|

|

|

| Tom Powers James Cagney |

Gwen Allen Jean Harlow |

Matt Doyle Edward Woods |

|

|

|

| Mike Powers Donald Cook |

Ma Powers Beryl Mercer |

Mamie Joan Blondell |

| Released by Warner Brothers | Directed By William A. Wellman | ||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Our hero is a thug and he’s punished for his actions. But, boy, it looks kinda fun up to that point.

- Oh yeah, they’re gangsters and booze runners who hit up plenty of speakeasies.

- “Lizzy Jones, big and fat, slipped on the ice and broke her [prat].” (Thanks Phoebe!)

- The main character kills a cop and a criminal who spurned him when things got tough. He gets away with it both times.

- A fey dresser ignores Tom’s request for more room in his trousers and instead compliments his bicep.

- Tom and Mike run around with a couple of girls outside of marriage at a hotel to a wee bit of scandal.

- Some poor woman gets smacked in the face with a grapefruit.

- Harlow’s Gwen has ‘known’ dozens of men.

- Dude revenge kills a horse.

- Tommy’s boss’ girl tells him that she wants to “do things for you, Tommy” and then proceeds to rape him.

- The film’s ending, while certainly a brutal punctuation mark, doesn’t leave things as tied up as neatly as one would expect.

The Public Enemy: Getting Up in the World

“Tommy, I don’t want to die!”

“Oh. So you don’t want to die.”

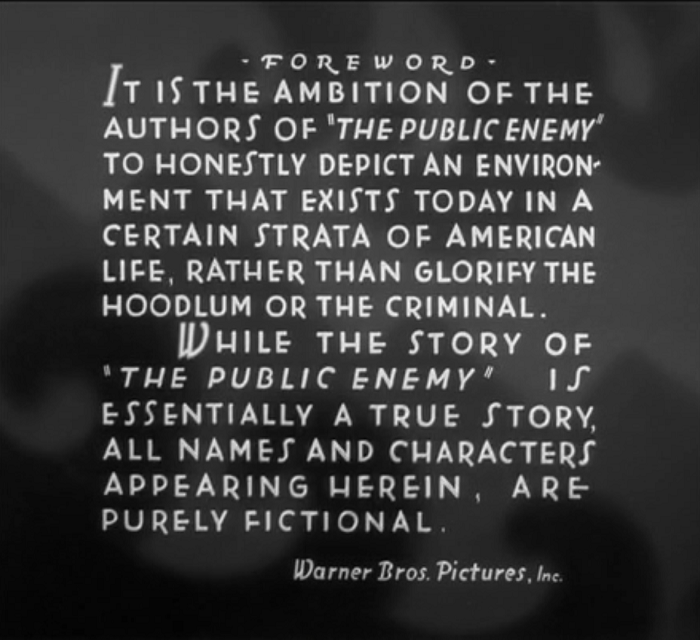

My favorite thing about 1931’s Public Enemy is easy to point out, mostly for the fact that it occurs during the film’s opening credits. Just a moment or two after the title card and before we even get to the preamble where Warner Brothers tries to whitewash the film’s violence by claiming to merely be a documentation rather than an exultation, we get James Cagney’s film credit.

Just look at this mug:

If you want to know why The Public Enemy made him a star, it’s all right there. Director William A. Wellman’s brilliance in eschewing the normal title clips (usually culled from moments in the film) for these brief moments with the characters is an immediate game changer. When Jean Harlow and Joan Blondell smile at the camera a few moments after one another, it’s not them smiling for an appreciative audience, it’s to each and every audience member who wouldn’t mind getting a smile from either of those ladies.

Cagney’s introduction, while missing the sexual component (we’ll certainly get to that later), is playful. He’s wearing the deliveryman outfit that signifies his lower class job, but has that devilish smile combined with the eyebrow waggle that indicates that this is just part of something akin to a ruse. His teasing air punch is further indication that he’s palling around, an invitation to the audience to come and have some fun with him.

The Public Enemy is, of course, a lot of fun. It’s a roller coaster about the life of an unimaginative thug and his rise and fall, from the trappings of the noveau rich to his failed attempt at a blaze of glory finale. The movie made James Cagney a star, his dominating energy pulsating through the films 84 minute run time. If you look away from Cagney for a second, you’re at risk of missing something. A wink, a smile. For a lot of actors this would be blatant scene stealing, but, for Cagney, this is his character’s commentary track, a non-stop gab about how Tommy sees the entire world that’s completely silent to the ear.

Boy, having guns is great!

Those articulations shine through in the film’s opening credits, too. The opening music, both wistful but playful, sets the stage for a lengthy flashback showing how Cagney’s character, Tom Powers, grew into a sociopath. The answer is, naturally, he wants to sleep with his mother.

Okay, okay, we’ll just say that he has an Oedipal Complex so you don’t have to think too much about it. But his kind, pleasant, and aggressively sympathetic mother is always there in his life, and he spends most of it lying to her or otherwise trying to make her happy. He offers her money and every nice thing he’s got, which is summarily refused on her behalf, first by his silent and stern policeman father and then by his older brother, Mike. Tommy is powerless against both of them– even bookworm Mike can take him down in a single punch– and this frustration only feeds into his need to find some degree of strength in his own life. Rebelling against not just their authority but all authority seems like the perfect way to do it.

Rebel With an Icky Cause

This rebellion begins early on in his life. He spends his afternoon at a boy’s club whose main activities are dirty songs and petty larceny. We also see Tommy and his sidekick, the bland crony Matt, enjoy some beer from a paint bucket when both are barely in their teens. They like pushing people around, and, even when this results in a beating from his father, Tommy only grits his teeth. Next time he’ll do something bigger.

Tommy gets older, and that look of glee Tom gets when he receives his first pistol is almost dangerously infectious. There’s a raid on a fur warehouse where he panics at the sight of a stuffed bear and causes one of his gang members to get killed. While running, Tommy and Matt are cornered by a policeman. They kill him, further driving home the oedipal issues Tommy seems cursed with– his father was a cop too, after all. The gang turns their back on him, and he promises revenge.

Tommy’s handy work.

Tommy and Matt learn their lesson: everyone is bigger and stronger than you, so you have to play like you’re bigger and stronger to get anywhere.

Luckily for the two, petty crime is about to go big time. Enacted in 1920, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution created a nationwide prohibition on the sale of alcohol. This opened a big hole for bootleggers to come in and rake up big profits with piss poor products so long as they had enough muscle to bully their competition, all the while staying a step or two ahead of the law. For someone as brazen as Tommy this is the perfect racket, and soon he and Matt are well paid enforcers for a big time bootlegger.

Tom’s love life takes a tick for the better as well, playing hanky panky with a dame named Kitty in a slinky hotel. But Kitty wants a commitment and offers it to Tom in the most passive-aggressive way. He grows frustrated and distrusting of her neediness and, instead of voicing his dissatisfaction, he places a grapefruit in her kisser. The scene is often cited as comedic or dynamic, but its really an encapsulation of all of Tom’s inability to express himself in any way outside of violence. Kitty slouches back, stunned, and the moment ends with her silent and dejected. Tom doesn’t know it, but it’s one of the defining moments of his life; he’s just a scared kid who can’t communicate.

Those two guys passed out having a drink with Joan Blondell and Mae Clarke– making them probably the biggest suckers in the history of movies.

This is reflected in his family dealings as well. His father is gone, never to be mentioned again, but Mike is back from his service in the first World War. He’s clearly a bit shell shocked by the experience (or suffering from PTSD to use modern parlance) and is horrified when he discovers that Tommy is running booze. Tommy spits back that killing men in the trenches is no different than being a hood in a gang war– a willful ignorance that horrifies Mike, especially once Tommy accuses him of enjoying the kills he committed. This confrontation only further pushes Tommy towards crime, breaking his poor mother’s heart.

Tommy is the model lackey: smart but not smart enough to push for more money. Tom takes rather than gives– in the bedroom too, apparently. After ditching Kitty, he picks up Gwen, a high class escort who finds Tommy’s blunt nature and forthright desires to be a godsend. She explains it succinctly:

You are different, Tommy. Very different. And I’ve discovered it isn’t only a difference in manner and outward appearances. It’s a difference in basic character. The men I know – and I’ve known dozens of them – oh, they’re so nice, so polished, so considerate. Most women like that type. I guess they’re afraid of the other kind. I thought I was too, but you’re so strong. You don’t give, you take. Oh, Tommy, I could love you to death.

Unfortunately, just when it’s time for them to consummate their relationship to death, Tommy’s entire world turns upside down.

“Let me clasp you firmly to my unconsummated bosom.”

Going Out, Guns Blazing (Or Not)

Spoilers for this next section.

The death of Nails, the mob boss Tommy has been working under, sends his gang into a tailspin. Sensing weakness, other mobs start muscling in. He and Matt are holed up by a gangster pal named Paddy into his trashy apartment hosted by Paddy’s mistress.

What happens next is glossed over in a lot of reviews, but there’s really no two ways about it. For much of the movie, Tommy’s masculinity is challenged overtly– whether from the gay fashion designer hitting on him to the attempted manipulations of Kitty. It comes to a head when Tommy gets hammered and, despite his protests, Paddy’s mistress rapes him. The next morning he wakes up hung over and is horrified. For someone who’d come close to finally realizing a healthy sexual connection to Gwen, this woman, taking advantage of him at his lowest and weakest point, destroys his romantic aspirations. Completely defeated and so revolted with the woman (and himself), he heads out with Matt onto the dangerous city streets. This is when Matt, his faithful lifelong companion, is gunned down in broad daylight, with bullets bouncing only inches away from Tommy’s head.

Tommy spent the entire movie yearning for power and love, and, just when he’d felt he had it, it’s gone in a few brief hours. The rape has left him feeling impotent, and Matt– the only person in the world who actually treated him like family outside his mother– is brutally killed. Tom responds with the only way he knows how, taking a pistol into the rainy night on his own, bound and determined to get revenge against the mob boss who ordered the hit on him in a final, sweet blaze of glory– spitting once again into the eye of his brother, family, and anyone who’d ever stood against him.

Wellman knows how to shoot a rainy night.

Wellman’s rain soaked staging of the climactic act– an atmosphere he’d perfected back in Other Men’s Women for sure– is fantastic, and the scene’s perfectly staged. There’s no speech about his suicide mission of revenge, no lengthy rationale. Just Cagney’s demonic little smile. Just like how we don’t see the final gun battle but merely hear it, Tommy’s success is irrelevant in there. The fact is that he survives his big final, terrifying spasm of violence. It’s something that he didn’t reckon on and, collapsing in the gutter, for the first time realizes what his “eye for an eye” worldview really entails.

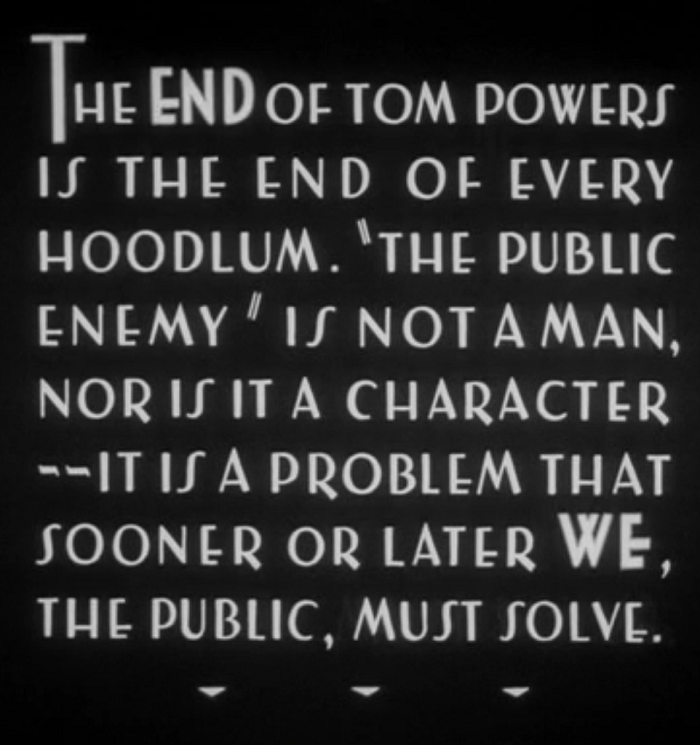

Tommy’s reconciliation with his family is overdue, but certainly comes with the knowledge that he probably isn’t going to survive his hospital stay. He doesn’t and this pays off in the film’s brutal ending where his corpse is delivered to his mother’s house by the rival gangsters. Mike opens the door as Tommy’s lifeless body falls to the floor.

There are two big questions that the ending leaves open. The first is who exactly killed Tommy: the faceless head of the rival mob? A lackey? It doesn’t really matter, but that open-endedness adds a lot to the bluntness and horror of the finale. There’s still a killer out there, another no-name hoodlum like Tommy. The cycle of violence, it seems, continues.

Again equating World War I to gang warfare, but not in a fun, happy way.

But that leads into the other question– Mike’s reaction to Tommy’s corpse falling on his living room floor. Mike’s seen death and horrors on the battlefield, and he stalks off toward the camera during the film’s last moments. He’s horrified, sure. But is he horrified to act against these gangsters in their eternal war of one upmanship? Or has this broken his own mental peace, and now its his turn to reenter his own violent nightmare?

The appeal of Tommy’s character remains that he was just a cog in the world, someone who felt the need to fight back every time an obstacle was put in his path. Americans are often taught to defy the odds and push against injustice in an unjust world. Tommy, who fought against people bigger and stronger at nearly every turn, does so with such charisma and charm that it’s impossible not to root for him no matter how rotten he smells. Cagney became a star here because he stands up to the system, and even though he dies a miserable, horrifying death, he pushes for the stars with such ferocity that it’s impossible to resist.

End spoilers.

Cagney.

Getting the Goods

Cagney’s raw, naturalistic performance is well matched by the cast, a line-up of up and comers who would soon define Hollywood’s output. Joan Blondell, for example, basically just gets to show off her smile and giggle, which ain’t a bad thing. Donald Cook would go on to a long series of minor roles, though his appearance in Wellman’s superlative Safe in Hell would be among the highlights. Mae Clarke, whose roles throughout the era involved death or other forms of unpleasant endings, would also pop up in Frankenstein among others. Jean Harlow, meanwhile, had better days ahead of her. Her performance here is fairly wooden, and it would be a few more years of acting lessons and hard work before she made a name for herself as the glamorous screwball comedienne at MGM in pictures like Dinner at Eight.

But, again, it’s Cagney who steals the show. This is only his fourth film, but already he was proving himself versatile as both heroes and criminals, all with the trademark smile and swagger. Thanks to him, The Public Enemy has stood up well over the years, even with cuts, subtractions, and the addition of numerous censor’s warnings about the content. The movie isn’t a rags-to-riches tale like you get in Scarface or Little Caesar, but the story of what made a tough guy tough. It’s about every mug who ever wanted something great and fell short. But, most importantly, it’s about that last moment, that bleak acknowledgement that gang warfare is filled with guys like Tom, and as long as there are men like that around, even the best of us are in trouble.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- This isn’t Cagney’s first gangster movie: he was the sidekick to Lew Ayres in Doorway to Hell. In The Public Enemy, Cagney was initially set to again play the sidekick crony to Edward Woods, but director William Wellman wisely switched the two men’s parts.

- Frankie Darro plays a young Matt Doyle here, and would later play opposite Cagney in The Mayor of Hell. Meanwhile, Cagney and Clarke would also team up memorably a few years later in Lady Killer, while Cagney and Blondell, who had come from Broadway together from their run in the show Penny Arcade (made into a film called Sinners Holiday), were in several more films together including Footlight Parade and Blonde Crazy. Clarke and Harlow would also appear together in Three Wise Girls, another movie that doesn’t end too well for Mae.

- The always great Richard Maltby at Senses of Cinema has an excellent essay about the film’s origins and impact. Besides detailing the real-life gangs that this film’s escapades are based on (including, yes, a real assassination of a horse), Maltby dives into the film’s reception and the gangster film cycle of the early 30s:

No one who saw Little Caesar or The Public Enemy in 1931 saw them in a cultural vacuum. Embodying the metropolitan civic corruption that had been tolerated in the 1920s, the gangster had been an acceptable representative of anti-Prohibition sentiment in the popular press until 1929, but in the cultural catharsis of the early Depression he became a scapegoat villain, threatening the survival of social order and American values. This shift in public sentiment was most conspicuously charted in changed press attitudes to Al Capone, who had ceased to be the celebrated “Horatio Alger lad of Prohibition” long before his conviction for tax evasion in October 1931.

Contrary to the mythology of a “pre-Code” cinema, the “classic gangster film” was in fact the product of only one production season, 1930-1931, and constituted a cycle of fewer than 30 pictures. The box-office success of The Doorway to Hell in late 1930 and Little Caesar in January 1931 triggered a series of imitations in a pattern typical of the industry’s exploitation of a topical cycle, but none of the pictures released after April 1931 were box-office successes. By then, exhibitors were reporting that audiences had had enough of gang pictures, while a plethora of civic and religious organisations complained that these movies continued to endow gangsters “with romance and glamour”. In response, the industry claimed that the movies were “deterrents, not incentives, to criminal behaviour”, “debunking” gangsters through “the deadly weapon of ridicule”, and stripping them of “every shred of false heroism that might influence young people”, most conspicuously through the use of ethnic stereotyping in casting and performance. After the New York censor board eliminated six scenes from The Public Enemy before permitting its release in mid-April, however, the MPPDA acted to curtail the cycle, establishing guidelines for “the proper treatment of crime” in pictures and eliminating scenes of inter-gang conflict and stories with gangsters as central characters.

The opening crawl for the curious.

- Over at IMDB’s trivia page, we get one supposed lowdown on the origins of the infamous grapefruit scene.

Several versions exist of the origin of the notorious grapefruit scene, but the most plausible is the one on which both James Cagney and Mae Clarke agree: The scene, they explained, was actually staged as a practical joke at the expense of the film crew, just to see their stunned reactions. There was never any intention of ever using the shot in the completed film. Director William A. Wellman, however, eventually decided to keep the shot, and use it in the film’s final release print.

According to James Cagney’s autobiography, Mae Clarke’s ex-husband, Lew Brice, enjoyed the “grapefruit scene” so much that he went to the movie theater every day just to watch that scene only and leave.

- TCMDB is mostly focused on the grapefruit, too, and talks about the ramifications of that scene, as well as how this film impacted Jean Harlow’s nascent career:

While it certainly stamped him with an unforgettable image, Cagney later came to regret the action. For years after, whenever the actor dined out somewhere, fans would have waiters bring him half a grapefruit with his meal. Clarke became equally weary of references to the scene, although she must have gotten a bit of satisfaction from a similar shot that caught Cagney on the receiving end of some violence. Donald Cook, who played Tom Powers’s war-shattered brother in the film, was supposed to explode in fury with a hard sock to Cagney’s jaw. In his autobiography, Cagney said he was sure Wellman had urged Cook to let his co-star really have it. Instead of faking it for the camera, Cook hauled off and belted Cagney right in the face, sending him flying across the set and breaking a tooth. Fortunately no such mishaps took place during the film’s most dangerous scenes: the use of real bullets in some of the shooting sequences. […]

As successful as the picture was for its leading actor, writers and director, it was nearly a disaster for another rising young star, Jean Harlow. Under contract to Howard Hughes, Harlow was actually a good-natured, middle-class girl most often cast as vulgar blond floozies. In The Public Enemy, she played a slumming society dame who briefly becomes Tom Power’s mistress. The picture was hailed as a sensation, with praise going to the entire cast – except Harlow. Critics slammed her for ruining the scenes she appeared in, having a voice desperately in need of training, and delivering the only uninteresting acting in the film. Although she later became a major star at MGM, hailed for her earthy comic performances, the mishandling of her talents by agents and directors in early roles like this one could have buried her career completely if not for the public interest in what was considered her greatest asset in this Pre-Code era – freewheeling sexuality and an enticing body clad in revealing, usually bra-less, costumes. Her fascinating “traits” even caught the attention of her very-married leading man. On the set one day, Cagney stared at her cleavage and asked, likely in perfect innocence and good humor, “How do you keep those things up?” “I ice them,” Harlow said, before trotting off to her dressing room to do just that.

The icy Harlow.

- Box Office Magazine‘s commentary from 1931:

This picture requires lively short subjects to brighten up the program a bit, for there is no comedy relief, and it will cast a depressing mood over the audience unless entertaining shorts are run in conjunction with the picture.

The story is absolutely serious from start to finish and was meant to be taken seriously by the audience. Unlike other gangster pictures, it shows nothing deliberate or smart on the part of the gangsters to provoke the audience to laughter. Neither does it bring politics or bribes into the picture at all. This is not for children for, although it is a good moral picture, they will not understand it. The gangsters are not paraded as fantastic figures, neither do they represent certain persons or characters but show conditions as they actually exist today; and portrays the basis for the life of crime which the gangsters lead. The story opens with the early childhood of two boys, who, through bad associates, are taught the game early in life, starting as petty thieves. After the World War and after the Volstead Act goes into effect, the two men now grown become beer racketeers, and consequently immensely rich. They are powerful figures in the racket business and force speakeasies to buy their beer or take the consequences. Rival gangs appear and one by one lose their lives at the hands of their competitive racketeers.

It is not a picture for small towns, but should be a success in large towns and cities. There is a lesson and daring truth in the picture, and we believe it was meant to awaken honest citizens to the gangster tyranny prevalent in large cities today.

- A Mythical Monkey tackles both this and Little Caesar and discusses what’s so interesting about the gangster movies of the early 30s.

A better film, less predictable and centering on an even more explosive performance, is William Wellman’s The Public Enemy. If Little Caesar is the study of an ambitious man’s rise and fall, The Public Enemy, starring James Cagney as Tom Powers, is a study of the sort of man Rico Bandello would have routinely used to do his dirty work, a small-time thug with no ambition other than to have a few bucks in his pocket and with no scruples about how to get them.

Lllllllllllladies?

- Pat at 100 Years of Movies talks about Tommy’s broken family life:

Tommy has two brothers in the movie. His real brother Mike holds an honest job, goes to night school and cares for their mother. His mob brother Matt is willing to go along with whatever the latest score is. We all know which brother Tommy is going to choose. Mike is a chump and Matt is the guy you go to war with.

- Blu-Ray.Com reviews this film’s blu-ray release with plenty of screencaps, and a run down of special features which include a commentary track and the always fun ‘Warner Brothers Night at the Movies’. Here’s a note about the movie’s origins:

The screenplay by Harry F. Thew was based on an unpublished novel entitled Beer and Blood by two Chicago natives who had witnessed Al Capone’s violent escapades in Chicago. The authenticity of detail in their source material allowed Thew and Wellman to surround Cagney’s vivid portrait of a street punk ascending the criminal ranks with the kind of specificity that Little Caesar lacked. While Cagney held everyone’s attention, Wellman’s careful staging and precise framing provided a clear explanation of how bootlegging functioned, how product was acquired, how “sales” were made with violence, how turf battles were waged and, indirectly, how the entire enterprise was a creature of Prohibition.

And the closing scrawl.

- AMC’s Film Site has the rundown, including trivia, links, and a very detailed plot description, on this enterprise.

- The Spinning Image talks about the film’s censorship issues over the years, including this tidbit:

The film runs 84 minutes, down over ten minutes from its original release because, in 1949, when the film was re-released, those minutes were cut because they featured a character based upon real life gangster Bugs Moran that were deemed unsuitable. Subsequently, that original footage has been lost.

- The movie’s trailer is pretty simple and lacks any actual scenes from the movie, but it’s hard to deny the electricity. The backing track here is “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.” (Thanks for the tip, Elizabeth!)

- Lastly, Ivan G. Shreve Jr. sums up the film and the legacy of The Public Enemy:

Nominated for an Academy Award for best screenplay, The Public Enemy did very well at the box office and earned raves from the critics, and has since become one of the seminal films in the gangster genre…a classic that was acknowledged as such when it was selected for the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1998. The cast is marvelous, the direction tight and stylish and the script has a rat-a-tat-ness that is punctuated by Cagney’s signature fast-talking style. It was the film that made the actor a force to be reckoned with… and 80 years later since its debut it remains a staple in any serious filmgoer’s education.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 Comments

brianpaige · August 15, 2014 at 1:26 am

Oh man, where do I begin? I’ve been waiting for this review for a while now, since in another movie listing I mentioned that I find Public Enemy horribly overrated. Why? Here’s my reasoning:

–The film has no flow whatsoever. I’ve never cared for films where the narrative jumps from year to year with vignettes here and there. It doesn’t really build to anything satisfying. There are memorable scenes and characters but not a memorable plot.

–Is the cast so marvelous? I dunno. Cagney is doing a 1 man carry job here. Harlow, as noted, is terrible here and Blondell doesn’t get much to do. Eddie Woods is also marginal and I am terrified of the thought of him in the lead. Incidentally, you can clearly tell they didn’t bother re-shooting the scenes with them as kids, since the Woods and Cagney kids are clearly the other role. Bush league.

–Schemer Burns? Who’s he? The film’s narrative rests on the fact that we’re supposed to care about Tom Powers and his mob vs. the Schemer Burns mob. The problem is that Schemer isn’t even in the movie! In Scarface we at least get a look at Karloff’s rival gang boss and care a bit about the character.

Anyway, that’s my two cents. But ask yourself the question: If Woods had starred in this and Cagney had been the buddy/lackey, would anyone remember The Public Enemy?

Danny · August 15, 2014 at 9:35 am

It’s okay, Brian. I read a bunch of reviews when writing articles, and at some point I just become happy when people get the facts about what actually happened in the movie right.

I agree with you on some of your points, to be honest. The opening scenes are pretty lengthy and could probably have been whittled down– though I wouldn’t lose the scene of the boys drinking beer or Tommy getting beat by his father, since those handily setup the rest of the movie. Cagney is definitely pretty much the driving force of the picture (I can’t imagine who Woods must have slept with to even be considered for the lead), though I found the switched kid actors amusing rather than aggravating.

As for your last issue, I like that the opposing mob boss is practically anonymous. While Schemer does some heinous stuff, but, like Nails, it’s not really material to Tommy’s story. It’s Tommy’s own poor life decisions that lead him to that final showdown. Tommy is the real villain of the picture, after all.

Thom Hickey · August 15, 2014 at 2:04 am

Thanks. A wonderfully comprehensive review. Lots to ponder on! Regards Thom.

Danny · August 15, 2014 at 9:24 am

Thanks for coming by, Thom!

La Faustin · August 15, 2014 at 3:13 am

Bravo for highlighting the Oedipal drama! One additional point thereto: Paddy has been a surrogate father to Tom. When the latter realizes, the morning after, that he’s slept with Paddy’s woman, Cagney has a fantastic piece of business: he’s been rubbing the sleep out of his eyes drowsily, just woken up; all of a sudden he stiffens, with his hands like claws over his eyes, as though he were going to tear them out.

About Harlow: I read somewhere that the role was originally meant for Louise Brooks. If you imagine her in the part — cool, bohemian, utterly NOT of Tom’s world — it makes a lot of sense. Harlow comes across as just the top-of-the-line version of Mae Clarke. (Also, there’s that line where Tom says something along the lines of “No one would ever believe I’d be seeing a girl this long without going to bed with her.” It makes sense for Brooks; for Harlow, I do a Dressler-style doubletake.)

Danny · August 15, 2014 at 9:24 am

Whoa. That’s a great observation! I wish I’d caught that because it makes so much sense.

As for your second observation… eh. I was just watching a movie that featured Brooks talking, and while her voice ain’t bad, I can’t say that I thought it did her any favors. While Brooks certainly personified a kind of sexy, decadent allure in her silents (especially the later ones), I can’t say that I think that talkies were her thing.

La Faustin · August 15, 2014 at 5:05 am

“Lizzie Jones, big and fat, slipped on the ice and broke her prat” (as in pratfall).

Danny · August 15, 2014 at 9:08 am

… Ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh. Thank you!

Minkette · December 2, 2019 at 9:53 pm

I…think that last word was actually supposed to be the one that begins with a T. The one that was in the addendum to George Carlin’s “Seven Dirty Words” routine.

Elizabeth · August 15, 2014 at 5:52 am

No, the music on the trailer is “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.”

Danny · August 15, 2014 at 9:07 am

Updated it above. Me and my tin ear thank you!

Judy · August 16, 2014 at 3:02 am

Great review, Danny, one of your best yet – I’m pretty much obsessed with this movie, which was the one that introduced me to Cagney, Wellman and pre-Codes, and you have done a fine job here. I don’t think I’d realised how great that little glimpse of him in the opening titles is – full of mischief. I like your take on the grapefruit scene – it now strikes me that something has gone wrong in the bedroom before this moment, and then later we learn that he hasn’t had sex with Harlow, before the disastrous sexual encounter with Paddy’s mistress which you discuss here.

Cagney is also a gangster, or at any rate a booze runner, in his very first film, ‘Sinners’ Holiday”, but he definitely ain’t so tough in that! Have you seen that one yet? He gives an amazing performance in it, though his New York accent is so strong that I could do with subtitles in some scenes!

Danny · August 20, 2014 at 11:23 am

Sinner’s Holiday is definitely on the list– in fact, I think I’m down to around a half dozen Cagney films left to cover at this point, so it’s pretty high up there!

And Public Enemy is fantastic. Can you believe Wellman followed this up with Night Nurse? … yeah, I can too. 🙂

brianpaige · August 28, 2014 at 12:31 pm

In regards to Schemer Burns, I’m not saying he needed to be a driving force of the narrative, but would it kill them to give him SOME screen time a la Karloff in Scarface? Let’s establish him as a threat if nothing else.

Jonathan · September 10, 2016 at 6:36 pm

Of all the classic gangster films I’ve seen so far, this might be my favorite. I’m so used to films in this genre glorifying its protagonists (even if just letting them go out in a blaze of glory), that this actually took me by surprise. Tommy doesn’t rise very far, his revenge is poorly planned and ineffectual (and you don’t even really get to see it), he gets no chance at redemption, and ultimately he’s just a kid who ain’t so tough. What a poignantly anticlimactic film.

rift · September 30, 2017 at 7:49 pm

Along with Scarface this possibly the greatest pre-code gangster film and for me the most engaging.

Please consider adding to your “List of Essential Pre-Code Hollywood Films”

Comments are closed.