|

|

|

| Niki Maurice Chevalier |

Franzi Claudette Colbert |

Anna Miriam Hopkins |

| Released by Paramount Pictures | Directed By Ernst Lubitsch |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- “We are not afraid to skirmish in the dark…”

- One of Niki’s friends wants his permission to cheat on his wife. “You’re crazy about a girl and you don’t know what to do.” “Right.” “Then don’t do it!”

- When invited to stay for breakfast after a late night make out session, Franzi replies, “First tea, then dinner, and then maybe… maybe breakfast.” She does not make it to tea or dinner first.

- There are more euphemisms for sex in this movie than you could throw a euphemistic shoe at.

- Movie nerds who buy into the ‘Claudette Colbert was a secret lesbian’ theory will find plenty of moments that certainly play with the audience’s, uh, expectations:

The Smiling Lieutenant: Making Rank

“When we like someone, we smile. But when we want to do something about it, we wink.”

My wife is a nice, wonderful woman. She is insanely cheerful, with an upbeat attitude that often throws people off. I’ve seen my wife legitimately angry in possibly three, maybe four times in the five years we’ve been together.

I mention this because my wife was livid after the end of The Smiling Lieutenant. From the woman who fawned over Trouble in Paradise and One Hour with You, she could hardly contain her anger at the film’s story. What was it that so enraged her? Let me explain the plot first and then we’ll hit that.

Tooting his own horn.

Niki is a lieutenant in the Austrian army. He’s played by Maurice Chevalier, so it’s a lot of winking, singing, and suggestive ‘ooh la las’. Niki’s army is a standing army, insomuch as there’s no war so they stand around and do nothing. When he’s not in formation, though, Niki prefers spending his time on his back. He’s a sexual hummingbird until he meets Franzi, a violinist in a beer hall orchestra called “The Viennese Swallows.” (Insert your own 1930s oral sex joke here.)

They make wonderful music together, but tragedy strikes one day when Niki is winking at Franzi– because between them is Anna, the princess of the made-up kingdom of Flausenthurm. Flausenthurm is a place like the Freedonia, Klopstokia or The Duchy of Grand Fenwick, where you can tell that something about the country has turned its citizens a few degrees away from normal. For Flausenthurm it’s the size that matters; King Adolf (George Barbier) complains that Austria and Flausentherm were once the same size, it’s only been in the last 700 years that Austria outpaced them. To further complicate their inferiority complex, the King of Austria sent his regrets to his cousin King Adolf that he cannot meet them at the train station for their arrival in Vienna. He will be too busy opening a cattle show.

Anna is a direct corollary of these Flausentherm frustrations. We never see nor hear the story of her mother, but she’s apparently been doted on by King Adolf and a court filled with well-meaning but old-fashioned ladies. Anna’s problem is that she’s like Flausentherm, stuck 700 years ago sexually and socially. When Anna sees Niki’s wink, she takes offense until he explains to her what a wink means. Upon meeting a man of the world– or at least a man who knows what winking means– Anna’s smitten. Niki is modernity, something Anna can barely understand, but is eager to embrace. And, you know, go even a bit further than that.

The response to a waylaid wink.

Niki becomes trapped in a Catch-22, or, to use a more modern parlance, a Kobayashi Maru scenario. If he doesn’t marry Anna, he’ll disgrace Austria and go to prison. If he does marry her, it’s to a wife and country to whom the Magna Carta may be a little too hip and edgy for their tastes. Since turning her down means less than pleasant consequences, he acquiesces to a marriage, but not the wedding bed. In secret, Niki continues his tryst with Franzi while Anna remains puzzled as how to keep her attractive husband home at night. How do you resolve this three way?

Spoilers.

After Anna discovers that Niki is ‘stepping out’ (and shortly thereafter learns what ‘stepping out’ means), she pulls some strings and tricks Franzi into coming to her bedroom. She confronts her, but both find that the situation has made them both a bit delicate. After a couple of slaps and a good cry, Franzi realizes that she can’t keep denying the reality that Niki is really no longer hers. She teaches Anna the secret to modernity via the film’s most catchy– and eye catching– musical number:

And I love Hopkins’ performance in that song. She goes from worry to doubt to wonder to finally finding her own voice in the course of a few refrains. The musical arrangement is great stuff, putting her on the higher end of the keyboard which allows her interjections to Colbert’s jazzy delight to seem fragile but determined. It’s a virtuoso performance in less than a minute!

Anna then does some crazy dancing– and, man, does it look crazy, like she’s shaking out a few centuries worth of cobwebs out of her hair– before she tosses her old ‘cloister bell’ underwear on the fire. Welcome to 1931, Anna.

Ta da.

Franzi departs, and Anna sets to work on seducing her husband. She lures him to her room with some jazzy piano, and then takes a minute to model some lingerie for him. Niki, who took a drink after seeing Franzi’s goodbye letter, runs upstairs and takes a few more sips; truly this transformation is too good to be true.

Upon displaying that she can be modern, Anna coyly resists Niki’s newly discovered sexual desire. She breaks out the checkerboard. She attempts to parry, while, of course, he attempts to thrust. He throws the board to the ground, and she follows it. He picks it up again, this time tossing it on the bed. They both smile at each other. And fin.

My wife was furious at the conclusion and let me know as soon as ‘The End’ popped up. She’d obviously sided with Franzi’s emotional attachment over Anna’s marital claims, and thought the movie was, “A pure male fantasy.” Niki trades up from being an unambitious lieutenant to becoming a prince with little or no effort. Now he’s gone from an affair with a sexy woman to a kept man with a sexy wife.

A pure male fantasy? Why I never.

While I won’t lie and say that that scenario isn’t appealing (unless my wife actually reads this, in which case I’m disgusted that anyone would ever feel that way), I can see what she’s saying. The “Jazz Up Your Lingerie” song can be read that if you want a man, you have to debase yourself to his level to get him.

But I think that it can also be read as Anna finally learning how to express herself. “That’s me!” she declares when she finally gives Niki a passionate kiss in the film’s final few minutes. She wants sex, pure and simple, and until Franzi gets her up to date, she’s stuck in a medieval mindset, which isn’t fun for anyone.

Weirdly, if Anna is the movie’s Eliza Doolittle, that makes Franzi her Henry Higgins. Franzi’s story is what removes this from ‘pure male fantasy’ for me. It’s obvious she and Niki are deeply in love and simply find themselves in an impossible situation by their own making. Both Niki and Franzi have problems with impulse control– the film’s opening joke is about how Niki never thinks ahead. He’s a child of pleasure, and finds in Franzi a similar soul.

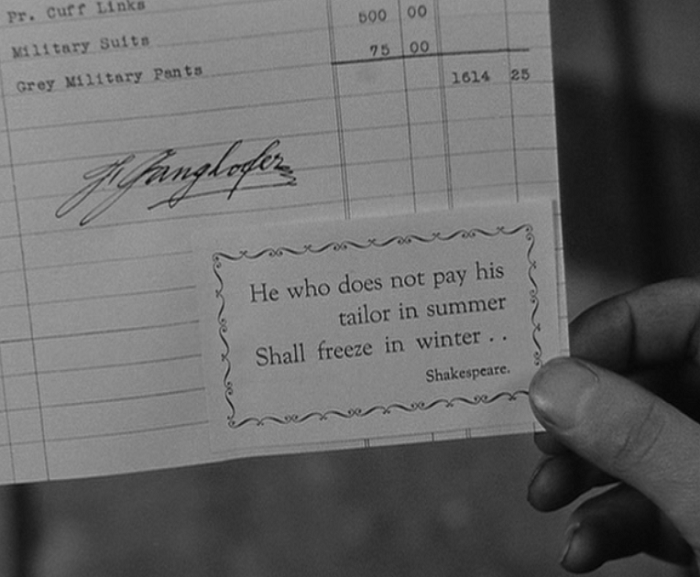

Everything you needed to know about Niki.

But Franzi also understands the real world better than Niki’s flights of fancy– watch as she sneaks out of his apartment once she knows that he’s trapped into a marriage. She can’t help herself when she sneaks into Flausenthrum to watch his wedding, but on a gut level she knows that she’s become the interloper in the relationship because she came back. Once she’s met Anna, it’s confirmed; she doesn’t have the guts to do this to someone so innocent.

Niki doesn’t take the end of either of his affairs with Franzi with much joy. He’d obviously made designs with her that he’d never made with any of his dalliances before. The way Franzi’s final goodbye note ends, pointing out that his wife is blonde and quite attractive (neither of which Niki had even acknowledged to that point) is Franzi telling him that she’s passing the baton. If anything, Niki’s life is taken out of his hands and exchanged by two women who, luckily, are both quite fond of him.

Anna’s blossoming is in Niki’s best interest, so Franzi teaches her to be forthright with what she wants. Franzi heads off into the darkened corridor. Is it unfair that she ends up alone? Yes, but if you think about it, it’s probably for the best that she has the opportunity to find someone better than Niki, no matter how great their breakfasts together are.

The real Anna.

End spoilers.

As per the usual Lubitsch pre-Code formula, there’s a ton of contextual metaphors about sex sprinkled throughout the movie. Playing music together (Franzi plays the violin while Niki and Anna both partake in the piano), checkers, and warfare are all invoked as metaphors for sexual foreplay and compatibility. Even their names (Franzi/Niki/Anna) points towards similarities and contrasts in their chemistry. Everything, every interaction between the characters in The Smiling Lieutenant whether verbal or non-verbal is about sex. Wouldn’t you say that it’s the same way in real life?

A rundown of the actors before I wrap this up. Maurice Chevalier, who has a begrudging admiration from the film firmament as far as I can tell, is just fine in this movie as a Lothario who can’t think with anything besides his large ceremonial sword. Colbert is fine, too, being able to show Franzi as sly and pensive, independent but devoted. She had a lot better work coming, but she nails the ingenue bit perfectly.

But the real breakout part of the picture has to be Miriam Hopkins. This is her first film with Ernst Lubitsch (the other two being Trouble in Paradise and Design for Living), and it’s not surprising that it lead to great things. She has a wonderful ability to portray vulnerability but also overwhelming carnal desire. Her facial reactions are also second to none– if you take anything away from the movie, Hopkins’ delectable, alien-esque wink may just be it.

A lot of reviews I’ve read about The Smiling Lieutenant have broken out the word ‘frothy’, one of those adjectives that doesn’t take a lot of thought to use and really doesn’t make much sense in this context. Like One Hour with You, Director Ernst Lubitsch hides a surprising amount of depth into a romantic comedy boilerplate. A lampoon of Central European pomposity, sexual mores, and, of course, a nice little essay on what it can take to make a marriage work, there’s nothing insubstantial behind the lieutenant’s smile.

… but, if my wife asks, tell her I hated it.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- Not to be a complete dick, but as someone who played the violin for a number of years, uh, yeah, Colbert clearly isn’t playing it. It didn’t take me out of the movie or anything, just something funny I noticed.

- The essay in the Eclipse set (which can also be found here on Criterion.com) has some pretty valuable info, with this interesting nugget:

The infectiously giddy The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) was surprisingly created during a time of extreme emotional duress for its director and star. Ernst Lubitsch was in the middle of divorce proceedings with his wife, Leni, who had been carrying on an affair with his friend and former screenwriter Hanns Kraly. Meanwhile, Maurice Chevalier’s mother had recently died, and the actor was increasingly finding his trademark performance style to be mechanical and insufferable. Already a solemn on-set presence (he was renowned for snapping into his bright-eyed on-screen character when “action” was called), Chevalier was growing more withdrawn, and his working relationship with Lubitsch would continue to deteriorate through mid-decade.

- Plenty of stills and posters over at Dr. Macro.

I wish there was more Charlie Ruggles in this movie. But I feel that way about every movie.

- Criterion Cast explains:

Besides this small scene, a word of advice for Lubitsch newbies: always look for the beds! They function almost like sacred shrines in his films, with every pillow, ornate filigree around the frame and the positioning of bodies anywhere in their vicinity carrying loads of significance that just become funnier with each viewing. The preparation of the “royal bedchamber” in The Smiling Lieutenant is one such scene, that kind of sneaks up on the viewer who doesn’t quite get what all the fuss is about. Simply watch it, think about it a little; the laughs will come full and easy.

- Classic Film Boy notes:

What I really admire about The Smiling Lieutenant is how well it’s held up with the passage of time. I find many early sound films to be static — either they lack movement or are too talky. Lubitsch moves us through the story with ease, and it feels light and fun. It’s also of note that the three stars filmed a French language version of this film. In the early years of sound before dubbing or subtitles took place, the studios would make foreign-language versions of their films.

- Criterion Confessions writes:

The “Jazz Up Your Lingerie” sequence is essentially a vote of confidence for the liberated female and oddly affirms Niki’s love of strong women who can be sexual without being submissive. It’s the free-living lady that Niki wants to take home, and so when Franzi teaches Anna to be more like her, it’s new feminism winning out over old-fashioned morality. The anachronistic setting suddenly makes sense: the Victorian Age must give way to the Jazz Age.

The Lubitsch touch.

- Mythical Monkey, in their appraisal of Miriam Hopkins, notes:

By the way, those looking for an example of the “Lubitsch touch” need look no further than The Smiling Lieutenant. On the royal couple’s wedding night, a manservant and maid prepare the bedchamber—the man puts two pillows on the bed, the maid studies the arrangement, then moves the two pillows together so they’re touching; the man looks it over, thinks a moment, then plops one pillow on top of the other. The man and woman look at each other, smile knowingly, then declare the royal bed ready.

All quite clean yet oh so dirty and served up without one extra word, glance or gesture. That’s the Lubitsch touch.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is available in the Eclipse box set of Lubitsch Musicals. Also included is Monte Carlo, The Love Parade, and One Hour With You. It’s for sale over at Amazon.

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Comments

justjack · August 20, 2014 at 12:26 am

A year ago, Chevalier was for me the butt of a Marx Brothers joke. Since then, thanks to TCM, I have become a great fan. I love his lascivious leer, eyebrow arching, and fourth-wall breaking. Movies like this one can really help to explain to the uninitiated what Pre-Code is all about. And what’s fun about this particular one is how the two women collaborate to structure Niki’s world–the supposed ladykiller is a puppet in their hands. I also concur with your note about Lubitsch’s wonderfully active direction. Now that I’ve seen lots of good Pre-Code movies, I understand that early sound films didn’t HAVE to have a static camera and a microphone hidden in the flowerpot. Good directors could figure it out.

Danny · August 20, 2014 at 11:41 am

Definitely. Even a few real good directors had some problems with camera movement at the beginning of the talkies, but they figured out how to work around it, either in the editing booth or smarter placement.

I’ve always liked Chevalier, but I can understand why some people find his cocky, playful persona off putting. But I don’t really want to be friends with any of them. 🙂

Brittaney · August 22, 2014 at 5:49 am

I was on the fence about whether or not to I was interested enough to watch this, but thanks to your review I’m going to give it a go.

Danny · August 27, 2014 at 3:08 pm

I hope you liked it! If not, I didn’t like it either!

nitrateglow · February 7, 2016 at 1:40 am

I thought this movie was just delightful and agree with you on it not being a male fantasy (at least not 100%). Really, the movie focuses more on how Franzi and Anna are affected by their relationships with Nikki, how Anna is allowed to break free of Victorian morality and embrace her sexuality. Great review!

Danny · February 16, 2016 at 8:31 pm

Thank you!

3D · April 30, 2021 at 7:41 am

What exactly is wrong with male fantasy?

Comments are closed.