Private Life of Henry VIII: A Royal Rumpus

“You smile, do you? Smile while you may. You’ll find the throne of England no smiling matter!”

By complete and utter chance I had PBS on the other night. I know, I’m 33, I’m supposed to be arguing over the internet over the best Pokemon (Bulbasaur) or going to eateries that serve 12 different ‘microbrews’ that all attempt to taste like Reese’s Peanut Butter cups (did that the night before). No, I was watching PBS because, as a person who believes in being an adult, I wanted to watch something that would expand my mind and, hey, Lucy Worsley is easy on the eyes.

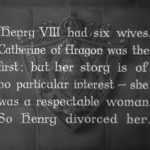

That documentary shared much in common with 1933’s Private Life of Henry VIII, mostly involving the very British winks and nods at Henry’s sex life, a subject that reshaped their entire nation thanks to its role in fostering the English Reformation. (This is humorously skipped over in the film with a title card, a nod to the fact that it wasn’t the end of his marriage to Catherine that fascinates, but his serial inability to be satiated.) A fatuous man, Henry could be a smart leader, but his relationships with women ended precariously.

This movie, which was released in the U.S. unedited as far as I could discover, is a mix between a character-driven tragedy and a bawdy farce, though the emphasis is most decidedly on the latter. And I don’t exaggerate the bawdiness– the ladies in waiting, as we ourselves are waiting for Henry to make his appearance in the movie, chat excitedly and rib one another about Henry’s rumored proclivity, one woman even going so far as to sniff his bed. This happens as Henry’s previous wife Anne Boleyn (Oberon) waits on the gallows, and his new wife, Jane (Barrie), waits in the chapel.

It doesn’t take much more than a foggy recall of history to know that Jane’s reign won’t be long lived, but it’s short and sad– she dies in childbirth after producing his only son. He’s almost content to stay single and remain in mourning, but soon finds himself under social pressure to marry a German princess to prevent a war. The famous fornicator bemoans:

“Am I the king or a breeding bull?!”

Considering his well-known rumpuses around the court and with the help, one once a more gets the idea that Henry simply doesn’t want to do something because he knows he should. He’s a child brought to rear throughout the film, Laughton licking his chops as he gloriously dives in to the id embodied.

The film’s highlight is the Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves (Lanchester), a marriage made for political gain that sours quickly thanks to a good effort from all involved. Anne sets herself up to look unattractive and dense, and then she further pricks at Henry’s ego. A speedy, quiet divorce is made, and the ambitious Katherine (Barnes) lands Henry next. But Katherine also loves Henry’s highest advisor, Culpeper (Donat), leading to once-more predictable results.

The film sets up an interesting contrast in Anne and Katherine– both women want power and autonomy, but Anne uses her wits while Katherine recklessly submits her body. Anne knows better than to trust Henry’s temperament and preys on his weaknesses, while Katherine instead succumbs to her own desires despite damn well knowing better.

Henry himself is a boisterous mess of a man, desperate for what he wants and coldly calculating when he needs to be. He’s the type of person who clearly shouldn’t be given an ounce of power, but instead finds himself able to wield his hand freely, which often leaves him kicking his own rear end.

There’s a lot of praise to given to the cast. Merle Oberon, who is only in the first few minutes of the film, gives a haunting performance as the doomed Anne Boleyn, which was enough to eventually help boost her to becoming a star. Elsa Lanchester cleverly plays Anne of Cleves as chess player while also wringing out laughs from cleverness and offbeat deliveries– shades of her future as the Bride of Frankenstein appear here. And Charles Laughton, who won the Best Actor for his role here, chews the scenery with aplomb, something the actor did often. However, he does find some measure of nuance in Henry, giving the sex-hungry king a layer of tragedy as his bad (and often horny) decisions destroy his own chances of happiness over and over again.

But the real star has to be Korda’s eye and the film’s superb look and design. The film’s opening is gripping, as the death of Anne and the wedding to Katherine are intercut, with dramatic ironies piling upon one another. Laughton’s entrance is equally stunning, a blustering recreation of one of Henry’s most famous portraits, instantly identifying him and drawing him from the history books. The film isn’t studio bound (thanks to budgetary reasons rather than practical ones) which gives it a lot more of a jolt than other pictures of the time. Korda’s need for creativity gives the film a fresh, zesty life.

The Private Life of Henry VIII is a naughty farce that focuses on the bedroom and provides plenty of guffaws. As it’s from England, it’s not technically what I’d call a pre-Code, but I’m covering it because it’s one of those films that flow along in the zeitgeist of the era. Here is power deconstructed, ridiculed, and yet understood with sympathy, even if it doesn’t deserve it.

Gallery

Click to enlarge. All of my images are taken by me– please feel free to reuse with credit!

Trivia & Links

- Cliff at Immortal Ephemera heaps praise on Laughton’s work here:

But nothing colors Korda’s picture more than Laughton’s Henry. From his first moment on screen, hands astride hips with his booming voice interrupting the gossiping ladies of his court, there is no doubt about who’s in charge. If this man weren’t King surely some other would have had his head on the chopping block long before it swelled bigger than his bulging body. His pompous amble demands attention as does his explosive laughter and equally combustible temper.

- TCMDB talks about how this film springboarded Hungarian director Alexander Korda to the ranks of great film producers:

The Private Life of Henry VIII was the first British film to become a hit in the United States, and in addition to Laughton’s Best Actor Oscar®, the film was nominated for Best Picture. It was Korda’s dream come true, a film that captured both popular success and critical respect, and it made his fortune. Korda continued to direct, reteaming with Laughton on Rembrandt (1936) and directing Laurence Olivier and Vivian Leigh in That Hamilton Woman (1941), among others. But most of his energy went into expanding his company and producing increasingly lavish and ambitious films as The Four Feathers (1939), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), The Jungle Book (1942) and The Third Man (1949).

- The New York Times called this, “a really brilliant if suggestive comedy.” Mordaunt Hall continues:

It is a remarkably well-produced film, both in the matter of direction and in the settings and selection of exterior scenes. There are several lovely glimpses of old structures, including the Tower of London. No knives and forks were used in that day and therefore the always scrupulously dressed monarch thinks nothing of devouring a chicken in his hands and tossing the bones to the floor.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is in the public domain. I caught it on Amazon video, and you can get it on DVD part of the Alexander Korda’s Private Lives Eclipse set.

More Pre-Code to Explore

4 Comments

realthog · March 10, 2017 at 7:13 am

Lucy Worsley is easy on the eyes

Maybe so, but I can’t stand her screen persona.

Patricia Nolan-Hall (@CaftanWoman) · March 10, 2017 at 8:10 pm

Every time this movie enters my orbit I am reminded of how entertaining it all is. Laughton really deserved that trophy.

Elizabeth · March 12, 2017 at 4:16 am

Because his entire acting persona supported it. We need more pretentious professors with books analyzing Charles Laughton.

Lucius Vanini · February 25, 2018 at 6:18 pm

A PRODIGIOUS film, a lifelong favorite of mine, and it shows the great Laughton at his best, an easy winner of Oscar for Best Actor of 1933.

Comments are closed.