|

|

|

| Al Wonder (no really) Al Jolson |

Liane Kay Francis |

Inez Dolores Del Rio |

|

|

|

| Harry Ricardo Cortez |

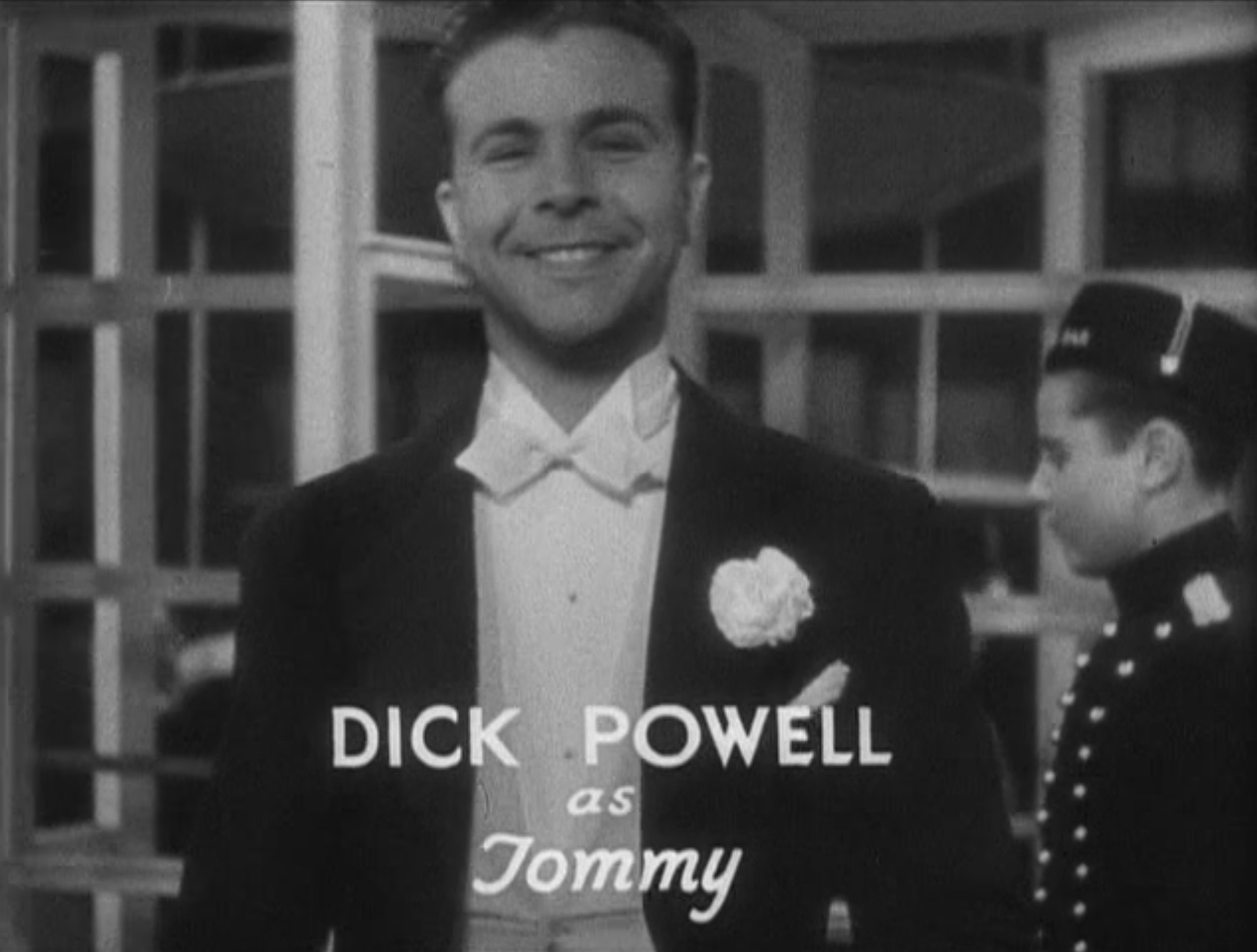

Tommy Dick Powell |

Henry Guy Kibbee |

| Released by Warner Bros. Directed by Lloyd Bacon Run time: 85 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- In easily the film’s most memorable (and controversial) moment, a man cuts in on a couple dancing and then sweeps the other gentleman off his feet. Jolson cracks with a smile, “Boys will be boys!”

- “A boudoir in America is a place to sleep. Here it’s a playground!”

- “My wife just gave birth to her fifth baby, and, I give you my word, I told her if she had another kid, I’d shoot myself!”

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you. You might be shooting an innocent man!”

- “Where have you been the last three weeks?”

“I’ve been to a nudist’s colony. But I’ll never go again!”

“Why not?”

“Well, you get tired of looking at the same faces all the time.”

- Fifi D’Orsay takes off her garter and shoots it at Hugh Herbert.

- Robert Barrat literally has a pocket knife out and tries to slit wrists at the nightclub. Buddy, I’m with you.

- “I want you to tell me if the giraffe is male or female.”

“Why should that worry you? You’re not a giraffe!”

- Guy Kibbee says “pashy pishy” and Hugh Herbert says, “Oh that reminds me” and gets up to go to the bathroom.

- A couple of the musical numbers have some risque elements, notably one in which Ricardo Cortez whips Dolores Del Rio. “He whips her, he whips her, and he whips her, but she loves it!”

- The film’s solution is rather stunning, but more on that below in the spoilers.

Wonder Bar: Nightmare Night

“There ought to be a law against bringing your wife to Paris.”

Oh boy, where to begin.

Let’s start with this: I hate Al Jolson. He is a ham, he sucks up all the oxygen in the room, he’s the star attraction who knows he’s the star. He is always at ’11’ on the dial. He makes stars like Mae West and Eddie Cantor look demure. I don’t like his singing. I don’t like his acting. And, frankly, I don’t like the person I become when I watch his films.

(Don’t let that make you think I don’t think he deserves my ire. Though perhaps I consider him beneath it.)

Make no mistake, despite the all-star cast promised on the poster and in the credits, this is Jolson’s film, acting as the sad clown savior of the central hoary drama set in a Parisian nightclub named Wonder Bar. The stakes are simple: Both Al and Tommy love Inez. Inez loves Harry. Liana loves Harry, but Liana gave Harry an expensive necklace that her husband is now sending detectives in search of. Harry has to get out of Paris, the more cash in hand the better. Harry only loves Harry.

There is are a pair of B-stories, which I guess I’ll dignify with some acknowledgement. One is Guy Kibbee, Ruth Donnelly, Hugh Herbert and Louise Fazenda as a pair of old married couples who are at the club to get sauced and try and pick up some romantic company of the opposite sex under their partner’s noses. All four of these actors have their usual schtick and are utterly disposable in the movie; cut their part and you would miss maybe one or two good jokes. Which are the only good jokes in the picture, but still.

The other B-story is Robert Barrat in the Lionel Barrymore part of the picture, as an old aristocrat who loses big on the stock market and is determined to blow his last wad of cash at the Wonder Bar. Al at one point even catches him almost sawing into his arteries up at the bar, but I suppose that could have upstaged Jolson for a second and we can’t have that.

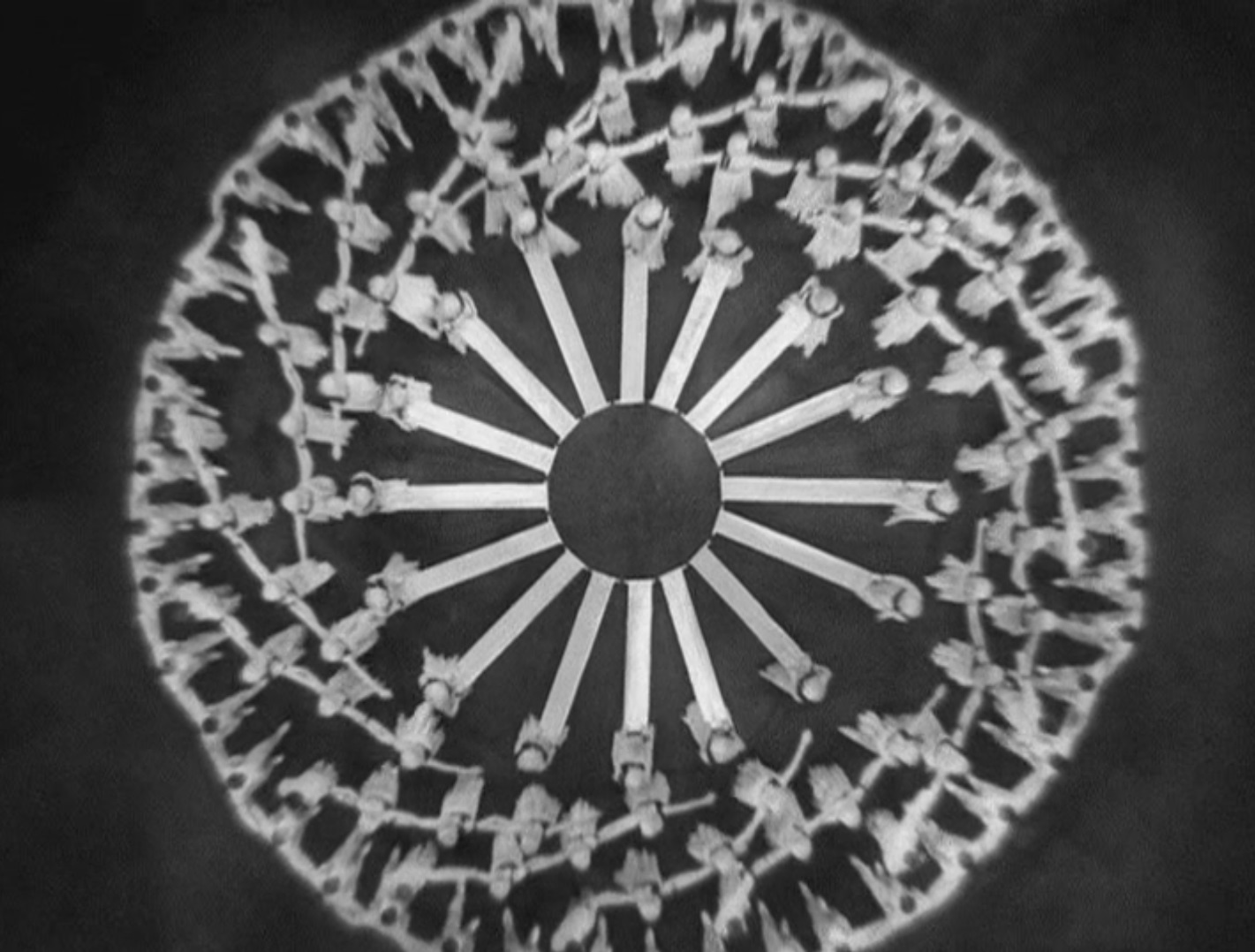

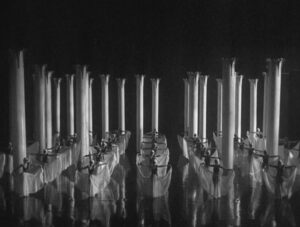

The film is buttressed by several musical numbers crafted by Busby Berkeley. The first is Dick Powell crooning “Don’t Say Goodnight”, which features dozens of blonde dancers sashaying between pillars before moving into the geometric realm and ending in a leaf-strewn forest. Even though the number is ostensibly set during a dance between Harry and Inez, they disappear quickly from the scene and we’re left with Berkeley window dressing, It does a lot of what he’s already done and relies on a lot on very noticeable mirrors to convey depth and expand the canvas. Despite the artistry, it’s interminable, which is about the worst thing a musical number can be outside of outright offensive. (more on that soon)

The next notable number is a dance between Del Rio and Cortez, this time with both of them sticking around for the proceedings. “Tango del Gaucho” (this is what it’s called in the trailer; I’ve seen a few other names floating about) features Cortez whipping Del Rio and flinging her around the dance floor with a disinterested sneer. There is a certain affectation of S&M here, with the violence of their relationship boiling over into erotic frustration. This scene at least mimics the tension present between the two characters and ends with a tense dramatic beat, though I’m not sure the tension is built up to any satisfaction.

But, most notably, Wonder Bar ends with a lengthy blackface number, perhaps the blackface number to end them all. (God, I wish.) Al Jolson, most famous for his jazz hands, his mammy, and his The Jazz Singer heralding the beginning of the talkie era of film, can’t resist the pull of burnt cork and blacks up for a number called, “Going to Heaven on a Mule.”

The set piece, which stretches for an agonizing 10 minutes of screen time in this 84-minute film, features him as a poor dirt farmer singing to his relation (a little girl, also in blackface) about his idea of what heaven must be like. And then we’re treated to Jolson with a pair of wings on top of a mule (also possessing a pair of wings) crossing the rainbow bridge to the afterlife. Here he’s presented with everything a poor black man could supposedly want, at least to the limits of the white imagination. He also dances with others in blackface, including the Gabriel, St. Peter, three little boys dressed to be cherubs, the Emperor Jones (!), and Uncle Tom, which… I mean…

These undeniable desires includes vagaries such as pork chops hanging from trees, all the cooked chicken you could eat, craps games where you always roll sevens, and free watermelons at every turn. Even before we take into account Jolson’s mugging, the movie is revolting in the way in pulls together these racist tropes. That’s only compounded by Jolson’s wide-eyed, wistful excitement; this isn’t done from a place of mockery, but of gleeful celebration, and undoubtedly a mountain of ignorance that one would imagine stands tall above Everest.

In terms of unpacking Jolson’s own relations with blackface, I will defer to Erich Kuersten at Acidemic, who goes into depth and detail about how why Jolson was drawn to blackface. (Don’t ask me about his Dolores Del Rio opinions, though, that is just beyond me.)

In his book Dangerous Men, Mick LaSalle describes Jolson as the troll king of early sound film, the golem who segued between the lovesick circus freaks of Lon Chaney-Tod Browning silents and the fast-talking toughs of the pre-code gangster boom. Jolson’s inner deformity was a sense of insecurity and self-loathing so intense it became its own grandstanding narcissistic opposite. A kind of slow motion downward death spiral down a Vitaphone crackle-and-hiss drain, it was if being the first person to speak and sing on film had left him permanently self-conscious, yet tickled to a childlike fit of jouissance over the attention it got him: “In film after film, Jolson not only watches himself, he watches you watch him,” notes LaSalle. He’s a “borscht belt Pagliachi… a monster as masochistic as Chaney, but needier, more self-pitying, and, of course, louder.” (18-19)

Now there are some who think two wrongs don’t make a right, but this ground zero of semitic self-loathing coupled to black-face racism has a train-wreck pull for others, such as myself. Does it help that Jolson was a big supporter of black entertainers and possibly felt a kinship with oppressed African Americans? A Jew who played up his own Jewishness, Jolson had to struggle with stereotypes himself in an age where clubs were openly ‘restricted’ and long before Gregory Peck made his Gentlemen’s Agreement. Jews and blacks alike had to play humble, decent, and naive to avoid racist ire. […]

More than anything now, in today’s light, minstrelry is our shame, not Jolson’s or anyone else’s. It’s a sad example of the white compulsion to smite or mock all difference, a need still prevalent underneath the skin of so much news channel rhetoric. And yet, at the same time… exaggeration and performed accentuation of difference is sometimes the gateway to tolerance.

On one hand, I admire Erich’s willingness to investigate; it is very easy for me to point to the sign saying “minstrelsy BAD” and pack up for an early dinner. Jolson did think what he was doing was a sympathetic homage; case in point: his blackfaced singer in Wonder Bar popping open a Jewish newspaper with a smile on his face. (And, no, I have found no satisfactory explanation for this moment; again, the past is a mystery, enjoy not knowing things.) And Jolson wasn’t alone in this, much in the same way Astaire’s “Bojangles of Harlem” number in Swing Time was meant as a tribute to Bill Robinson and the many dancing legends he admired.

But these same tributes and any appreciation for them have to also leave a very stark piece from the picture, the systemic racism in place in Hollywood at the time. I don’t know Erich personally, but from reading and admiring his work for years, I do think he has a more generous belief in human kindness than I do. (I also believe this assertion would make him laugh, but I am one hell of a pessimist.) Saying “exaggeration and performed accentuation of difference is sometimes the gateway to tolerance” is fine if you’re the one doing the exaggeration and accentuation, not so much if you’re the ones being dehumanized and exploited.

A number of reviews I read have pondered wearily about the reaction to this number, about why it was made and who wanted to see something like this. Was this something people knew was wrong or misbegotten? From my reading, it’s deeply unlikely that the mostly-white audience would see anything out of the ordinary with it; minstrelsy had been an American staple for over a century by this point. However, it is notable that this number wasn’t screened for the Studio Relations Committee. As noted in Vieira’s Sin in Soft Focus, producer Hal Wallis, not wanting to get them worked up, simply told them the number was unfinished and “there was nothing to worry about”. Of course, upon seeing the completed movie, the SRC focused it’s main energy on the controversial “boys will be boys” line, but the fact that “Going to Heaven on a Mule” wasn’t screened for them is a telling moment.

For people who still have a shred of doubt, here is the film’s trailer building up the number, of which it only features a still of Jolson on the mule:

“Going to Heaven on a Mule” is a musical creation so startlingly different that to show you ONE SINGLE FLASH of its 42 unforgettable scenes would rob you of the greatest thrill you’ve ever had in a theatre

“Thrill” is certainly one way to put it. The foreignness of the past, the intangible relating to how other people through history lived, thought, and felt, is explicitly felt throughout “Going to Heaven on a Mule”. No doubt as we age– and I know you, the reader, are somewhere on this spectrum as well– things become comprehensible to us but no one else. Life moves so fast; I’m still pissed off about the Iraq War. I’m not even sure if modern history books even cover it.

The setup and structure of Wonder Bar feels very much like 42nd Street and Grand Hotel jackknifed into each other at full speed, leaving a wreckage-strewn scene coated in blood; now Al Jolson has popped up and started tap dancing on some loose brain matter. (I might be more generous if the film Night World from 2 years earlier didn’t just have a Berkeley number but had an actual plotline for an actual black actor and not a 10-minute-long blackface number that harps on every single racist stereotype about black people in existence. Night and fucking day.)

Kay Francis’ entire role is 85% sitting at a table looking miserable before rounding it out with a brief sojourn to sitting in a car and looking miserable; she is horribly misused, making this a case in point in just how much Warners used and abused its stars who didn’t stand up for themselves. Del Rio fares only slightly better as she’s put in a few fetching gown and one stunning negligee earlier in the film and is at least given the semblance of a character arc, even if it is such turgid dead weight that not even Olivier could have pulled it off. Dick Powell is wasted here, in a role well below him at this point, and I think I’ve sputtered everything I needed to about Jolson; don’t get me started again.

Pretty much the only joy to be had from the film is betting on who is going to murder Ricardo Cortez in this one and how. (Kay Francis already had a notch on her belt in the Ricardo murder department from House on 56th Street, so it was hard not to pick a favorite.)

As you’ll see in the links below, I’ve read probably more than a dozen different pieces about Wonder Bar, a handful from modern sources that are even favorable towards the picture, and all of them try desperately to draw out some deeper sense of moral purpose from the movie. A lot comes from the film’s finale, which is worth remarking on as a notably pre-Code moment, one that is heartless and callow enough that I actually gasped.

Spoilers.

Del Rio, during the aforementioned S&M dance number with Cortez, stabs him in the chest, fatally wounding him. The way it goes down, the only people who know that he has expired are Al Wonder and his maître d’ (Henry O’Neill). Al, who has been listening all night to his friend the baron laying out his suicide plans, then sneaks the corpse into the back of his friend’s car, losing a pal but covering up the murder of the woman he loves at the same time.

It’s bleak, Al being not only okay with covering up a murder but essentially not stopping a suicidal friend all in the pursuit of Inez’s love and safety. And of course Al doesn’t end up with Inez– he’s the sad clown, remember?– and must live with this, though he doesn’t seem especially bothered. Al Wonder is Al Jolson, after all, and as long as the camera is on him, nothing else really matters all that much.

End Spoilers.

Wonder Bar is a nightmarish mess of a movie, one I found deeply unpleasant, like looking too far into the cracks of history and finding a pulsating colony of hungry spiders staring back. It has no heart, no soul, a wild swing at sophistication that belies a core emptiness, a desire to take all that is poor and ragged about the human condition and make it about themselves. The star-studded cast looks lost and confused, while Jolson slides in front of them at the drop of a hat to put on a soft shoe.

All of this is done in sort of a collapsed cellar of the usual Warner Bros. big musical flare, making it feel like more of a miracle how spectacular and fun movies like Footlight Parade and Gold Diggers of 1933 were. For serious students of cinema and how race was shown on screen and how pre-Code Hollywood flew off the rails in 1934, this is probably a must-see. But is that you? Probably not.

Go get some sleep. I don’t care what time it is. Your body will thank you later.

Screen Capture Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- The film’s AFI notes reveal that Warner Bros. had quite a fight to keep the “boys will be boys” joke in, and that, surprisingly, the film was approved for reissue in 1936 without the cuts even after the Production Code was more strictly enforced.

- I don’t suppose you want to know this, but the film was a massive hit at the box office in the Depression tinted year of 1934, bringing in three times its budget.

- Senses of Cinema talks about some behind-the-scenes stuff, including this revealing information of what the Studio Relations Committee was shown of

Unlike its [pre-Code Busby Berkeley musical] predecessors, however, Wonder Bar‘s European setting freed the studio from their previous musicals’ immersion in the New York proletarian and showbiz milieu, enabling the filmmakers license to depict the amoral high life of Parisian nightlife. The film’s amorality challenged the official overseers of content at the Studio Relations Committee, recently headed by Joseph Ignatius Breen (to be renamed the Production Code Administration in mid-1934). By simply not responding to the Committee’s objections, studio head Jack Warner unleashed Wonder Bar on the market in the spring of 1934. Even in script stage, the SRC objected in particular to the “irregular sex relationship” between Harry (Ricardo Cortez) and Ynez (Dolores del Rio), discerning in it strong intimations of sadomasochism, which became overt on screen. As Mark Vieira also relates, the musical number “Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule” was not even shown to the SRC, since executive producer Hal Wallis assured the Committee that “there was nothing to worry about” in this and another musical interlude.

- Here’s an excerpt from Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley by Jeffrey Spivak that details how the “Don’t Say Goodnight” number was crafted:

Buzz asked Warner Brothers’ property department head Albert Whitey for twelve mirrors, each of which was to be twenty feet high and sixteen feet wide. The mirrors were placed on revolving floors in an octagonal arrangement. The columns slide in and out as masked male dancers join the girls. So brilliant is the conception that one scarcely realizes which dancers are mirror images. At the apex of the number, one black curtain is raised to reveal more reflections, followed by a second curtain and a third revealing the manufactured image of thousands of dancers, all caught with an incognito camera that, by all the laws of reflective physics, should be seen in the octagonal mirrors. This kind of visual spectacle is one of Buzz’s very best, heartbreakingly beautiful in its technique. When the magician reveals his secret, the effect is no less impressive. “The cameraman and the front office thought I was crazy because they thought the camera would show in the mirrors, but I tricked it so it would never show,” explained Buzz. With a miniature set of mirrors in his office, Buzz experimented with a pencil that had a small strip of white tape on it. He moved the pencil around to the point where he could look at the tiny mirrors and not see the white tape. The camera would act like the white tape. Buzz had it placed on a piece of pipe (the pipe acting as the pencil). Where the mirrors butted together stood a narrow white column. If the camera was placed in just the right position facing the column, its reflection wouldn’t be seen. But what about the camera operator? Per Buzz: “We finally had to dig a hole through the stage floor and we put the camera on the piece of pipe. The operator laid flat on his stomach underneath the stage and crawled and moved around slowly with the turning of the camera.” It’s a splendid, awe-inspiring effect whose power and trickery isn’t diminished even after multiple viewings.

- Over at KayFrancisFilms.com, they talk about how the film was sold on a bait-and-switch. Kay was the headliner on the posters and advertisements for the movie, but Jolson was the film’s real lead. In fact, Francis wasn’t originally slated to take the role; it was originally set for Genevieve Tobin. Here’s Kay’s thoughts on the film:

“Frankly, I did not want to take part in that picture. I made no secret of my dissatisfaction with my role. It was a small, inconsequential part, and I believe (and I still believe) that I should not have been forced, by my contract, to play it.”

- Jay Car at TCMDB talks mostly about Jolson and his persona, adding that Wonder Bar is “benchmark in the history of what Hollywood thought was OK to put on screen in 1934, before the withering hand of the Production Code descended like a shroud over the movies.” He adds some background info for the “Mule” number:

Even if we allow that it was in part a parody of Marc Connelly’s The Green Pastures, a pseudo-folk rendering of an African-American heaven that won a Pulitzer in 1930, but today is virtually unwatchable, Going to Heaven on a Mule is cringe-makingly appalling in its racial stereotyping. (Its insensitivity is signaled earlier in a brief but offensive exchange between Jolson and an Asian checkroom worker.) Not even a glancing reference to Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones can disguise it from the fact that it’s a blackface routine, with Jolson as a dying field hand in overalls and worn work shirt, departing his decrepit shack for an art deco afterlife.

Most of the singing and dancing there takes place at the intersection of The Milky Way and Lenox Avenue as if heaven’s newest resident would have heard of either. He’s accompanied in a safely sexless way (we hope!) by his beloved mule. Pansy angels fit him out with wings as Bill Bojangles Robinson appears as a tap-dancing angel in black tights, white spats, a shiny top hat and wings of his own. Whew!

- Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times notes of the movie, “It is scarcely fair to make comparisons between this production and other musical pictures” though he emphatically leaves out whether that is a good or a bad thing. As for the lengthy blackface number, he notes his delight and fascination with it.

Busby Berkeley gives several striking dance groupings and besides this angle of the film there is a series of settings that serve as the background for Mr. Jolson’s song, “Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule,” which is rendered by the popular entertainer in black-face. There is a conception of Heaven, with a black St. Peter, a black Archangel Gabriel and black angels. There are several amusing features to this section of the film, including the idea of having a “Chute to Hell,” a board on which is registered the number of persons in the Celestial regions and in Hades, and wings on both Mr. Jolson and his mule. Heaven, as viewed from the outside, is a jumble of modernistic structures leaning in all directions, with a tremendously high and exceptionally narrow entrance.

- Variety is up on the film, saying it will do well in foreign markets, noting at the end, “It’s Jolson’s comeback picture in every respect. With 10% of the gross due him, he’s in for some fancy gravy besides.”

- Glenn Kenny at Some Came Running confesses to his own obsession with Jolson. What fascinated me with this piece is how it goes into Jolson’s legacy. The laserdisc collection of his films from the 90s featured him in full blackface, whereas the DVD release of The Jazz Singer went with a tasteful outline. He also relates the story of a childhood friend who would do a Jolson impersonation in blackface in the 1970s on stage and even television, starkly noting “There was hardly a raised eyebrow.”

- The Toronto Film Society‘s piece includes a quote from professor and author William K. Everson’s film notes from when he showed the movie to a film society in December 1964:

The final number, “I’m Going to Heaven on a Mule”, is something of a revelation. When Wonder Bar played at the New Yorker on a single-day booking, a few years back, the complaints in their guest book were quite vehement from those who felt it was a kind of paean to Uncle Tom racism. Actually, the poor innocents were not even aware that the New Yorker print was a working TV print in which the whole middle section of the number, with the most blatant stereotypes, had been bodily removed. This print has the number intact, and it gets more and more astounding as it progresses! Physically, this is one number that couldn’t be staged in a night-club, and ethically and intellectually, it’s a number that probably wouldn’t be staged anywhere. Here at the Huff, we’re so inured to minority-group comedy and stereotypes in films of the ’20s and ’30s that it is certainly not going to produce any reactions of shock and indignation, but I daresay it’ll cause a little surprise. If the pressure-groups were so inclined (and if they knew their facts and film history a lot better than they do!), this little hot potato could well be made the standard-bearer for a whole new crusade, which at least would have the salutary effect of taking some of the ill-deserved heat off The Birth of a Nation!

- Here’s the film’s trailer:

Awards, Accolades & Availability

More Pre-Code to Explore

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 Comments

arlissarchives · April 16, 2021 at 7:31 am

When the reviewer begins by declaring “I hate Al Jolson,” I know I’m not going to read a balanced evaluation. Perhaps it would have been better to say that Jolson is an acquired taste and those that have it really like the guy, outsized ego and all, and those who don’t will never understand the attraction. Ironically, the typical criticism against WONDER BAR is summed up as “Never has there been so little of Al Jolson in a Jolson movie.” The most objectionable part is of course the “Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule” sequence that was created by Busby Berkeley. Why blame Jolson? Its jaw-dropping bigotry may have triggered the beginning of the end of such numbers in films. Two years later when Fred Astaire did a blackface tribute to Bill “Bogangles” Robinson in SWING TIME, it was regarded as a sincere tribute. Today reviewers don’t quite know what to make of it – it deserves our condemnation but dammit it’s awfully well done. Such a quandry.

WONDER BAR was based on a1931 stage play that lasted 81 performances on Broadway. But Jolson took it on tour where it apparently enjoyed much success. The play even had a hit song, “Oh Donna Clara.” The stage songs were dropped from the film and all new songs were written by Dubin and Warren. The all-star cast was Warners’ guarantee against a flop since Jolson last few films had done poorly. Despite his limited screen time and being thrown in with very popular film stars of the day, Jolson managed to walk away with the film in the eyes of most people. Jack Warner was sufficiently impressed to offer Jolson a new three-film contract and, reportedly, the film was Warners biggest hit of that year. Strange, bizarre, and somewhat deranged, WONDER BAR is one of a kind..

Jan S Ostrom · April 16, 2021 at 7:32 am

This is absolutely excellent, thank you. I (white) saw this in my first film class and was so turned off, I was queasy. Never got the appeal of Jolson and was told “you had to be there, he was electric.” I screened small discrete parts in later classes as a teacher, but with warnings and context, because I couldn’t ignore it in the timeline. Many young students referred to it as a cartoon… but only the white ones. The black kids were quiet. This was years ago and I wish I had done a better job back then. Thank you for ALL your great writings!

Dave Campbell · April 16, 2021 at 8:24 am

One positive aspect of your viewing of Wonder Bar is that the loathsome elements of the film–and there are more than one or two–inspired some of your most incisive and detailed criticism producing a good deal of in-depth commentary on this weird and unsettling musical. At the end of Del Rio’s “Don’t Say Goodnight: number, she mutters “why can’t this go on forever?” and I suspect Danny could give her at least a dozen reasons. My favorite scene in the nightclub pictures Kay Francis, bored to tears, flicking a cigarette ash backwards over her shoulder: simple gesture, but certainly expressing her bored contempt for all the luxurious silliness around her.

James R Long · April 16, 2021 at 10:03 am

Danny,

For a film that you disliked, you sure spent a lot of time and effort on this one!

The sad thing is that this film probably comes as close to capturing the mystique of Jolson as he was on stage than any of his other movies.

Thanks for the links to the other information.

Jim

Kurt McGill · April 16, 2021 at 3:08 pm

Amazing blog. Website. Exotic! Non plus ultra. Ricardo Cortez (future stockbroker – Jacob Krantz from Manhattan?) Such an underrated actor. A Jew doing an impersonation of Rudolph Valentino. (They needed a Valentino.) I’ll leave the woke revisionist-history to my betters…

Tom Samuels · April 20, 2021 at 5:55 pm

I appreciate the work you put into the review, but couldn’t you have left out these two paragraphs?

“Let’s start with this: I hate Al Jolson. He is a ham, he sucks up all the oxygen in the room, he’s the star attraction who knows he’s the star. He is always at ’11’ on the dial. He makes stars like Mae West and Eddie Cantor look demure. I don’t like his singing. I don’t like his acting. And, frankly, I don’t like the person I become when I watch his films.

(Don’t let that make you think I don’t think he deserves my ire. Though perhaps I consider him beneath it.)”

I don’t understand the point you’re trying to make, and, to be honest with you, it’s more fitting of a diary entry than a film review. Again, I appreciate your work, and I hope you keep at it.

Thank you,

Tom Samuels

Danny · April 22, 2021 at 11:13 pm

I have it in there as a point of honesty; why dance around it? If you get to this part of the review and go, hey, I like Al Jolson, then you will know whether or not to take what I’m saying with a grain of salt. Even if you don’t know Jolson at all, I assume you’ll at least be intrigued by my description. All of the reviews on this blog are deeply subjective– hence the rating system. And I do write very regimented for many of my reviews (yay journalism undergrad), but every once in a while I think it’s important to shake things up, especially for a movie that so often defies description and belief. Thank you for your comment.

Margaret Thomas · April 20, 2021 at 6:06 pm

Everybody is entitled to their opinion, so I will give mine. You simply are dead set frightened of contemporary society not accepting you! yes there is flaws with Wonderbar and Al Jolson himself, but the way you are expressing this is an out and out plea to the world” Hey world don’t think for one second I like this old stuff, particularly when the King of Old AL JOLSON IS THE STAR!

Jean · April 20, 2021 at 7:46 pm

The truly remarkable thing about this movie is that we are left approving when someone gets away with murder- surely the various censors (Hays, studios, government or whatever) in Hollywood have rarely allowed that sort of thing.

Comments are closed.