of great details about Whiteman that I hadn’t seen anywhere else, including the fact that his records sold in the 1920s at about a 1:1 ratio to record players.

- As I lack the ability to get blu-ray screenshots, you should check out some of the beauts over at DVD Beaver.

- The contemporaneous Harrison Reports noted that the picture, “drags considerably.”

- Variety is pretty cold on the film as well, though, amusingly, they bash the staging on “Rhapsody in Blue”, just about one of the few things that still impresses.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film won an Academy Award for Best Art Direction.

More Pre-Code to Explore

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 Comment

Rift Corbitt · August 26, 2021 at 11:31 am

As I recall two-color Technicolor was not capable of reproducing true blues. The Sea foam greens you see in reality were actually blue.

I very much recommend this book:

https://www.amazon.com/King-Jazz-Whitemans-Technicolor-Revue/dp/0997380101

Comments are closed.