|

|

|

| Jerry Young Fredric March |

Henry Crocker Cary Grant |

Mike Richards Jack Oakie |

| Released by Paramount | Directed by Stuart Walker Run time: 72 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- There are plenty of awful moments of combat, including a hand covered in blood and plenty of other bullet- riddled corpses.

- “You may be Fifi to the rest of the world, but you’re nothing but ‘Fanny’ to me!”

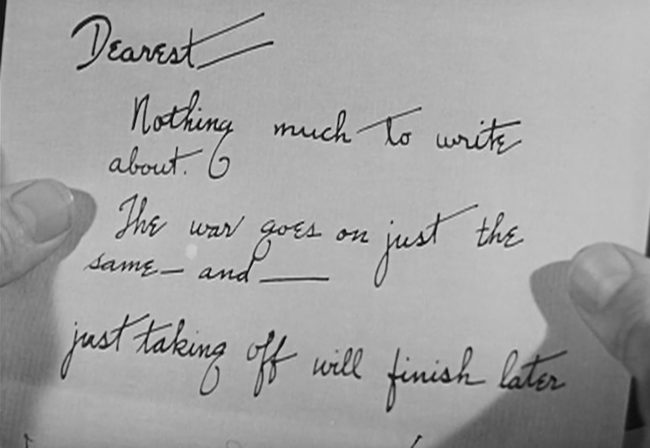

- A vacationing soldier meets a sympathetic woman. He and her head to the park at night, and exchange this before a suggestive fade out:

“You’ve been awfully kind.”

“I want to be kind.”

- The film’s ending is extremely bleak, let me put it that way.

The Eagle and the Hawk: Tailspin

“Someone will get a nice, shiny medal for this.”

Coming in about as acidic as all of the pre-Code World War I dramas could, The Eagle and The Hawk is a deeply cynical film about man’s goals in waging war. It’s to kill each other– we all knew that, right?– but the toll that it takes on the souls of soldiers is always what’s hard to reckon.

Fredric March, who seems to have barely washed his face from his role in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, here plays a bon vivant American that enjoys polo and flying. March’s Jerry Young decides that the World War looks like fun, so he heads to England to train to be a pilot. There he meets cut-up Mike Richards (Oakie) and Henry Crocker (Grant), who has a chip on his shoulder the size of France.

Young and Crocker face off, with Young getting Crocker demoted to being an observer over Crocker’s inability to land planes– a necessity for pilots. Young and Richards head to France where the jubilation of their first confirmed kills are quickly buttressed with Young’s gunner dying — the first of many.

Young’s psyche deteriorates from there. Awards pile up for his bravery just as the corpses do. Crocker makes it to the front and becomes widely despised in his unit — he keeps machine gunning the parachuters. Crocker and Young exchange punches, and while I won’t say a respect develops, they begin to realize they see the war in the same way; it’s a fight for survival. But where Young sees nothing but a spiral of pain and misery that he’s trapped in, Crocker’s upstart ways give him a pride in the bloodshed and havoc he’s wreaking.

There are more medals and more dying. The Eagle and The Hawk, which seems to have much of the same airplane combat footage every other pre-Code war drama was using at the time, traffics in an escalating scale of nightmares on the ground. This includes one stunningly grim sequence where Young, flying in a loop, sends a dead airman falling out of the plane. We’re trapped with him, watching the corpse of the innocent kid wind its way painfully down to the muddy earth below.

March’s eye makeup modulates as his mood descends, and there’s a gnawing intensity to his performance. You can feel him riding the mood of his Oscar nomination, banging around inside the character and pulling every dark thing out. Cary Grant is a little rough around the edges as Crocker– he can’t quite find the right note at being the respectable punk the movie wants; he’s always too likeable. I don’t say wild and crazy things like this often, but Crocker needed to be Pat O’Brien.

Carole Lombard makes a brief appearance as a London socialite who takes March’s character to Hyde Park and let’s him ramble and take a load off. Lombard doesn’t have much to do besides look stunning, and her total screen time is probably less than five minutes. She may as well have sent over a doll to do her part instead.

The Eagle and the Hawk is a film so downbeat and grim I had to laugh by the end– it was either that or spill wet, sobbing tears. If the film has a flaw, it’s that March’s Young never really loses anything besides a sense of naivete, and his points about the grim grind of war are obvious. Mind you, it’s still a shock to hear them stated so plainly– so often we have about a dozen layers of good vs. bad bullshit meant to allay us of these simple truths. But while the film looks great and is undoubtedly shocking in a number of pre-Code ways, it lacks a final, bitter punch– it doesn’t have the emotional completion of similar World War I anger fests Ace of Aces or All Quiet on the Western Front. That may be because of the noble bow tied around the ending that fixes Crocker’s character and leaves a memorial to our hero untarnished makes things too easy, too perfect.

But the film remains a good example of the kind of raw fury that existed after the Great War. By the end, March is screaming at his squadron after his best friend is dead and he’s seen yet another young dopey child die in his gunner seat. His pained rant falls on deaf, pointedly inddifferent ears, and that sudden reveal of the magic trick that America continually plays on itself– that the war isn’t there, that Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, aren’t there if you aren’t looking at them— and March’s primordial scream of emptiness will continue to echo with the same urgency as it ever has.

Screencap Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- TCMDB lavishes praise on this one (I mean, they did release the DVD), and goes into how much off their usual personas Lombard and Grant are. They also talk about its place in early World War I films:

Made in a time when the world was fascinated with aviation, the flight sequences many borrowed from Wings, Lilac Time (1928) and The Dawn Patrol (1930) and utilizing anachronistic planes — are smoothly integrated into the film. (John Monk Saunders got story credit for this film, Wings and The Dawn Patrol). Stuart Walker is listed as director, although Mitchell Leisen, later to be known for romantic comedies, claimed at the time of his reworked version of the 1939 re-release that he had directed much of the original. Either way, it crackles with urgency. […]

Ever more alienated from his hero’s mantle by his unsparing perception of himself as murderer, he’s the film’s soul as it makes its points with a grim, unflinching integrity that compels respect and makes you wonder why The Eagle and the Hawk isn’t better known. It fully deserves a place alongside that foremost WWI antiwar film, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and the seismic values shift that animates Jean Renoir’s great The Grand Illusion (1937).

- In one of my favorite articles of his, Erich at Acidemic talks about the career of John Monk Saunders

What I dig most about EAGLE AND THE HAWK is just how flimsy the WWI bi-planes here seem. They look ready to fall to pieces at a moment’s notice, little more than kites with guns attached. […]

What’s less exciting is the way, just like Kirk Douglas in PATHS OF GLORY (1957), Jerry’s self-righteous anti-war stance includes blissful freedom from the big picture, i.e. the responsibility endured by Neil Hamilton in DAWN PATROL. It’s very convenient to bad cop it to a higher-up and play the wounded dove without worry of the long-ranging sociopolitical consequences. […]

La Salle notes that Jerry’s suicide had a real-life parallel to Saunders’ real life booze-enhanced turmoil: “Seven years after the film was made, Saunders, age 42, hanged himself.” (105) That would be 1940. You do the math; he died along with any socratic ideal of a future negotiated peace with Hitler. He also probably realized, as so many drunks do, that sobriety was his only other option.

- CaryGrant.Net features a number of reviews both past and contemporary. Here’s Mordaunt Hall from the Times:

It is, fortunately, devoid of the stereotyped ideas which have weakened most of such narratives. Here is a drama told with a praiseworthy sense of realism, and the leading role is portrayed very efficiently by Fredric March.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

More Pre-Code to Explore

1 Comment

Terence · April 1, 2018 at 8:20 am

It’s a tough call between this and Ace of Aces. In many ways, Ace of Aces has a better, more pointedly dyspeptic script. But I think March is a better actor than Richard Dix. I’m in that minority of people who like 1939 Dawn Patrol better than the Hawks one (1930) even though it is almost a scene for scene remake right down to the stock footage from the first one largely because Basil Rathbone is so good as the c.o. WWI flying ace movies are probably my favorite subgenre of war films. I marvel at the old flimsy bi-planes. That said, the air war came late in the conflict and its importance was somewhat exaggerated by Hollywood probably because so many writers and directors — Saunders, Wellman, Hughes and Victor Fleming — had been aviators and because Wings (1927) did such great box office. I agree that Lombard and Grant are largely wasted in this one though Lombard, as always, was lovely to look at.

Comments are closed.