|

|

|

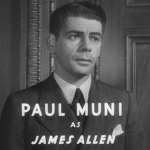

| Jim Allen Paul Muni |

Bomber Wells Edward Ellis |

Marie Glenda Farrell |

|

|

|

| Helen Helen Vinson |

Rev. Allen Hale Hamilton |

Barney Sykes Allen Jenkins |

| Released by Warner Brothers | Directed By Mervyn LeRoy |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- A Texan assures us that the next man who asks him for an inspection will be “S.O.L.”

- An innocent man is convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. He’s placed on a chain gang and works under dehumanizing conditions that regularly includes men being whipped, beaten and denigrated in a variety of gruesome ways.

- Having escaped the chain gang, our protagonist, Jim Allen (Muni), hides out in a friend’s boarding house where there’s liquor and a woman named Helen who will keep him company.

- Jim lives with a woman before they’re married, and they get married because she blackmails him into it. And then she runs around with other men, just to put a cherry on top.

- “And you can tell her where she can go with little Sammy’s compliments…”

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang: “I steal.”

“I think it’s the uniform I miss. It made you look… taller. And more distinguished.”

Those are among the first words Jim Allen hears when he returns from World War I. After an eternity spent fighting in the dirty, bloody trenches and with dreams of industry and conquest in his eyes, his childhood sweetheart, Alice (Sally Blaine), has already articulated what everyone in the picture will think of him. He’s a good man, who’s done good deeds. But if he doesn’t look the part, then he’s less than nothing and deserves to be treated as such.

Jim is the worst thing a man can be after the First World War– a dreamer. Shaken out of his sleepy routine as a shipping clerk during the war and pushed into engineering, he falls in love with the idea of designing and building things. He tells as much to his fellow returning soldiers (“We’ll be reading about you in the newspapers, I bet!” smiles one of his compatriots, in a sad bit of foreshadowing) and eventually confesses his desires to his mother (Louise Carter) and stuffy brother, Reverend Allen (Hale Hamilton). When the Reverend charges him with being ungrateful for not wanting to return to his pre-War routine, Jim lets out a speech of frustration that must have seemed similar to a lot of the audience about how he’d been given the world and then told to return to his tiny life as if nothing had happened:

“No one seems to realize that I’ve changed! That I’m different now! I’ve been through hell! Folks here are concerned with my uniform. How I dance! I’m out of step with everybody. For a little while, I was hoping to come home and start a new life. To be free. And again I find myself under orders in a drab routine. Mechanically, worse than the army. And you, all of you, doing your best to map out my future. To harness me, to lead me around, to do what you think is best for me. It doesn’t occur to you that I’ve grown! And I’ve learned that life is more important than a medal on my chest or a stupid insignificant job.”

War changes people. And I don’t just say that some veterans return broken, but it expands people’s horizons as cultures collide. They realize how big the world is and it can give them a new sense of purpose. Unfortunately for Jim, he’s returned to a country awash in young soldiers, many of whom also seeking a change in position.

Jim’s quest across the country for an opportunity to build leaves him penniless and jobless. He crisscrosses from one state to another and ends up in a flophouse in the deep South. One greasy cohabitant offers to take him to a restaurant where they can beg the proprietor for a hamburger. There, Jim’s long quest is almost worth it as he sees that piece of meat hit the grill and licks his lips… only to realize that the man who brought him there was just looking for an accomplice while he robs the place.

A gunfight breaks out and Jim is arrested, though he’d been an unwilling participant. An unsympathetic judge sentences him to ten years of hard labor, and he’s sent to join the titular chain gang.

Life in the chain gang is brutal. Prisoners are treated worse than animals, a point illustrated plainly as Jim sees the mules given the same amount of respect and dignity as they rise before dawn. He’s smacked for not knowing the routine. He’s punched in the face for wiping his brow in the hot sun. The warden and guards deal entirely in humiliation, feeding them grease, working them for 15 hour days, and then beating anyone who displeases them. It’s the system built to satisfy a sadist, and the prison staff is bleeding with them.

“Well, there’s just two ways to get out of here. Work out. Or die out.”

Jim is back fighting another war, this one over his dignity. It’s all pretty sensational stuff, and unerringly cruel. John’s fellow inmates include people of all stripes and color stuck in for any kind of crime, from murder to Jim’s case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

John counts down his time left one month in and realizes the sad truth. He can’t last. Among his fellow inmates, Bomber Wells (Ellis) is the most notable, a surrogate father figure for Jim and the closest thing to a friend he’s got. When Jim despairs, Bomber gives him the straight dope. People can escape. The only catch:

“You gotta beat the chains, the bloodhounds, and a bunch of guards that’d just as soon bring you back dead.”

Bomber tells him that the only way to get out was to look for a weakness and bide his time until then. Months pass as he plots, and he finally knows the gang’s routines well enough to make his move. Enlisting the help of Sebastian (Everett Brown), the big black man who they keep in jail because of his sheer strength, Jim gets his anklets bent. A few days later, when the timing is right, Jim uses a bathroom break to make his move and dashes into the woods.

The escape sequence is excellent at creating tension by never precisely illustrating the distance between just where Jim and his pursuers are. It’s not disorienting enough for the chase to seem like a cheat, but just a little bit of visual trickery to make the audience unsure. Is he only a few feet ahead? Or has he got time to change his clothes? The chase climaxes with Jim using a reed to hide under a pond with the guards mere feet away from him. It’s beautifully modulated.

Despite a massive manhunt and a few close shaves (almost literally), he hooks up with fellow former con and continued crook, Barney (Jenkins), who sets him up for the night. That includes a woman named Linda (Noel Francis), who helps overcome his shyness and shame of being a convict through both empathy and, well, you know.

The first thing Jim does on the outside is get himself a new set of clothes. The new outfit seems to make him impervious to suspicion, and, after a train ride north, he finds himself with a job in Chicago, doing exactly what he’d dreamt of. He meets a pretty landlady named Marie who clearly wants him to board with her. Life seems to be going well (even if his new nom de plume is simply his name reversed– Allen James) until Marie discovers his secret and blackmails him into marrying her. While his star rises and he becomes a big time engineer, she spends lavishly and runs around with other men.

Things come to a head when Jim falls for a sweet girl named Helen (Vinson). Marie calls the cops, and he’s soon embroiled in drama as the Governor of Illinois resists sending him back to Georgia, especially once Jim’s accounts of life on the chain gang start getting published and making headlines nationally.

There’s a meeting between Jim and officials from Georgia and Illinois. Georgia offers Jim a chance to clear the air: he stays in prison for 90 days as a clerk and then can expect a full pardon. He leaves the room and consults Helen about it as he just wants to get the books cleared with the state, but his lawyers and the other Illinoisan officials are dubious. The movie rogers the audience a bit by cutting back into the room before Jim reenters, showing the Georgian official proselytizing his own beliefs in the chain gang system:

“Our chain gangs are beneficial to the convicts. Not only physically, but morally.”

Were Jim in the room when he said that, there’s no way he’d have gone back. But he does, and it turns out that the penal system of Georgia is more than happy to lie to him to force him to fulfill the rest of his ten year sentence. They dangle that pardon over him and send him to the worst prison in the state, eager to break him just for defying the system both physically (in the escape) and spiritually (in his personal success).

Jim is horrified as he realizes he was tricked. His brother, the Reverend Allen, still plays the pragmatic role, believing as he did in the beginning of the movie in the sacredness of institutions and the importance of blind faith in them. (It’s no wonder he’s a reverend.) As the Reverend sits comfortably outside the cell, handing his brother platitudes even as the 90 days evolves to a full year, Jim is livid. He shakes the bars as he yells at his placid brother:

“The state’s promise didn’t mean anything. It was all lies … Why, their crimes are worse than mine! Worse than anyone else’s here! They’re the ones that should be in chains, not we!”

Spoilers.

He makes it through another year in the system, but it’s perfectly clear that the parole board has no intention of letting him out of their clutches again. Bomber, who’d also been sent to the new prison, helps hatch a plan with Jim to break free. They steal a truck and are pursued by a pack of guards, with Bomber mortally wounded as they wind through the dirt roads.

It’s definitely no coincidence that Jim’s final act of defiance is blowing up a bridge since bridges are a huge symbol in the film. Seeing one from his office window at the beginning of the film sets Jim out on his journey of self-discovery. On the chain gang, he’s helping to assemble a bridge when he makes his escape. At his peak in Chicago he’s planning and building new ones, and that seems to be the only thing that brings him joy in life. And then, at the end, those sticks of dynamite.

Bridges represent progress– a hope for the future, a connection of people and ideas, all while being massive feats of imagination and mathematical planning. Making them the fruits of Jim’s ideals is smart, as it pegs him as a dreamer, someone whose desires are inherently good for the world. When that final explosion hits the screen, it’s not just Jim escaping bondage, but separating himself from all his hopes and dreams.

The film’s final shot has been talked about everywhere for practically any reason. It’s unsettling and unnerving. Even at his most desperate and frustrated, Muni’s Jim had maintained a sense of dignity and pride. At his lowest points in the chain gang, he gritted his teeth and planned for his victory and freedom.

All that is gone as the epilogue begins, a year after the bridge is blown and his second escape. He hides in the shadows waiting for Helen to reappear so that he can say his final goodbye. She begs him to stay, and promises that she’ll fix things. He’s not listening– every noise puts him on edge. He’s like a caged animal, frantic and mad.

“But I haven’t escaped! They’re still after me. They’ll always be after me!”

Because now he knows he can’t escape. He can’t trust the system. It gave him a bad break before, and had the chance to make up for it. Instead, the whole system was petty, vengeful. There’s no hope in a system that simply seeks to destroy its own for its own satisfaction.

The irony that the previously innocent Jim has had to turn to crime to stay alive is especially poignant. The system wins, and, through tyranny and cruelty, creates exactly the kind of criminal it wanted all along. The movie notably doesn’t give a single person the screen time to make them overwhelmingly represent the Georgian penal system– even David Landau’s prison warden only appears in one scene and doesn’t even get named– effectively creating a boogeyman of an institution, impervious to the strength of just one courageous man, but only for so long.

End spoilers.

Is the movie still relevant? Do you have to ask? It’s a fascinating flick, and a perfect discussion piece between the two prevailing schools of thought on modern American prison practices. One is that the purpose of incarceration is to reform the prisoner, give them the opportunity to realize the errors of their ways and a second chance for a crime free life. In fact, this is what the Georgian officials use to argue for the effectiveness of the chain gang system– hey, Jim was a big success in Chicago, so it must have been Georgia’s great reformatory system that made him so.

Mind you, that idea of reform is usually a cover for the more predominate school of belief that prison time is meant as punishment for the perceived wrongs that the criminal has committed. That’s why the state of Georgia, so insistent that it’s reformed him into a model citizen, still wants him back. Because he slighted them both in success and by calling them out on their depravities, there must be a consummate degradation.

The moral universe of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang is one entirely built out of self interest. Jim earns our sympathies because he’s the only one whose self-interest is linked to helping others. The system harbors a deep distrust of dreamers like him or anyone who doesn’t functionally fit into the prescribed social roles that Jim so indelicately left at the beginning of the film. The poor and displaced are put in prisons where they’re left to serve as puppets for their jailers amusement. The world of I am a Fugitive is what happens when justice is removed from the process.

After the initial musical boom and their gangster movies, I Am a Fugitive helped to redefine Warner Brothers and the kinds of movies they made. I Am a Fugitive led to a slew of films from Warners that took on contemporary problems, including The Mayor of Hell, Heroes for Sale, and Wild Boys of the Road. Their greatest success during the early 1930s, in my book, is a combination of a hard luck slice of life and the Busby Berkeley musicals that kicked off the rebirth of that genre– The Gold Diggers of 1933.

Gold Diggers shares director Mervyn LeRoy, who made too many ‘okay’ movies to ever be considered one of the great ones but just enough great movies to be worth discussing. The pre-Code era was his most prolific time, as he helmed Little Caesar, this film, Gold Diggers, Three on a Match, Five Star Final and Heat Lightning all within a few years of each other. He was one of Warners’ more ambitious directors in terms of both style and substance and typified their ethos as a studio that pushed boundaries. He did have a bit of comeback later in his career with Quo Vadis and Mister Roberts as well.

I am a Fugitive captures one of LeRoy’s predominate themes, focusing on ‘the forgotten man’ who would soon be immortalized in one of the most famous production numbers in the early talkie history. Jim is a ‘forgotten man’ and is important as a symbol of not just the state eating its own, but destroying those who’ve served it. The movie’s most poignant moment may remain the scene before Jim gets in trouble and sent to prison. Desperate for food in St. Louis, he tries to pawn a military medal only for the pawn broker to show him a case full of them.

The movie itself was released in the heights of the Depression and only a few months after the infamous Bonus Army march that characterized the cluelessness of Herbert Hoover and remains one of the saddest episodes of American cruelty towards its own. Tens of thousands of unemployed veterans marched into Washington to ask for an early redemption of their bonuses promised to them after the First World War, and Hoover responded by sending in the military to disperse them. It resulted in several deaths. There was a palpable sense in the country that the government had abandoned its connection to its citizen and was turning into an unchecked monster.

That paranoia and sadness feeds into I am a Fugitive, and creates one of the hallmark films of the pre-Code era. It’s a plea to be heard, a cry for help in the darkened theaters across the country. It’s a lightning bolt that isn’t just about reforming the corrupt system of punishment for one state, but reminding people to take a had look at the entire apparatus of government and remeber that the government is there to help them, not the other way around. I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang created a firestorm in 1932, and has lost none of its fierce power since.

Gallery

Hover over for controls. Right click and choose view image to see it in its full size glory!

Trivia & Links

- Based on a true story, and though liberties are taken to up the film’s dramatic thoroughfare, it’s surprisingly close to reality. Robert Elliott Burns was a World War I vet down on his luck when her participated in a restaurant robbery in Georgia that netted a little over $5. He was sentenced to ten years hard labor on the chain gang, but escaped by getting his shackles bent just like in the movie. He moved to Chicago where he became a famous editor and speaker before his bitter, gold digging wife gave him up to the authorities. He was promised clemency if he returned, but, just like in the movie, the parole board refused to let him go and planned to force him to finish the rest of his sentence. He escaped again after a year (not as dramatically as shown in the picture), and hid out in New Jersey. Burns wrote his account of his time on the chain gang and it was serialized in “True Detective Mysteries.” Warner Brothers paid $12,500 for the film rights and even hired him as a consultant for the film under a pseudonym. He was paranoid, though, and didn’t stay long in California. He was caught in New Jersey shortly thereafter and… well, I’ll let AMC Film Site pick up from there.

Only three weeks after the film was released in mid-November, 1932, Georgian officials learned of his whereabouts in New Jersey and arrested him as a fugitive. Governor A. Harry Moore, the first of three NJ governors, officially refused to extradite him.

At the same time, the milestone film received the year’s Best Film honor from the National Board of Review. Newspapers in Georgia were in an uproar over the endorsement, carried headlines such as YANKEE LIES, and two prison wardens sued Warner Bros. for libel in the film (their suit was dismissed by the Fulton County Superior Court).

Eventually, reform of the chain gang system was successful. By 1937, chain gangs had been outlawed in Georgia. In the mid-40s, Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall proposed to be Burns’ lawyer if he would return and settle the matter. Burns voluntarily and courageously returned to the state in 1945, where the Georgia Pardon and Parole Board commuted his sentence to time served and restored his civil rights. But he was not officially given a full pardon (because he had admitted being guilty for the holdup).

- Scott McGee, TCM’s Head of Program Production, really likes this one as you can see on the movie’s TCMDB page which features a half dozen entries all credited to him. There’s some rather great trivia there (highest grossing American film in the Soviet Union at that time!) but I’ll pick the two pieces that made me perk up the most. First, for anyone who bemoans studio executives and how they ‘ruined’ films, you have to understand that I Am a Fugitive was pretty much Warner Brothers Production Chief Daryl Zanuck’s baby.

Despite Jack Warner and Darryl Zanuck’s personal interest in a film version of I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, the Warner Bros. story department voted against it with a report that concluded: “this book might make a picture if we had no censorship, but all the strong and vivid points in the story are certain to be eliminated by the present censorship board.” The story editor listed specific reasons for not recommending the book for a picture, most of them having to do with the violence of the story and the uproar that was sure to explode in the Deep South. In the end, Warner and Zanuck had the final say and approved the project.

- The excellent book The Genius of the Studio actually covers the entire process that went into creating the film, from beginning to end. Here’s just a snipet, talking about Zanuck, who crafted the movie to be Warner’s big critical success for the year and refine the studio’s message.

Zanuck was directly involved in shaping [the Warner Brothers’ style], not only through script development and production design but also in his involvement on the set. Unlike Thalberg, who fashioned MGM’s style from his office and cutting rooms, Zanuck was on the set constantly, often providing counsel regarding a camera angel or a story problem.

- Thomas Doherty’s essential Pre-Code Hollywood quotes Jack Warner as saying that I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, “will make us some enemies.”

- But back to McGee’s piece at TCMDB, this paragraph, about Muni’s dedication to getting the movie right, is nuts:

Mervyn LeRoy was assigned to helm I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, even though he was then preparing to direct the musical 42nd Street (1933). LeRoy agreed to abandon 42nd Street temporarily (Lloyd Bacon eventually took over directing the milestone musical), and immediately took a train to New York City to see potential star Paul Muni in the stage play Counselor-at-Law. After Muni’s performance, LeRoy wired the studio executives: “This is our man!” But Muni was not as impressed with LeRoy upon first meeting him in Jack Warner’s Burbank office. Warner made the introductions, but Muni did not say anything to LeRoy. Instead, he turned to Warner and said, “Is he the director, that kid?” Despite that inauspicious beginning, the director and the star became close friends. When Muni died in 1967, the only two people from the film industry present at his funeral were LeRoy and Muni’s agent.

Once Muni was hired for the lead role in I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, he booked passage on an ocean liner through the Panama Canal to Los Angeles. Aboard the ship, Muni spent much of the thirteen days of the voyage in his stateroom, memorizing his lines. This was not the last measure of Muni’s role preparation. He conducted several intensive meetings with Robert Burns in Burbank in order to capture the way the real fugitive walked and talked, in essence, to catch “the smell of fear.” Muni also set the Warner Bros. research department on a quest to procure every available book and magazine article about the penal system. Muni also met with several California prison guards, even one who had worked in a Southern chain gang. Muni fancied the idea of meeting with a guard or warden still working in Georgia, but Warner studio executives quickly rejected his suggestion. Nevertheless, Muni’s insistence on realism enhanced his performance; during the grueling rock quarry scenes, Muni refused to allow the use of a double, despite the punishing 5 a.m. start time and the mid-day July sun. The intense sun was so severe that nearly the entire company suffered from eyestrain, blisters, and sunburn.

- The Mythical Monkey believes that Paul Muni should have taken home the Oscar for the year between his performance here and in Scarface. He explains about the lead actor:

Muni was born Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund of Polish-Jewish decent in what is now Lviv, Ukraine. In 1902, at the age of seven, he immigrated to the United States with his parents and came of age in New York. Muni learned the craft of acting in what was then known as “the Yiddish theater,” and because he was so skilled at the art of makeup, he was dubbed “the New Lon Chaney.”

Despite being nominated for an Oscar, Muni’s first screen performance, 1929’s The Valiant, was a box office failure. When his second film was also a flop, Muni returned to the Broadway stage and didn’t make another movie until writer Ben Hecht recommended him for the lead in Howard Hawks’s gangster classic, 1932’s Scarface. When he followed that box office smash with an Oscar-nominated performance in I Am A Fugitive From A Chain Gang, his Hollywood career was set. In the course of a career that ran until his retirement in 1959, he was nominated for four more Oscars, winning in 1936 for The Story Of Louis Pasteur.

Today, opinions about Muni’s abilities are split, with many critics echoing British film historian David Thomson who calls Muni “awful” and “a crucial negative illustration in any argument as to what constitutes screen acting.” Me, I’d call him “theatrical”—he worked like a Method actor, immersing himself in a role, but he learned his technique on the Broadway stage and despite years in Hollywood, never strayed far from his origins.

- Cliff at Immortal Ephemera recommends Muni lovers check out Actor: The Life & Times of Paul Muni and adds how 1932 was a breakout year for the actor:

The studio Muni would most famously be associated with came calling next when Warner Brothers presented him with what would eventually be called I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. This classic would be filmed during July-August 1932 with Muni returning to New York September 12, 1932 to pick up the part of George Simon again back at the Plymouth where Counsellor-at-Law would run for yet another 104 performances before touring other American cities. Chain Gang would open in New York in November 1932 where it replaced the long-running Scarface at The Strand. “Muni was to replace Muni there,” (181) wrote Lawrence, while the New Yorker could also go see Muni in the flesh in Counsellor-at-Law through May 1933.

How about that period for the making of a star?

- The DVD release of this includes a commentary by USC professor Richard B. Jewell and a comedy short called “20,000 Cheers For the Chain Gang”. I don’t have the DVD, but reviews I’ve read praise the commentary track and seem baffled by the short. From Digitally Obsessed:

The short 20,000 Cheers for the Chain Gang spoofs two of Warner’s most popular prison dramas of the day—I Am a Fugitive and 20,000 Years in Sing Sing—while also taking a few pointed jabs at director Busby Berkeley. The plot concerns the tough-minded warden of a Southern chain gang, who, after learning a committee will be investigating the appalling conditions at his prison, decides to pull the wool over the inspectors’ eyes by “redecorating” the barracks, improving the food, and hiring a bevy of dancing girls to entertain the inmates in the mess hall. The stunt works so well and receives such positive press, a quintet of knucklehead convicts who recently escaped from the joint fall hook, line, and sinker for the scam. They come to believe life on the inside sure beats the nagging wives and everyday pressures of life on the outside, and they hatch a scheme to break back into prison! Though incredibly silly (and a little tasteless), the 20-minute short possesses some amusing moments and a gleefully irreverent tone.

- A few posters and more screenshots from DVD Beaver, and some great lobby cards at Doctor Macro.

- Mick LaSalle in Dangerous Men rather succinctly (and brilliantly) lays out the film’s view of morality, as well as how Warner Brothers viewed theft in many of their pre-Code offerings:

Based on the autobiographical book by Robert E. Burns, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang took one man’s hard-luck story and turned it into a treatise on how contemporary America could wreck a guy. First send him to war. And if that doesn’t kill him, stifle any impulse he has for a rewarding existence. If that fails, set him loose in an economy in which there’s no work, then rig the political justice system. And, finally, create prisons designed to kill people if they stay and kill them if they try and escape. In I am a Fugitive, few things connected with authority have any value or integrity– even the church, or at least that’s implied. The protagonist’s brother, a well-meaning minister (Hale Hamilton), gives him nothing but bad advice and eventually commits an indiscretion that sends him back to prison.

In pre-Code Depression films, moral precepts took a backseat to practical necessity. It might be criminal to blow up a bridge, but some things just have to be done. Likewise, hungry people were not expected to starve rather than steal. Like Saint Thomas Aquinas, the films saw nothing immoral in a hungry person’s taking food in order to keep body and soul together (as Joan Blondell does when she steals two hot dogs for herself and her boyfriend in 1932’s Central Park). The moral license granted by the Depression resulted in outrageous behavior in many films.

- Angela from The Hollywood Revue calls this one ‘Essential’ and surmises:

Everybody should see this movie at least once in their lives.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- Awarded best picture by the National Board of Review in 1932.

- Placed in the National Film Registry in 1991.

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 Comments

keri · June 26, 2015 at 11:31 am

This was an excellent review, Danny. I saw it for the first time myself just last autumn when it was double-featured with COOL HAND LUKE, and I was really hit by how much I AM A FUGITIVE felt just as fresh and modern as COOL HAND LUKE, despite being 30 years older, and that one is over 40 years old now!

Danny · July 2, 2015 at 10:07 am

That would be a really interesting double feature, for sure. Thanks for reading!

Dennis H. · June 11, 2016 at 1:05 pm

Just saw this for the 1st time last night. Magnificent. It is INCREDIBLY powerful, and it holds up surprisingly well. Do not miss this film.

Jonathan · September 13, 2016 at 9:27 am

Huh. I’m genuinely surprised that the gold-digging wife turning him into the authorities was part of the true story.

srogouski · December 24, 2016 at 5:04 am

One of the best, most radical American films ever made, maybe the one time American cinema approached the revolutionary potential of the medium.

randy acuna · February 11, 2017 at 1:44 pm

should be on every serious classical movie fan’s list . at least in there top 10 to 15th . i know how hard this can be but , this film is exceptional . a timeless classic which when viewed today is still fresh and powerful .

Deborah Williams · November 30, 2020 at 8:25 pm

love this movie.

Comments are closed.