MGM: The Dream Factory

The story of the rise and fall of Metro-Goldywn-Mayer reads a lot like a Hollywood movie. Behind the scenes are filled with turmoil, tragic deaths, illicit affairs, and, in front of the cameras, the most glamorous, popular movies in the land.

Louis B. Mayer.

Formed by a merger between Metro Pictures, Goldywn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures under the aegis of Marcus Loews’ movie theater company in 1924, MGM quickly ascended to the top of heap of major motion picture studios with silent epics like Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ and The Big Parade. From its inception to the 1950s, MGM was the most popular of the major studios and famous for its huge stable of stars.

Two personalities helped shape MGM in the pre-Code era. The first is studio head Louis B. Mayer. From buying and renovating an old burlesque house and turning it into a theater to owning a chain that comprised most of the movie houses in the Northeast, Mayer’s tenacity was unmatched. He began producing his own pictures in the late 1910s, and by the early 20s merged his studio to create MGM. He stayed on as the studio head. Called everything from intimidating to a total ham, Mayer’s 27 years at MGM were best represented by films like The Wizard of Oz (1939) to the lengthy Andy Hardy series.

The second personality is Irving Thalberg. A relatively young man for being head of production at the giant studio (he was around 30 when the pre-Code era began), Thalberg’s role in charge of the productions at MGM meant that practically every film crafted at the studio took significant input from him in terms of material chosen and story decisions. Often called “The Boy Wonder”, he often figured out the best ways to adapt stars for their material and vice versa. Preferring more literary works than Mayer’s ‘crowd pleaser’ stable, the two developed a contentious relationship. Though he would butt heads with Mayer, his ability to craft eloquent, epic yet accessible dramas makes him one of the defining forces of not just pre-Code, but of all of Hollywood film making.

Norma Shearer and Irving Thalberg.

No studio in Hollywood had as deep of a roster as MGM, a studio which proclaimed to have “more stars than there are in the heavens.” MGM took great care to transition its silent assets to sound, giving Garbo months of prep time and carefully grooming their talents to eliminate any rough patches.

The studios biggest stars included Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, and Joan Crawford, all making their transitions to the sound era. On the male half of the equation, MGM had wisely scored a coup in hiring both John and Lionel Barrymore, two of the most respected actors of their time (though John, undoubtedly, was beginning his decline into alcoholism). Signing a young Clark Gable was a major coup for the studio after Warners passed on a contract for him in the early 30s, and he soon worked with many of the most famous actresses on the lot.

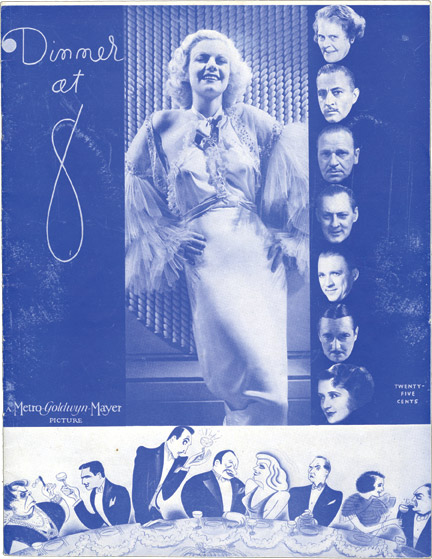

The cover of Dinner at Eight‘s publicity book.

The glamor of MGM in the pre-Code era could be said to culminate in 1933’s Dinner at Eight, a star-studded affair similar to the previous year’s Best Picture winner Grand Hotel but with even more star wattage inserted. The film, based on a hit Broadway play about a the lead-up to an oddly attended dinner party, shows off the studio’s ability to meld comedy, drama, and its verbose but pompous style.

MGM had never made films that knotted up censors like Warner Brothers and Paramount with one notable exception: 1932’s Red Headed Woman, a concentrated attempt to outdo the other studios at their own game while emphasizing Jean Harlow’s Hell’s Angels image as a blonde bombshell. The movie, which features a spectacular amount of adultery, a scene in which the romantic lead beats Harlow and she begs for more, and even a sly shot of Harlow’s exposed breast, was a scandalous box office success. However, the ensuing controversy, including the film being outright banned in Great Britain, is often cited as one the major turns toward mandatory Production Code enforcement after 1934.

MGM was one of the only studios to turn a consistent profit even during The Great Depression and remained the biggest studio in the world until the mid-1950s. Mayer’s death in 1957 (Thalberg had passed in 1937) came after he lost control of his studio, where their mandate of colorful, lavish musicals was more of a costly liability than a guarenteed hit machine. The 1960s would see the studio increasingly rely on the blockbuster formula of making a great deal of money on tentpole releases like the remake of Ben-Hur (1959) and using that to offset the studio costs. Major flops, however, derailed this, and within a decade MGM had whittled down to next-to-nothing.

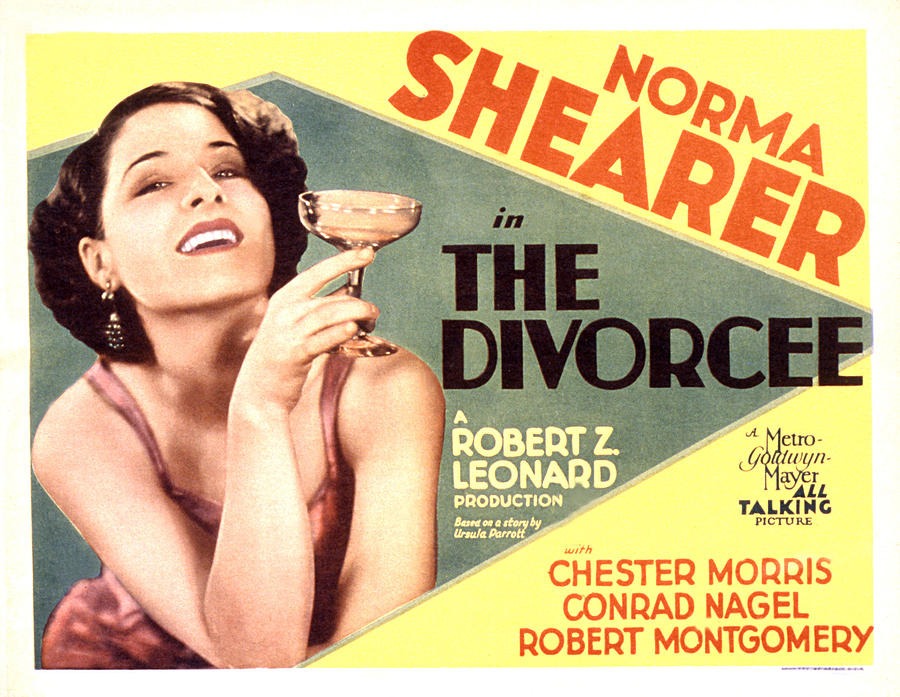

Poster for The Divorcee (1930).

After being bought and exploited as a front for a series of hotels and casinos, the studio became more of a boutique label that to this day co-produces a dozen or so pictures a year. From Ben Hur (1925) to co-producing Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters (2014), it’s certainly been a long, crazy road.

Defining Films of the Era

- The Divorcee (1930) – Best Picture nominee, won Norma Shearer a Best Actress Oscar.

- Anna Christie (1930) – Greta Garbo’s first talking picture.

- The Big House (1930) – Drama set in prison that earned a Best Picture nomination.

- Trader Horn (1931) – African safari film that earned a Best Picture nomination.

- The Champ (1931) – Best Picture nominee.

- Grand Hotel (1932) – Best Picture winner of 1932.

- Smilin’ Through (1932) – Best Picture nominee.

- Red Headed Woman (1932) – One of Jean Harlow’s most famous roles, and is among the films counted as causing the Code crackdown of 1934.

- Dinner at Eight (1933) – MGM’s follow-up to Grand Hotel with many of the same stars.

- Viva Villa! (1934) – Best Picture nominee and the highest grossing film of 1934.

- The Thin Man (1934) – Best Picture nominee. Began the long running series of detective movies starring William Powell and Myrna Loy.

Notes and Availability

- All pre-1986 MGM movies are owned by Warner Brothers, who releases them through their Warner Home Video and Warner Archive labels.

|

|

|

|

|

| Fox | MGM | Paramount | RKO | Warners |

|

|

|

||

| Columbia | Universal | United Artists | ||

| Studios Main Page | Home Page | ||||