We take color for granted nowadays. That was my main takeaway of The Dawn of Technicolor, a look a the growing pains of the Technicolor company as they begin the drive to put color into motion pictures. The ability to get feasible, realistic color to be produced consistently and delivered quickly was crafted by some of the smartest men and women in the country who refined and rebuilt their methods over a decade and a half of hard work.

Beginning with the company’s formation in 1915, the book takes the reader step by step through the logistical problems the company encountered. Technicolor was founded on the belief that color in motion pictures was an inevitability, and that an independent business that overcame all of the daunting challenges to create a proprietary system would clean up in the market. The company’s founders were sourced from MIT and other Ivy League universities. Technicolor developed its famous two-strip system by the early 20s and even produced a few films themselves to show of the technology.

Two-strip had its share of problems, such as the inability to create rich blues or the color yellow. Technical problems were also present, as it was important to be able to build color film that could be used on then-widespread mechanical projectors, meaning that all the color information had to be built on a single film strip. Producing and reproducing the film quickly on a large scale also became a problem, and the company saw its fortunes rise and fall several times, almost immeasurably.

Then there was also the matter of filming– early cameras required massive amounts of light to register pictures, and Technicolor cameras required even more, doubly complicated once sound technology came on the scene. The technical aspects didn’t just affect the researchers, but everyone on the sets of the films as well:

The more than 8 million watts blazing down on them helps to explain the tales of intolerable heat on the sets that actors found so oppressive. Normal makeup would melt in streaks on an actor’s face. “I’ve seen actors stand there with their hair smoking,” recalled sound engineer George Groves. “If they had a little grease on their hair, it actually would start to smoke from the heat. It was just terrible– almost impossible to stand.” (pg 220)

There are many other technical issues, and the book includes dozens of original diagrams and photographs showing the development and tribulations faced– once the technical challenges are figured out, it’s the production issues that that become paramount, as well as the need to create three-strip technicolor with all of the improvements that that entailed. But the real fascination for movie buffs is the chance to see so many gorgeous stills of two-strip Technicolor from a stunning variety of sources.

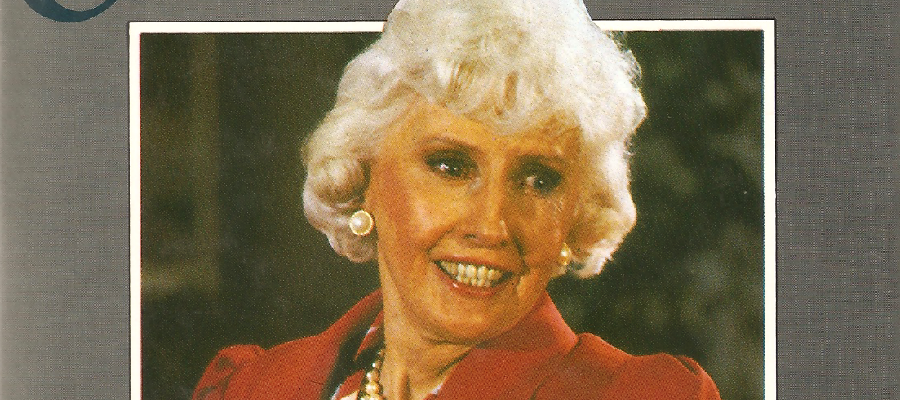

Clara Bow appears in two-strip Technicolor.

In fact, one of the central attraction’s of the book is its exhaustive index of Technicolor films up until the production of the first full-length three-strip Technicolor film, Becky Sharpe, in 1935. As Crystal Kui explained on the Eastman House’s blog:

During our research we identified a significant number of films that were overlooked in other filmographies. Two years ago we started with a list of 141 two-color Technicolor films compiled from various published sources. In its complete form the filmography now accounts for the existence of 371 features and shorts, in addition to fourteen abandoned productions and tests for which color footage was shot but never shown to the public.

It’s this exhaustiveness that makes it so valuable. While there are a number of side stories involved in tracking down defects and figuring out bugs, this one is probably the funniest of the bunch:

Teething problems persisted, however, and the Research Department was always mindful of keeping things in check. One such problem presented itself in March 1927, soon after [ink bath] production was fully implemented. A drop in image definition was noticed, but its source could not be found. After some digging, [Leonard T.] Troland came to the root of the problem. “We have… traced this loss of definition to dilution of the alcohol drying bath on the matrix developing machine, and circumstantial evidence makes it very clear that the solution room man in charge of the alcohol had been bootlegging it and substituting water in its place.” The problem was soon remedied. “Naturally, we are discharging him this week-end, although the evidence in our possession may not be sufficient to convict him before a jury.” (pg 153)

Casual readers may be a put off– while it’s indeed about film making, it’s stripped down and unglamorous. Much of the first third of the book is about technical challenges involved in motion color photography. There are key people who are followed throughout the book such as Herbert T. Kalmus, Natalie Kalmus, Judge Jerome, and dozens of other scientists and investors, but most of their personal stories take a distant backseat to Technicolor’s business dealings. The book lacks a certain amount of personality in that regard, and can be hard to get through unless you are intensely interested in the mechanical side of things.

And some people are! The Dawn of Technicolor is for those movie lovers who want to understand more than just the stars and studios of early Hollywood, but the technical side as well. It’s a handsome book and will be an invaluable reference for decades to come.

Notes

- Reading level: Academic

- Length: 300 pages, 448 with endnotes

- Thanks to the George Eastman House for providing a review copy of this book. You can read more about the process that went into making the book here and here.

This book is available from Amazon.

6 Comments

Vanessa B (@callmeveebee) · March 18, 2015 at 2:55 am

I’m sitting here reading your post and SALIVATING onto my keyboard. I want it, I need it!

Danny · March 19, 2015 at 12:21 am

It’s not a cheap book or an easy read, but it’s fascinating nonetheless. Get it from Amazon! Get it good!

shadowsandsatin · March 18, 2015 at 3:27 am

Hi, Danny — I had no real interest in this book or this topic until I read your review. Now you have presented me with yet another dilemma in my TCMFF planning. Thanks ever so much. ;o)

Danny · March 19, 2015 at 12:23 am

The Dawn of Technicolor showing is definitely one of my musts since the book is so comprehensive and tantalizing. Here’s hoping there’s a compilation or video of the presentation released later, because there’s so much sporadic footage out there that I hope it gets more widely seen and celebrated.

Dulcy · March 18, 2015 at 5:22 pm

Hmm! Anything on two- and three-strip animation (“cartoons”)? Disney and Technicolor had an exclusive deal, but there was color out there before “Snow White”.

Danny · March 19, 2015 at 1:53 am

Disney gets brought up near the end of the book and their deal is discussed starting around page 274. In 1933, Disney is one of the first to get three-strip Technicolor which turns out to make their cartoons highly profitable. It also makes black and white cartoons pretty much obsolete overnight as audiences clamor for color. Because of the exclusivity deal, Technicolor can only let competing studios make two-strip Technicolor cartoons, so there are entries for the toons made by Fleischer and others who are trying to cash in on the new craze. There are more details in the book (obviously), but it’s an interesting story.

Comments are closed.