The Particulars of the Picture

The Particulars of the Picture

|

|

|

| Kent … Robert Montgomery |

Morgan … Chester Morris |

Butch … Wallace Beery |

The Big House: Breaking Out

Human cruelty, as deep a field as it is, has almost never been better exemplified than in America’s prison system. Barbaric conditions are the norm, as men are made to work as essentially slave labor. Beatings and degradation are commonplace, and an epidemic of rape is treated as a casual joke in the outside world. Recidivism is at record numbers as states continue to incarcerate largely black populations, with some– like Iowa– even bragging about it.

1 out of every 13 men in Georgia is either currently in or has been in prison. Private prisons bilk the government out of money by under training staff and drugging inmates into catatonic states. There’s even a movement to charge prisoners rent for their stays, and re-incarcerate them if they fail to pay. On top of that, America is the only country in the world that freely executes both the mentally handicapped and minors.

There is nothing as brutal in any of this in The Big House, though the film’s view of casual cruelty speaks to the seeds of this national disgrace. The film is a dissection of the prison system of 1930, with the film’s writer Frances Marin having spent months researching the problem.

It’s also definitely not as romantic as we would get in something like Ladies They Talk About, though the movies obviously have different audiences. No cockatoos used as punishment here.

Welcome to hell.

We open up as a paddywagon drives up to the fortified prison’s entrance. Kent (Montgomery) has been put away for ten years after a drunk driving incident nets him a manslaughter conviction. His degradation begins almost immediately; he’s now a number, not a name. He’s undressed, measured, and forced into the same uniform as everyone else, a disturbing paradigm shift for a young man who was used to the lap of luxury.

The warden (Lewis Stone) bemoans that he has to put Kent in a cell with two of the most notorious criminals in the jail: Butch (Beery) and Morgan (Morris). Morgan has been in for a few years on a fraud rap, but it’s Butch that Kent has to be wary of. He murdered three people for $500 and even poisoned the woman he loved. He regrets that last one. Sometimes.

Butch is a brute, someone who’s childlike propensity to flare up and act out has never been fully subdued. Sweet as a kitten one minute, shoving a knife in your gut the next: not an ideal roommate. Morgan has got a handle on this routine though, and manages to keep Butch’s lid on whenever possible.

“Get this, Butch– apparently you’re allergic to dirt! No wonder you’re always so irritable.”

Morgan, of course, has problems of his own. After Butch slugs Kent and knocks him out cold after Kent rightfully accuses him of stealing his cigarettes, Morgan demands Butch put the kid in his bunk and give the cigarettes back. Butch, who shies away from this deed as soon as he’s confronted, grudgingly complies. Morgan picks up the cigarettes himself and lights one up; he may have a more refined sense of morality, but scruples never seem to have been his strong point.

After Kent is knocked cold, the movie switches gears a bit, which is the first instance of how masterfully constructed The Big House is. Rather than let the audience become too comfortable with Kent as the meek man in the scary world, our sympathies and story begin to follow Butch and Morgan. The movie always manages to quietly stick to what by now is an established formula while playing with the presentation enough that it still feels fresh.

While Butch is belligerent (and has a knife, to everyone’s dismay) and Morgan is playful but selfish, Kent begins to consort with the prison stoolies. In most other movies this would be a heroic thing, trying to get the guards to take down Butch’s own gang who regularly gamble and plot escape attempts. However here the prison officials range from cruel to power hungry themselves. Their desire to put Butch in the dungeon– a deep underground cell where he will be in solitary for a month all alone– seems to stem from an unacknowledged inferiority complex. Their power comes from beating down the prisoners, and they love their jobs.

I’m going to guess that this place is even less fun than it looks.

The jail itself is built for 1800, holding 3000. The warden bemoans this (again, among other things) and speaks as the unsubtle audience’s conscience for the first half of the picture; this changes later on. But from the start, he sets himself up as an unwilling angel who doesn’t get the money to treat the prisoners with the respect or facilities they need. With this situation set up and Butch stirring up trouble, a confrontation is certain.

Kent obviously isn’t ready to deal with any of this; in fact, his drunk driving charge would seem to indicate that he’s barely ready to handle adulthood. He cracks easily, and attempts to make no friends in prison with anyone he judges as criminal or callous. He especially dislikes Morgan, most notably after Morgan began talking about just how cute Kent’s sister is.

Even their lunch activities follow a formalized process, with whistle blows indicating when they’re allowed to sit down, flip over the bowls, and welcome the food. The confrontation I mentioned before comes to an early head as Butch snaps at the guards during one particularly awful serving of slop for lunch. He raises up a yell at the guards and soon the prisoners are throwing their utensils and plates in a broad melee. The guards take aim with their guns and ask butch if this riot is really that good of an idea.

He finally stands down. While Butch is impudent to an extreme, he’s also wily enough to know when to pick his battles. That’s what makes him so dangerous.

Marching to the beat of a silent drummer.

Butch is placed in the dungeon, but not before the knife he was carrying gets passed down the line until it ends up with Kent. A surprise bunk inspection is later called to try and track down the knife, and Kent, upset at Morgan for his bossiness and comments about his sister, plants the knife with his stuff. Morgan, who had just discovered that he was to be released the next day, is none too pleased when the guards find it and decide to put him in the dungeon as well. Kent’s now safe from the two biggest thugs who’ve made his life miserable, but he also knows Morgan will be gunning for him in 30 days.

But Morgan’s first thought when he’s pulled out of the dungeon is a different kind of revenge. Feigning exhaustion, he’s placed in the hospital where he cleverly switches places with a dead body. His plan works, and soon he’s on the streets– a wanted man, but free.

After Morgan’s escape into the foggy city (I presume it’s San Francisco, but don’t quote me on that), he meets Kent’s sister, Anne (Leila Hyams), like he planned. The movie rightfully leaves the question in the air: is he there for revenge on her for what Kent has done, or is there something softer inside him?

She covers for him when a cop arrives, and their romance blooms. He loses his edge quickly, and, after his recapture, is even forgiving and paternal towards Kent. Unfortunately, why he was out on the lam, things have grown more complicated at the prison.

Anne seems curious about all of this too.

Bringing Down the House

This next section has spoilers; skip ahead to the next header if you want your eyes to remain pure!

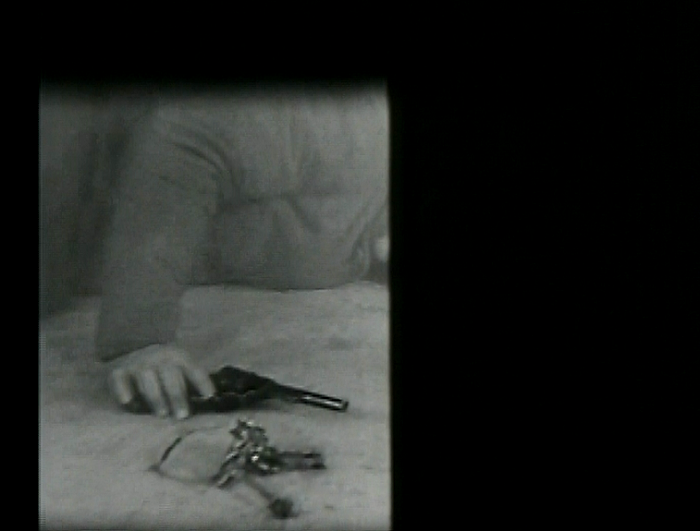

Butch has finally put together a solid plan for escaping the prison, and Kent has gone completely yellow and told the warden everything that he knows. That means that the warden knows when, where, and how the escape attempt will be made. What he doesn’t know is how they’ll get the guns.

The warden uses this as an excuse to put off taking down Butch’s gang, fatefully waiting until the exact time the attempt is planned before making anything but cursory moves.

Some have pointed this out as a flaw– the warden knows when the attempt will take place, why leave so much leeway for Butch to make his move?– but the answer is simple: for all of his moaning about the state of the prison, he is still in charge and must once more prove his dominance.

He’s given Butch’s gang enough leeway to attempt an escape, but not enough to actually succeed. The implication here is that maybe the warden is using this as an excuse to trim down that prison population that the outside world doesn’t care so much about. This seems to be reemerge time and again in reports of real life prison abuses.

Everybody run, Beery’s got a gun…

As for the final breakout attempt by Butch, which involves him mistakenly believing that Morgan was the one who snitched on him, is as exciting as any action sequence from the 1930’s that you’ll get. Without Morgan’s conscience, Butch has let his baser instincts go, killing guards and becoming aggressively bloodthirsty.

Kent, who gets trapped in the prison with the rioters, begins a final, fatal meltdown. After seeing the violence he’s wrought, he squirms away from Morgan– whose paternal instinct has drowned out the knowledge that Kent has essentially set him up to be killed by Butch– and runs into a hail of machine gun fire. If he’d kept his mouth shut or trusted Morgan, he’d have made it out alive… but more on that below.

Morgan does a couple of daring things, and locks up the prison guards to save them from further execution by Butch. He runs off with the keys and a machine gun toting Butch chases him. They have a classic stand off which ends with the two rekindling their friendship on one level, and both coming to a brief, sad, understanding before Butch’s injuries finally release him from his troubled life.

For his deeds, Morgan is freed with a full pardon, and while he returns to Anne, it’s doubtful as to how much he’ll tell her about his experience on the inside, or just how big of a worm her brother really was. Personally, I think he’ll spare her the gory details: he understands why Kent did what he did. The lie is worth the pain.

See, happy ending! Everything is okay! No sadness ever!

On Acting and Not

Director George W. Hill famously told his cast at the beginning of making The Big House, that he’d fire the first person he saw acting. This may seem like a silly admonition today, but coming directly from the expressive faces of the silent era, a fear of hammy performances in something that could easily have become a routine melodrama makes it a thoughtful threat.

He may have mostly been directing this at Wallace Beery. Beery, a long running silent actor who’d found himself badly out of work with the arrival of the talkies, does some excellent work here. He manages to vary innocence, camaraderie, and violence into a charming package that many future crime films would cash in on. He’s never easy to pin in the film, which is another element that makes it continue to seem fresh.

Also of note is Chester Morris as Morgan. Morris excelled as those men who skirted the line between dashing and scummy. Well known for both The Divorcee, Blondie Johnson, and Red Headed Woman, here he achieves a delicate balance as a fraud and a cheat whose better nature and bad nature are at constant odds with each other. This may be the best I’ve seen of him so far, and his chemistry with Beery is nothing short of sensational.

That Stone Cold Look

I just wanted to make a few brief notes about Hill’s direction and his compositions in a few scenes, with some pictures to illustrate:

Here’s Morgan being led to the dungeon. Most of the scenes set in the prison are either cramped tight or wide open, with guards looming over the proceedings.

After he’s escaped and is planning on leaving the states, Morgan’s walk to Anne’s house stands in stark contrast to his prison life. However, here he’s unknowingly being closed in on by the police. Looks strangely foreboding, right? Compare this to the picture above.

This is from when Kent enters the prison. It’s coldly casual as he’s stripped and every inch is measured. The man in the foreground is a little too close, and it feels like we’re peering right over his shoulder.

Here’s the chaos of the final showdown in the prison. The camera moves quite a bit, and foregrounds objects to give the audience a more ready sense of involvement.

In a couple of shots, Hill uses foreground objects brilliantly. The camera is under an awning here, putting this final scene of the prisoners’ orderly march a feeling of grandeur and foreboding. It also temporarily makes the film widescreen, which is pretty cool.

Another ‘objects in the foreground shot’, where the door outlines the gun that Morgan needs to rout the prison riot. This comes from a silent tradition, but still works wonders here.

While the riot goes down, Hill takes pains to separate Morgan and Kent into their own one-shots as Morgan slowly realizes that Kent’s been setting him up most of the time.

Yeah, that’d be my reaction too.

The Hero and the Dead

What is the purpose of prison? Is it to punish or reeducate? This is the dilemma that our country has always found itself in as it’s always wrestled between an eye for an eye and turning the other cheek.

I bring this up because this conflict is central to what makes The Big House still feel so contemporary. You can see what the prison wants to do, and what it succeeds in doing. Whether this is in spite of itself or as a miniaturize of the outside society is up for debate.

If the purpose were truly reeducation, Kent wouldn’t have met the end he did. Everything the prison tries to do, from stripping people of their names and identities, is to foster a sense of teaching conformity. As my friends, the former Japanese school teachers, are so fond of saying, ‘the peg that sticks out gets hit with the hammer’.

If we hadn’t had this riot, what excuse would we have had to gun down all these prisoners?

Unfortunately, this systemic attempt is undermined in several places, by the power hungry and vicious guards to the bitter and violent inmates. The attempts to teach solidarity simply lead to greater and greater power plays, with each side having to flex its muscle in a macho attempt to one-up each other.

The movie subtly depicts this competition, from everyone’s failure to actually call the inmates by their assigned numbers to the brutal snitching system which perpetuates itself: guards encourage bad behavior so they may punish it to deter bad behavior which creates resentment which encourages bad behavior which the guards further encourage… etc.

This fundamentally undermines the prison’s clinical approach, and it seems no one has been able to figure out how to readjust the equilibrium. Affection and faith are what makes Morgan a hero in the end, and, quite notably, neither of these attributes he gained in prison. No one, not even the warden, seems to notice this. The only thing anyone gets out of the big house itself is a lesson in brutal, cyclical violence.

The Big House remains one of the best illustrations of how to make a message picture right. Thanks to some great acting and a smart script, the film remains fresh and troubling to this day.

And god help us all.

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Butch the illiterate pretends like the letters he receives from the outside are quite naughty. “The rest of this is too juicy for you guys!”

- One poor inmate lugs around magazines for the others to borrow and read. We learn that one, called “Bride’s Confession”, has been ‘worn out’.

- One of the rare uses of a four letter word here, with the Warden responding to Butch’s demands with a fiery, “I’ll see him in hell first!”

- And, as noted above, a lot of people die horrible violent deaths, from gunshots to poisoning.

Gallery

Here are some extra screenshots I took. Click on any picture to enlarge!

Trivia & Links

- The most interesting bit of trivia I found (via the indispensable Movie Diva) was that the film was heavily reshot after a test screening. Originally Kent’s sister was supposed to be his wife, and a bad test audience reaction resulted in some reshoots and clever editing. I can see why this first version was rejected, since it makes Morgan more of a heel and would make the ending a little more cut and dry.

- The film’s writer, Frances Marion, is the first woman to win a non-acting Oscar. She based the film on a series of interviews and prison visits she did, and would later go on to write a host of Beery’s future films, like The Champ and Dinner at 8.

- Where Movie Diva touches on where the movie came from, A Wasted Life touches on what happened to its principals next. It even makes a sly note that Robert Montgomery playing a snitch here is appropriate as he would testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee two decades later.

This may be the best Chester Morris has ever looked, btw.

- Mythical Monkey talks about Wallace Beery’s role and career, and looks at a few of the themes in the film that make it so potent. A lot of people seemed to be really bowled over by Beery in this movie, and I think he does some really solid stuff here.

- Prison Movies admits the movie kind of lost them in the last 20 minutes, but says it stills holds up pretty well.

- Judging from the Turner Broadcasting logo and the box art, I just wanted to warn you that The Big House is one of Warner Archive’s earlier releases, and thus doesn’t look very pristine. A similar thing afflicted Private Lives (hey, which also starred Robert Montgomery); a remastering would be nice, but the film isn’t indecipherable.

“Best friends forever, Morgan?” “Forever and ever, Butch.”

- Another brief aside: both Montgomery and Morris also starred with Norma Shearer in The Divorcee the same year this came out. I think Morris is a lot looser and more fun here, but I think the material helped with that.

Awards & Accolades

Availability

- This film is available on Amazon and Warner Archive, and can be rented from Classicflix.

|

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar!Home | All of Our Reviews | What is Pre-Code? |

7 Comments

Grand Old Movies · April 19, 2013 at 4:25 pm

Thanks for posting on this film and for your discussion on our benighted prison system and how this film reflects (still) on that crisis. I saw this movie many years ago and the memory of Wallace Beery’s performance is still vivid in my mind (his way of switching on the instant between smiles and rage is terrifying). Chester Morris had a talent for playing morally ambiguous characters, which he did so well in pre-Code films (and if you want to see a really mean Morris, I mean REALLY mean, see his performance in the 1936 Three Godfathers). I love prison break-out movies and this is one of the best.

Danny · April 19, 2013 at 6:29 pm

I’ll definitely add Three Godfathers to my watchlist, Morris can be surprisingly great when he wants to be. Thanks for your comment, I appreciate it!

Dino · January 5, 2016 at 2:40 pm

Thanks for this review. Just bought the DVD which has two foreign language versions (French and Spanish) shot simultaneously.

Danny · January 8, 2016 at 1:08 am

Yeah, that just came out recently. I hope they remastered the English language version for you while they were at it. 🙂

Dino · January 8, 2016 at 11:11 pm

Just watched it last night. Can’t tell if it’s remastered (probably not) but it looked okay to me. Great site, by the way!

Danny · February 16, 2016 at 12:32 pm

Thank you! And I know the old Warner Archive DVD still had the old “Turner” logo on the front of it, which means it was a VHS remaster they put on DVD. I’d be surprised if it was an upgrade, but would still be happy if it were.

Brian Paige · December 24, 2019 at 7:15 am

Just watched this again last night. The thing that baffles me whenever I see this film: Why didn’t Chester Morris become a megastar? Beery used this film to skyrocket up the box office star charts and get an Oscar nomination. Montgomery was clearly considered inferior to Morris at this point, yet he hung around MGM forever and was a solid A list star. Stone was a character actor at MGM for years. Morris was a real standout in this film and it baffles me that he just veered into B movies and Boston Blackie. I think it might be that it was tough to cast him in ideal roles. His whole “tough enough to be a tough guy, but good looking enough to get the girl” vibe was tough to really hone in. It’s a shame he never played Dick Tracy. That would have been the role for him.

Comments are closed.