|

|

|

| Marie / X-27 Marlene Dietrich |

Colonel Kranau Victor McLaglen |

Chief Gustav von Seyffertitz |

| Released by Paramount Directed by Josef von Sternberg Run time: 91 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- The opening shot is of Marlene Dietrich adjusting her stockings. It’s called an attention-getter.

- The opening also involves a prostitute having killed herself by sticking her head in the oven, revealing our own heroine’s death wish.

- A woman requests to die in the uniform she wore serving her countrymen, rather than the one she wore for her country.

Dishonored: Standing Up for Love

“I’m not afraid of life. … Though, I’m not afraid of death, either.”

The opening of Dishonored features a war widow glumly watching a suicide victim being pulled out of her house. She gets that feeling. I get it too.

The widow is Marie (Dietrich), so we know she’s going to go on to greater– well, other things at least. Noticing her disaffected attitude with life and her alluring looks, the head of the Austrian spy league recruits him to their side in the country’s ongoing war with Russia.

Marie slides into the role ably and into the new glamorous gowns she wears unsurprisingly. With a bit of wit, she’s able to immediately uncover a mole and weasel out Kranau (McLaglen), a Russian spy.

The film quickly becomes a con game between the two, both excited by the depths of one another’s treachery. The shell game involves a certain amount of allure as the game becomes less about national loyalty but the upper hand. He finds her chameleon-like abilities and embrace of death highly erotic, and he… he entertains her a bit.

Things reach a boiling climax after she drugs him and smuggles out the Russian war plans via a song that she composed. He’s captured and gives her a rueful smile. She secrets him away to another room and pulls a gun. The sound of the nearby airport are driving him crazy.

Plot descriptions for von Sternberg films seem arbitrary. They’re better reviewed and illuminated as a sort of mood– seedy, dark, haunting. von Sternberg uses Dietrich’s finely etched face as a screen on which to project the ugliness and loneliness of the world. She remains icy cool throughout, only throwing it off for the occasional disguise.

Spoilers.

The film is fine throughout, but the film’s ending is– and I don’t say this lightly– amazing. Marie is put in front of the firing squad for letting Kranau escape. She opts for the clothes she wore as a streetwalker, unsentimental and plain. As she stands before the squadron, the young officer leading the instructions (“Ready… aim…”) doesn’t finish, having a complete breakdown over having to execute a woman.

This character, who we hadn’t encountered up to this point, pleads for Marie’s life, begs for her. In a more romantic film, this would have been the climax, as Marie is saved by the kind love of a enamored romantic. Or maybe McLaglen will parachute in and save the day. God may even appear in a zeppelin and whisk her off at least to Hungary.

But Marie knows the score as well as the scuffling officers, taking the opportunity that her paramour affords her to fix her hat and adjust her stockings. It’s such a beautiful moment, one that knows the character, running the film parallel to the woman’s suicide earlier in the movie. They’re both killing themselves, but Marie died for something greater than country and for more than just her selfishness.

End spoilers.

Dishonored is another fine collaboration between Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg. Comparisons will abound to then-rival Greta Garbo’s similar Mata Hari, but the two remain an interesting contrast in styles. Both are stylish women’s pictures about choosing love over life and country. The MGM film succeeds with dialogue and temptation– it’s a richer story about emotion and sacrifice. By contrast, Dietrich’s allows the audience plenty of leeway to find their own emotions, and make their own decisions about the baroque surroundings.

This version is a little tougher to resist simply because it isn’t romantic. McLaglen jets still assuming he’s simply gotten the upper hand, never knowing his salvation came from the dark depths of a woman whose emotional high wire act usually keeps such depths invisible.

Of course the dialogue could use some polish, and of the many statuesque close-ups of Dietrich’s face, a few do leave you wondering if the actress may not have needed a few more moments of character to sink into. And Victor McLaglen’s Kranau needed something else to make his character more alluring. Or the least just a little alluring.

But those aspects subtract from the film’s tone, one where we’re led to an atmosphere rather than a story. Sternberg would perfect this sort of mythical storytelling with Blonde Venus, and Dietrich would get all of the depth and power she could manage with Shanghai Express. It’s interesting to see the evolution in their collaborations, and, in my opinion, none of them are disposable.

Screen Capture Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- Genevieve McGillicuddy at TCMDB calls the film, “a fascinating portrayal of sex and death”, noting about its production:

Initially, Gary Cooper was to re-team with Dietrich, but the role eventually went to Victor McLaglen.

Cooper turned down the part not because of any friction with his co-star, with whom he was having an affair, but because of his unwillingness to work again with director Josef von Sternberg. Now working on his third film with his muse, von Sternberg wished to expand the gallery of Dietrich characters. In Dishonored, Dietrich takes on a variety of disguises – at one point, shedding makeup and the usual glamorous wardrobe to don a peasant girl outfit.

- Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times calls this “highly satisfactory”, noting:

Miss Dietrich’s performance is intelligent and beguiling. Victor McLaglen does moderately well in most of his scenes.

- History on Film connects this to the real life case of Mata Hari (not by a whole lot, really), but still enjoys the film.

Director Josef Von Stemberg was far more interested in playing with shadows and portraying Dietrich as an object of male worship than historical accuracy, or any discussion of the war, other than as a backdrop where Dietrich could parade herself. Austria did experience a number of humiliating defeats in the first two years of the war, but they were caused by mind-boggling incompetence, not espionage.

- Erich Kuersten at Acidemic really has some fun comparing this to Song of Songs (1933). These snippets do contain spoilers:

For [von Sternberg], if there is actual love it’s always a renouncement, a sacrifice, done more for the dramatic spectacle of masochistic suffering than the actual object of affection. […] Her grand gestures are like suicidal whims made extra potent by the sheer folly of them, their undeserving target making our masochistic frustration as spectators boil over, which is their whole performative point (“happily ever after” in a Sternberg-Dietrich film would be an oxymoron) […]

She knows her masks are all there is and through acting she devours the firing squad with the ambivalent curiosity of a cat playing with a box of regimented mice. Dietrich in the JVS movies knows she has only 90 minutes in which to exist so she may as well go out impaled-butterfly-pin high than preserve herself in some uncertain happy ever-after of old age make-up and bucolic leaf-eating caterpillar drudgery.

- Pare Lorentz’s contemporary review refers to Dietrich as “(Legs)” and disparages the dialogue, though he enjoyed the film overall.

Starting with this complete outline, the dialogue writers used East Lynne as a model of dramaturgy and actually put on paper words that even in these talkie days seldom have been seriously employed as dramatic sentences. Yet, notwithstanding this almost completely idiotic handicap, Dishonored is pretty exciting.

- Plenty of blu-ray screenshots over at DVD Beaver.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

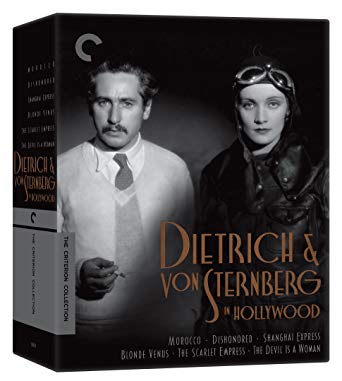

- Available in a two-pack along with Shanghai Express thanks to TCM. It is also part of the Criterion von Sternberg/Dietrich set which you can get on DVD or blu-ray.

More Pre-Code to Explore

1 Comment

thestoryenthusiast · April 29, 2019 at 10:00 am

“von Sternberg uses Dietrich’s finely etched face as a screen on which to project the ugliness and loneliness of the world.” Perhaps the most perfect summation of their collaboration I’ve ever read.

Comments are closed.