Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Nora is called, “a common cheap hooker,” which is surprisingly blunt for the time.

- Nora goes through a lot of misfortunes, not the least of which is a rape that transforms her life.

- “Damn” or “Dammit” is muttered several times.

- Moran becomes a kept woman.

- … Suicide?

The Sin of Nora Moran: Of Shattered Souls

“I have a plan, if you’ll only leave and trust me. Can’t you understand why I’m asking you to do this? […] It’s me. The months we’ve spent together. They’ll take those months from us and spread them across the front page of every newspaper. They’ll make them ugly and cheap, instead of what they were. I’m not asking you to be cowardly. I’m asking you to let me keep the only happiness I’ve ever known. You’ll go, won’t you?”

Nora Moran is a hard luck case. An orphan, she was adopted by a good family but left on her own after a gruesome car wreck. She eagerly tries to make it as a dancer, but only finds rejection and loneliness. She joins a circus to help out a lion wrestler (who really wails on the lions) and is happy for a year until she’s drunkenly raped by him. She joins a chorus line back in New York where she meets Crawford, a soft spoken man who takes her in and gets her her own house over the state line. That latter half is important because Crawford is running for governor, and must keep their affair a secret. When the past comes back in full force, Nora must go to the electric chair to save everything she knows and loves.

It’s a pretty common melodramatic storyline (in fact, I spent much of the movie being reminded of the star-studded and more straightforward Manhattan Melodrama), but the way that Nora Moran is told is remarkably unconventional. Three narrative strands that all propel things forward, obfuscating as well as illuminating, each layer allowing us to see different sides of Nora and the mystery that surrounds her. The first is the framing narrative, with district attorney John Grant explaining to his sister and the governor’s wife Edith why she shouldn’t rush to confront him about some unsigned love letters.

The story begins with Grant challenging Edith to listen to his story. In one of the signs that we’re in for a treat, Edith is given a few seconds to consider this, and reluctantly takes a seat. Grant immediately sets a challenge upon her, his urge to overwhelm her with empathy beginning straight from the start.

“You said you wanted her to suffer. Did you ever witness an execution?”

“Why, of course not.”

“Did you ever see the preparation for one? The cold-blooded preparation for the disposable, burned out, lifeless thing that a few moments before the execution was a human being…”

He tells the story of the time Nora Moran spent in prison, and through her perspective we’re treated to her life story, told out of order and sometimes even breaking as she violently tries to resist the fate that’s coming at the end of her story. These layers add complications to the story, as we’re getting Nora’s story from Grant’s perspective, a man who eventually has no choice but to send her to the electric chair to protect his own greed and propriety. It turns Nora Moran from conventionality, making it the story of one man coming to terms with his guilt as well as one poor woman whose entire life of misery seems to have been wasted by cruel, masculine forces beyond her control.

The movie itself edited like jazz, with refinements reconfiguring themselves in loops. Besides a remarkably fluid camera, the film is absolutely kaleidoscopic. Goldstone exploits stock footage to create dizzying montages that take us through years, both forwards and backwards. There’s also constant cutting to the image of a fireplace, used to represent life itself in many ways as it both plagues Nora and consumes her for her titular sin whole.

Rare for 1933, the film is backed by a constant music score. Admittedly, it can sound pretty forced, especially early on. Filmmakers were still figuring how background music worked at this point, and even if it feels canned or even soap-opera-y at several points, but it never, ever lets up. As much as the editing, it’s the drumbeat of doom towards a dizzying and inevitable fate.

One of my favorite moments figures directly into this momentum, as Nora is caught up in her whirlwind romance with Crawford. So overcome with love, she happily recounts the length of their courtship: one week or seven days, seven nights. Each girl in line, as hardbitten as the next, asserts that there are fewer days in the week. Now it’s six days and six nights. Five. Four. Three. Two. One. “The week’s gone,” sighs the last girl in line. Goldstone uses a tracking shot here, pulling us along with the momentum of the conversation, but also zipping us through time, as the days disappear. Time is always doing that to poor Nora, and in one brief, wholly visual moment, Goldstone encapsulates the way the narrative won’t let her escape her own destiny.

Spoilers.

The final scenes unwind with Crawford alone in his office the night of Nora’s execution. Through flashbacks, it’s revealed that he was actually Paulino’s killer, and Nora will take the rap for him in order to keep their love affair quiet. She begs to let him do it, and even appears as an apparition in his office, begging for him to stay strong. But he can’t, and when it almost seems like he’s ready to do the right thing, Grant’s voice echoes through his head, urging him to think of his career. He begs for Nora to ignore it, but like Peter betraying Jesus, it’s obvious that for all of the love that he has, he’s still internalized his brother-in-law’s ambitious desires.

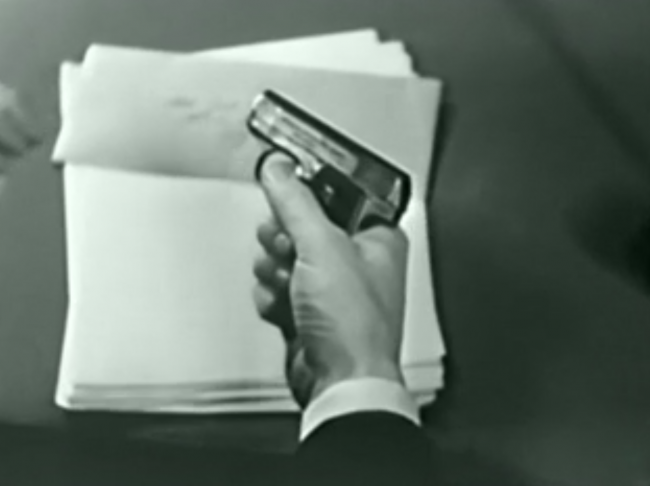

Crawford finally overcomes his cowardice of losing his position and the scandal that will ensue just when the clock strikes. He tries to call, but the line’s dead. It’s too late. He writes one last letter and pulls a small pistol out of the desk.

The use of first person here– well, slightly to the right of first person– is a fascinating decision. It’s not Crawford’s perspective, so is it Nora’s, standing over his shoulder and watching his final moments? Or is it Grant’s, the narrator and manipulator, picturing himself seeing the results of his handiwork in the most intimate way?

So much of the movie is tainted by Grant being the narrator, filtering this tragic story through a cacophony of his own inner turmoil and how the simple knowledge of how he sacrificed an innocent woman to save Crawford, an embodiment of his own ambitions and manipulations. Both Crawford and Paulino come across as ciphers in many ways, figments of Nora’s fevered imagination and idealized as either a monster or a hero. But that’s how Grant sees it, too. It’s Nora whose dynamism haunts him.

We see the gun put to his head and hear the body crumple, but what really happened? If Crawford killed himself, was this really the most appropriate way for Grant to tell his wife Edith? Answer: no, not at all. Or is the way the letter trailed off just Grant defining Crawford’s love dying being the same as a suicide, that his choice to listen to his demons killed him spiritually?

Who can say. “It’s over now,” frowns Grant in his final lines. “Or maybe it’s just the beginning.” They burn the letters and documents– all of them– and return to their comfortable, stable lives, knowing that it’s all theirs at the low cost of one, sweet, innocent girl.

End spoilers.

Zita Johann has a chipmunk face and an odd looking body– kind of a svelte Helena Bonham Carter of sorts. I know that’s not nice to say, but it factors heavily into building audience sympathy for her– we certainly wouldn’t buy the movie if it happened to Myrna Loy or Miriam Hopkins. There’s something inherently sad built into Zohann, a melancholy that permeates her appearance, so the brief moments of happiness that happen to her are doubly effective. Her tears when she proclaims, “It’s so lovely to have a house with things that work.” is simply heartbreaking.

The Sin of Nora Moran is a remarkable little gem, an oft told story filmed with urgency and care, and deeply sympathetic to the horrible cards dealt to the women of the early 30s. It’s remarkably ambitious, coming from a poverty row studio or not, and is well worth a watch for any intelligent film fan.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- Originally titled The Woman in the Chair and retitled for re-release as Voice from the Grave.

- The TCMDB article notes talk about how the film was viewed as derivative of another film:

Reviewers commented that this film borrowed the technique of “narratage” from the Fox production, The Power and the Glory, produced by Jesse L. Lasky, directed by William K. Howard and written by Preston Sturges, which was released earlier in 1933. The term “narratage” was coined by the Fox publicity department to describe the technique that Sturges used of telling his story in a series of flashbacks, some of which were narrated, that were not arranged in chronological order. New York Times, in comparing the two films, echoes other reviews in commenting that The Sin of Nora Moran “lacks the clarity, the efficient acting and the good writing of the Jesse Lasky production.”

- The great John D’Amico covered this on Homages, Ripoffs and Coincidences covered this as part of his look at poverty row studios.

Poor Nora Moran’s sin is being in love, though she also has the temerity to be trusting, innocent, and a woman in a society which disdains them. Like her spiritual sister Caddy Compson, Nora Moran is an oasis of good in a wretched world – a world so ugly that even our relatively compassionate narrator describes quite unashamedly how he “groomed” his brother-in-law to “further [his] own political power.” We learn in the first few minutes that Nora is the first woman sentenced to death in her state in 20 years and then, in a backwards structure that Citizen Kane would copy almost verbatim, we learn why. It’s a sad and painful story, enhanced by Zita Johann’s aching vulnerability. This performance is a career high. There’s a moment when she paces around listening to the official charges which calls to mind Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc.

- Cliff at Immortal Ephemera is a fierce advocate for the movie, and even wrote an expanded article about it in his book on pre-Code cinema.

It’s a Poverty Row film made by Phil Goldstone at Majestic Pictures for release in late 1933. In an unusual twist, studio owner and lead producer Goldstone also directed The Sin of Nora Moran. It is a public domain title that I picked up for under $4.00 during an Alpha Video sale, but you can even see it for free online. Despite this easy access The Sin of Nora Moran has somehow only accumulated just over 160 IMDb ratings at the time of this writing. We need to grow that number.

- Kristina at Speakeasy really enjoyed the star’s turn in the picture:

A few months ago when I saw The Mummy at the cinema, the conversation turned to what other movies Zita Johann was known for, and we couldn’t name any. In the Mummy she’s unforgettable for the wide-eyed, exotic look that has to convincingly put her at the peak of stylishness and beauty in eras centuries apart. But that seemed more a matter of her bone structure and certainly didn’t prepare me for the great acting she does as Nora Moran. She gets a range of emotions to play: hopelessness and despair as she waits on death row, terror as she realizes her rapist is back in town, nobility as she lies to protect her lover, and saintliness when she appears to him as he agonizes over the decision to pardon her. She’s a tough dame full of attitude when she’s arrested for murder, a sweet girl in love, and a helpless victim of a brute, and Johann does a remarkable job with all of those aspects. She most effectively conveys the madness of the condemned woman who eventually stops struggling and comes to accept that she was meant for a different kind of destiny and happiness.

- Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings enjoyed this one a lot.

- David Boardwell uses this film as an example in his history of the flashback.

- The Henry B. Walthall Film Reviews gave this a ‘B’ (both as a grade and in terms of ‘Walthall Factor’)

The acting seems strangely unemotional considering the plot of the film or, perhaps, that was the point. Some of the conversations in the flashbacks indicate that the characters have been reliving the story again and again. Perhaps they are now devoid of most of their previous feelings.

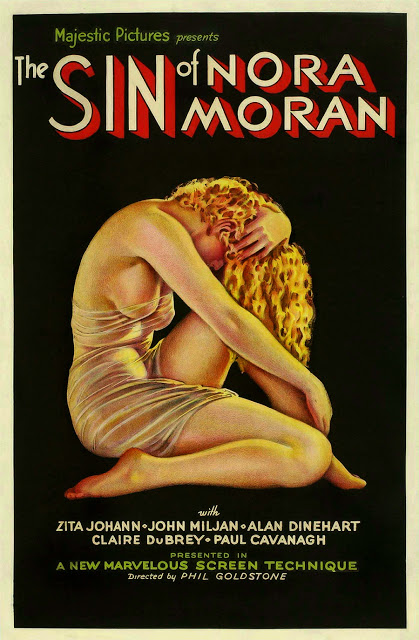

- If you’ve heard of this movie before, odds are good it’s because of its famous poster by Alberto Vargas. (You can read about Vargas’ life here as well as see other examples of his NWS work.) This is doubly funny since the woman on the poster looks nothing like Zita Johann, but whatevs. The poster is beautifully composed, with the title hanging heavy over the scantily clad woman hiding her face. It’s very evocative for sure. Cin*Eater talks about its infamy and tries to improve upon it.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is in the public domain, which means you can buy the Alpha Video DVD at Amazon or just click over to Archive.org or YouTube to catch it.

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 Comments

Cliff Aliperti · September 4, 2015 at 4:52 am

Entering with zero buildup, no foreknowledge, completely by chance, I didn’t expect much more than I got out of the other crappy ’30s indie titles I’d picked up from Alpha Video at that time. And I don’t think any other movie ever provided a more pleasant surprise.

Thanks for the links. This was one of the latest entries to the blog before the eBook, so I didn’t change too much. In other words, the free version works on this particular title.

maxofdimitrios · September 4, 2015 at 11:56 am

Cliff… Several years ago (1990’s) at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel I auctioned off an original poster as you show of THE SIN OF NORA MORAN. I recall a comment made afterwards that was probably on target: “The poster brought in more money than the movie receipts ever did”. It remains one of the more memorable posters I ever took bids for in a movie memorabilia auction. Still a beautiful and most provocative piece of art. Thanks for the article on Zita Johann. She was unique and special in her physical looks.

maxofdimitrios · September 4, 2015 at 11:59 am

OOPS! Sorry Danny. You deserve the recognition for all the info on Zita Johann and THE SIN OF NORA MORAN. My apologies. Cliff… get you next time.

Danny · January 7, 2016 at 1:16 pm

Ha, it’s okay. And that’s a good story, too!

Judy · September 9, 2015 at 12:47 am

Interesting that both this and The Power and the Glory had that complex flashback structure before Citizen Cane. I remember enjoying this film a lot. Enjoyed your piece, as always.

Judy · September 9, 2015 at 6:06 pm

Oops, I meant Citizen Kane. That will teach me to post in the middle of the night.

Dulcy Freeman · April 14, 2017 at 9:18 am

Just viewed the Alpha Video of this film and was pleasantly surprised at the quality of picture and sound, having had poor experiences with other titles. That said, I think this film astounding; it starts off slowly, even awkwardly, causing you to think “oh, no, it really is a cheapie from a cheapie studio” (despite the allure of Paul Cavanaugh and John Miljan in the same picture: be still my heart!). Then it builds and builds with splendid narrative economy, clever psychology, and spot-on visuals that draw you in to Nora’s growing dreamscape as she searches for a meaningful purpose to her life, finding the honor and dignity in dying that she never quite achieved in living. My favorite scene is where her landlady appears, seated by Nora’s cot in the prison cell, not wanting have given Nora the money that she did give, hoping that by not giving it, in this recreation of Nora’s life, she will be able to somehow change its outcome. Nora protests: she has to have the money, because it ultimately brings her love and meaning. The screenwriters crafted a superb tale out of bare-bones tawdriness, truly a must-see movie!

Dulcy Freeman · April 16, 2017 at 7:58 am

Mistake: not a landlady appearing by Nora’s cot; a friend from the circus.

Marilyn · June 2, 2020 at 8:20 am

“The Sin of Nora Moran” made its premiere on TCM on 5/3/20.

Comments are closed.