During the evening, [actor Robert] Morley asked Norma, “How did you become a movie star?” Too late he realized how tactless the question sounded, as if she failed to correspond with his image of a star. But Norma didn’t take it that way. She smiled and said, “I wanted to!” with a directness that settled the matter.

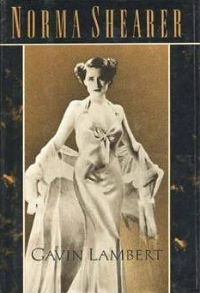

– Norma Shearer by Gavin Lambert, page 260

Norma Shearer, more than perhaps any other actress, became a star by sheer force of will. Born in 1902 in Montreal with a cast in her eye and a family with a history of mental illness, Shearer announced her intentions to be a star at an early age. After her father lost the family business after the end of the first World War, Shearer’s mother, Edith, took Norma and her older sister Anathole to New York City. Despite having both D.W. Griffith and Florence Ziegfeld pronounce her dreams of being a theatrical star as impossibilities, she used their doubts to redouble her efforts. She worked out, retrained her eye, and began to do modeling before a small movie company took notice and put her in pictures.

A string of poverty row cheapies eventually brought her to the notice of “Golden Boy” Irving Thalberg, who first at Universal and then MGM attempted to and finally did land Shearer’s services. At MGM she quickly made waves in a series of pictures with Monta Bell and became a prime moneymaker for the nascent studio throughout the mid-1920s. When sound rolled in, MGM was the last to adopt. However, Shearer had her voice tested and was declared to have the perfect voice for talkies– one imagines if she hadn’t, she would have very quickly have made it that way.

After a long courtship, Norma Shearer married Thalberg. Less a marriage of romantic passion but of two people who respected and depended on one another, the alliance between the head of production at MGM and its second biggest star (after Garbo) seemed fortuitous save for one thing– Shearer and Thalberg had extremely different ideas of what a Norma Shearer picture should be.

Shearer wanted complicated, intelligent material, and in 1930 swiped the lead role in The Divorcee out from under Joan Crawford’s nose. (Crawford would get her revenge years later for many parts lost to Shearer by being a complete asshole to her during the filming of The Women in 1938.) Thalberg hadn’t believed his new wife could play ‘sexy’, so to convince him to give her the part, Shearer contacted photographer George Hurrell and had a series of pictures taken that showed her lounging in kimonos and amplifying her legs. The ploy worked, getting Shearer the part that would earn her an Oscar and Hurrell a job working for the studio.

The Divorcee was a turning point for the talkies, taking on weighty and controversial material with a sense of elegance and style. Shearer’s next movies cashed in on the film’s success to varying degrees, but Thalberg’s health problems soon interrupted her creative streak as the two vacationed to Europe in 1933 to help him recover. During that time, Thalberg pressed upon Shearer the idea that she had to make prestigious pictures to become the perfect American actress, pushing her away from her sexy ‘Divorcee‘ image and towards more lavish dramatic films like Romeo and Juliet and Marie Antoinette.

Thalberg’s death in 1937 put Shearer in a precarious position, and her films after Marie Antoinette, save for The Women, struggled. Without Irving around, she lacked a focus in picking projects, passing on opportunities like Now, Voyager and Mrs. Minivier because she felt they were outside her image. Her last two movies were flops, and she decided to fade away rather than stick around. She remained obsessive with adapting F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon (based on thinly veiled versions of Thalberg and Shearer), first with Tyrone Power in the late 30s and then with Robert Evans in the 1970s.

Shearer discovered Evans, who would go on to become an infamous producer and run Paramount in the 1970s, as well as starlet Janet Leigh when she saw her picture at an Aspen ski club. Shearer married ski instructor Martin Arrougé after they met in Sun City, Idaho, and they often traveled between Idaho, Lake Tahoe, and Los Angeles. As Shearer’s social circle collapsed as many of her old friends passed on in the 60s and 70s, she became a hermit. Shearer wrote an autobiography, but everyone who read it found that she’d removed any struggle or negativity, and, after the cool reaction, Shearer decided to shelve it. She was terrified of being seen in public without her makeup and still worried about how her public would see her, despite it being nearly 30 years since her last picture.

Her mental health deteriorated as she entered her late 70s, and she was placed in the Motion Picture Country Home. Shearer passed away in 1983, and her body was placed in the same tomb as Thalberg.

Norma Shearer’s Pre-Code Filmography

- The Divorcee (1930)

- Let Us Be Gay (1930)

- “The Stolen Jools” (1931)

- Strangers May Kiss (1931)

- A Free Soul (1931)

- Private Lives (1931)

- Strange Interlude (1932)

- Smilin’ Through (1932)

- Riptide (1934)

- The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934)

Studios

Videos of Norma Shearer

Video tribute to her career features clips from many of her films:

Film critic Mick LaSalle (who writes about Norma extensively in Complicated Women) talks about her life and career at the beginning of this clip:

I won’t lie, I watch this video every Veteran’s Day. Norma Shearer pitches for the USO:

Norma Shearer Biography

|

Norma Shearer

|

Norma Shearer Sites and Links

Other Actresses

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

|