Proof That It’s Pre-Code

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Blood, guts, naked butts and gore, all in hefty doses considering the period it was made in.

- Our soldiers get a brief reprieve to make love, which includes some unmistakeable gasps and coos.

- Considering its anti-nationalistic bent, it would never have been made five years later.

- One soldier craps his pants, someone says “shove it up your ass” in French, and we even get a guy kissing another on the mouth in the barracks. Let’s see you do that, Saving Private Ryan.

- Here are a few examples (click for big):

All Quiet on the Western Front: Destruction of Innocence

“We live in the trenches out there. We fight. We try not to be killed, but sometimes we are. That’s all.”

All Quiet on the Western Front remains one of the most famous Pre-Code films, a war epic Best Picture winner whose echoes reverberates through every war movie made afterward. So when I call the movie ‘iconic’, that still may be underselling it.

Based on a bestselling 1929 novel, All Quiet centers on the lives of a schoolroom of German boys who will soon understand the ugly truth of war. The deafening cries of the crowd as soldiers march off to the front almost drowns out the discussion in a classroom– what cleverly appears at first to be patriotic fervor drowning out all reason– only to find that the place of reason, too, has been turned into a pulpit for politics.

The bespectacled professor implores his young students to head to the front, for glory and honor. We watch as they daydream their way into parades and women’s hearts, and the excitement overtakes them as well. Most of these young men look vulnerable, but eager, and none embodies this moreso than Paul (Lew Ayres), a writer who can’t help but get caught up in the enormous excitement and equally enormous societal pressures.

When we first find Paul, he’s pensive and contemplative. You can watch throughout the early scenes as he’s swept up in the patriotism like the rest of his class.

We follow the cadets into basic training; they’re prepared for a lark, but find themselves lorded over by a commandant who was once their town’s postman. He has them crawl through mud for his own bemusement, and the cadets see him simply as an obstacle to the jolly business of war. They get their revenge, throwing a sack over his head and spanking him with sticks; a brief reminder that these are still very much kids.

Of course, World War I does not turn out to be a picnic. Arriving at the front, the boys are introduced to a wise commander who instructs them to get used to being hungry. He’s Kat, a blunt little man with a nasty laugh. He’ll do his best to guide these recruits to what the war really is: attrition and bloodshed.

We follow the soldiers as they’re trapped in a bunker for days under fire, as they gallantly run into No Man’s Land, and as they spend their final few moments in the hospital, wailing in agony. The film is episodic, slowly letting these bright young men who thought crawling in the mud was going to be the worst of their experience. The faceless class is picked off, person by person, lost to hunger, disease, or madness.

All of the new recruits cower at the sound of shells while Kat chuckles.

Paul survives, though it’s from grim perseverance and plain stupid luck. During one battle, he finds his old commandant has been thrown in to the fray as well. Paul pulls him aside to mock him, only to see the man perish a few seconds later. In the course of the pitched battle in a church graveyard, he gets trapped in a foxhole with a French soldier. He stabs the solider mercilessly, but, surrounded by both sides, he’s trapped in the pit with the dying man.

Being stuck in this situation shakes him to his foundation. Earlier he’d made fun of his commandant for being afraid of the fight, and this close call proves that his veneer of bravado remains fragile. He watches the French soldier die, slowly, and flips between bouts of anger and appeasement. After a long night, he escapes from the foxhole and breaks down in front of Kat, who tries his best to console him.

A few more incidents occur, including a liaison with a young French woman who seems to have been more interested in the bread Paul brought to the table than the sausage. After an injury, Paul’s sent back home for a brief recuperation, and discovers that the war is still held to a high standard of romanticism.

Paul walks away from his father and his father’s friends, who bicker about the best way to win the war is. They don’t notice him leave.

His father’s friends tell him to fight harder and stop losing, his sick mother tells him to find a less dangerous job, and, the biggest injury of all, he finds his old school professor, still rousing the schoolkids and telling them about the noble heroism of war. When the professor asks Paul to speak a few words about the experience, Paul can barely muster up anything but the cold truth. The professor and schoolboys tear into him, calling him a coward, and he fires back:

“Up at the front you’re alive or you’re dead and that’s all. You can’t fool anybody about that very long. And up there we know we’re lost and done for whether we’re dead or alive. Three years we’ve had of it, four years! And every day a year, and every night a century! And our bodies are earth, and our thoughts are clay, and we sleep and eat with death!”

Paul becomes so impassioned, he decides to end his leave early and head back to the battlefield. There he can at least feel at ease; the war has destroyed his ability to do anything but make war.

Paul is pretty wrecked by the whole war thing. It’s a good thing that doesn’t happen anymore!

Making All Quiet into this movie, a movie from the German perspective, is a stroke of genius. It’s anti-war themes are underlined by the fact that you know from the start that these men are on the losing side of the conflict; still, though they’re foreign, director Milestone takes great pains to make them seem as American as possible so the audience can relate and understand that the sons of all countries are above all still real human sons.

There are no stiff accents here, and besides some references to the Fatherland and the pointy hats, the difference is hardly perceptible. This is all the better to make it a truly universal story. The danger in All Quiet would have been in making it a sly against Germany, which some still interpreted it as; more on that below.

Milestone’s work here is nothing less than phenomenal, and he does a brilliant job recreating Europe on a California back lot. Milestone is cagey enough of a director to be able to switch between an omnipresent camera to the first person perspective. This gives the audience a brief flash of visceral excitement followed immediately by the horrific consequences of such a rush. It’s masterful stuff, and subtle as well.

There’s other tricks I wanted to point out. Milestone has an early scene where the soldiers, trapped in a bunker under fire, find their bread is infested with rats. We watch Kat swing a shovel at the poor mindless and disgusting creatures who were simply seeking out food. Later we see Kat wield the same shovel on the enemy troops as they invade his foxhole, and the connection is clear.

Even rat beating time in the old bunker wasn’t much of a ball.

I have plenty more, and I’ve added some screenshots with discussion down below the main review. Before we get to that, I did want to touch on the film’s ending.

SPOILERS FOLLOW

Believe it or not, Paul doesn’t survive the war, perishing in its final moments in a moment of blissful nostalgia. Spotting a butterfly a few feet away in No Man’s Land, he emerges from the trench to reach for it.

The butterfly is a potent symbol in the movie. As a child, Paul collected and pinned butterflies, an attempt to tame nature and categorize it. Now, after the madness of war, Paul has experienced being the pinned butterfly, and figured it out: nature is beautiful because it is free.

Unfortunately for Paul, this unguarded moment coincides with a French sniper taking aim for one last bounty. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the soldier who takes out Paul looks eerily like the one he stabbed earlier in the movie, demonstrating the circular and unending nature of war in one final, brutal gunshot.

See, Paul? SEE? You’re the butterfly! YOU’RE THE BUTTERFLY

The film’s final epilogue, of shadowy young soldiers marching away from the camera over a field of white crosses, is stunning. The soldiers turn and look back at the audience with sadness and bitterness; this is the same footage from earlier in the movie where the soldiers first make their way towards the battlefield, equating the loss of innocence and war with certain death. This serves as another condemnation, one brilliantly aimed directly at who is responsible for the war.

For while the Kaiser needs his glory, its his people who sing the songs and praises. While the generals are the ones who command the men in battle, it’s we, the audience who allow our sons to go off to war. Few films so nakedly condemn those who have spent the last 150 minutes watching it, and even fewer make it work so poetically.

DONE WITH SPOILERS

Okay, this image may be a spoiler too. But, hey, if you didn’t read the spoilers, maybe they’re marching off to a hot dog stand or something. You don’t know.

The thing that really struck me was how influential the film was not just in its immediate release, but decades upon decades after its release. It’s easy to see parallels and homages throughout modern works like Saving Private Ryan, The Thin Red Line, Jarhead and The Hurt Locker, with the later functioning as almost a beat-by-beat remake in many instances. But every review I’ve read lists a different half dozen war films who have felt the echoes of All Quiet, and each list is completely unique.

There are a number of reviewers complain about the direction or the acting, and in most of those critiques it’s hard not to discount that as movie critics simply grasping at something to criticize; they have to remain relevant somehow. While Ayres is a bit stiff, his transformation throughout the film is nothing short of stunning, and anyone who criticizes this film’s direction is, frankly, nuts.

All Quiet on the Western Front remains a brilliant and timeless story about the foolish things countries do against their own good. Though this movie was made in 1930, the echoes of Vietnam, Iraq and Afganistan now come along with it. We will never be rid of war, but this movie is a vivid reminder of why we must always try.

A Visual Dissection

Early in the film, Paul has the point of his helmet shot off. It 1) metaphorically robs him of his masculine sense of pride, much like war does, and 2) again decreases the gulf between him being a German soldier and just being any soldier.

The movie’s opening is great (and apparently not in the book), as it fully indulges in the early enthusiasm for war. The classroom turns into a wild party as each schoolboy agrees to signup to be soldiers, mirroring the enthusiastic parade outside. It gives the feeling that nowhere is safe from the eagerness to go to war.

There’s a visual motif of doorways and windows throughout the film, with the audience usually peering inside to watch the business of war. It gives the sense that we’re not in there world, but looking in like a voyeur.

Here’s one of the last of the window motifs, as we watch the boys depart their trains. After this, we’ll be on the front lines with them.

As the soldiers disembark from the train, we get a large number of upward shots. Our crew of schoolboys see these soldiers as larger than life, but that will soon change.

If you can’t tell the difference between any of the boys in the back, I think that’s okay. It’s not their personalities that matter, but what the represent. Paul is, of course, front and center, like a real main character.

The movie is filmed in a wider screen than what you’d usually get for the era, and Milestone takes advantage of this, capturing the entirety of the bunker within the frame. This lends to its claustrophobic feel, and the emphasis on the door as the only way to escape it.

As the movie goes along, the towns they pass through become more and more desolate, representing how the fortunes of war aren’t being kind.

There’s a long visual sequence in the movie that’s absolutely masterful, as one pair of comfortable boots are passed from one soldier to another after they die. That Milestone manages to insert this sequence in without killing the narrative flow is amazing, and the way that a short one minute sequence can so quickly explain that the boots are worth more than the array of soldier’s lives is poignant point.

Paul standing over his commandant, leering and gloating.

A few moments later, after an explosion, and Paul’s been thrown under an empty casket. This moment as a living corpse rattles him profoundly.

Paul begs and pleads with the soldier he’s stabbed. This shot looking down on him makes him appear pathetic and small, matching his mad state.

The dead soldier looms over him again. His tranquil face is a stark contrast to the pain Paul will have to continue to endure.

Paul and one of his few surviving friends go to a bar to unwind, and a mirror allows the audience to watch these men watch this poster and fantasize about the woman with the umbrella in a sad attempt to feel something outside of the conflict.

Back in his hometown, Paul sees this, which pretty much says everything.

Paul stands in defiance of his old professor as he lays about the truth about war. That cross on the wall behind him– what could that mean? 😉

The class stands to call him a coward. Milestone does a lot of great stuff in this scene; first, the boys here are all much younger men than any of the actors we’ve been following so far in the movie, driving home just how young they were when they joined and how desperate Germany is getting for troops. Also, throughout the scene where Paul tries to explain to them how they’re misguided, he’s never in the same shot as them, but always with the professor. This visual arithmetic keeps Paul separated from his former life and the passion he once felt in the classroom just as well as his words do.

Paul says goodbye to his mother forever. Yeah, not much to say other than it’s a beautiful shot.

Paul’s last friend in the war has died, and he stumbles off to the back. Milestone keeps the camera on the two indifferent medics who have become completely inured to the pain of the soldiers. Paul’s stunned silence and that loss of the film’s most paternal and warm character are a sure sign that even if Paul made it out of the movie alive, he’d have no connection to humanity left. His final few moments in the film are a yearning towards this, a freedom from the chaos of not only war but the depravity of a society that brought war. And it’s represented, naturally, by a butterfly.

Trivia & Links

- All Quiet on the Western Front is based on a 1929 novel by German writer Erich Remarque. He was apparently offered the lead in the film by Milestone, but wisely turned it down. Remarque’s book led to him being ostracized in Germany and he eventually ended up in the United States.

- If you didn’t like the movie, DO YOU KNOW WHO ELSE DIDN’T LIKE THE MOVIE? The Nazis apparently stormed screenings of this (including inciting panic and, ironically on some level, releasing rats into the theater) and got the film banned in their home country. They called it a horde of lies about the glory of combat. So, when you’re watching the scene where Paul goes back to his old classroom and is called a coward, historical hindsight gives us a better handle on exactly who those kids grew up to be.

- Okay, okay, the film’s detesters doesn’t just stop at Nazis, as the American Legion protested the movie too. So don’t feel too bad, I guess.

- Some movie connections for you: yes, there is a sequel (to both book and movie) called The Road Back. The movie was directed by James Whale and released in 1937; it apparently had quite a bit of anti-Nazi sentiment edited out of it at the behest of, well, the Nazis. The jerks.

- All Quiet itself was remade in 1979 as sort of a reaction to the Vietnam War. Most of the reviews I’ve read of it seem to be favorable, though the color photography and musical score make it sound a lot more run-of-the-mill that Milestone’s version.

- Modaunt Hall’s contemporary review in the New York Times is probably the longest I’ve ever seen him write, and he is simply radiating throughout. He even picks up on the bit with the boots, which, knowing Mordaunt’s usual writing, is pretty good. There’s also a contemporary news article about the film’s production, which helps you to realize the furor that surrounded its source material and the controversy that both the film and book stirred up in those who still clung to the glory of war.

- AMC FilmSite does a breakdown of the film, including full transcriptions of some of its more powerful monologues.

- The always reliable Movie Diva goes into the many different versions that the film has had released over the years, from having half its running time hacked off to having it retooled to use it as anti-Nazi and later anti-Soviet propaganda. This one pretty much has all the background info you could ask for.

- James Bernadelli over at Reelviews nails this one. I’ve mentioned it a couple of times before, but he’s the best one of those “I’m going to watch every Best Picture!” bloggers by far.

- James Ewing at Cinema Sights is someone who is always at least interesting to read, and this time he succeeds in spades. He does a great job touching on the visuals of the movie, and how they’re used to such great effect.

- The UK paper The Guardian has an excellent interview with the last surviving cast member of the film who reminices about the film’s making and the men he worked with.

- Mythical Monkey calls this one of the best films of the early 30’s and litters his article with details about the film’s making. It was produced for a million dollars, and brought back three. Not bad, not bad. He also rightfully points out that the cast’s relative youth (most themselves in their late teens) help to make the movie so powerful.

- DVD Verdict who isn’t usually known for their excellence in reviewing, has Judge Bill Giibron knock it out of the park. He does an excellent job in explaining that the film isn’t just anti-war because it shows you how awful combat is, but that it brilliantly contrasts war with the idealism associated with it. This is a good read.

- The movie was recently released on a cleaned up DVD and a Blu-Ray, and DVD Beaver has the comparisons for you. It’s some seriously impressive stuff.

- Thanks to its visibility, there is a boatload of awful, awful writing about this film. I’ve thoughtfully spared you most of it, though I wanted to call out one review that said, “it’s so anti-war that it almost undermines its message.” So it’s so anti-war, it makes you want to declare a war, because if it’s anti-war, then war is good…? I have no idea.

- The New York Sun talks about the source material and it’s relatively neglected state. The writer, Gary Giddins, also rather cunningly contrasts it with Powell and Pressburger’s anti-Nazi film from a decade later, The 49th Parallel. Both feature Germans as protagonists, though obviously in drastically different lights.

- Cliff over at Immortal Ephemera dives into the background of Louis Wolheim, who plays the grizzled old Kat. He was discovered by Lionel Barrymore, and made a name for himself as a heavy in silent movies like the 1920 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and D.W. Grififth’s America. This is a really good read.

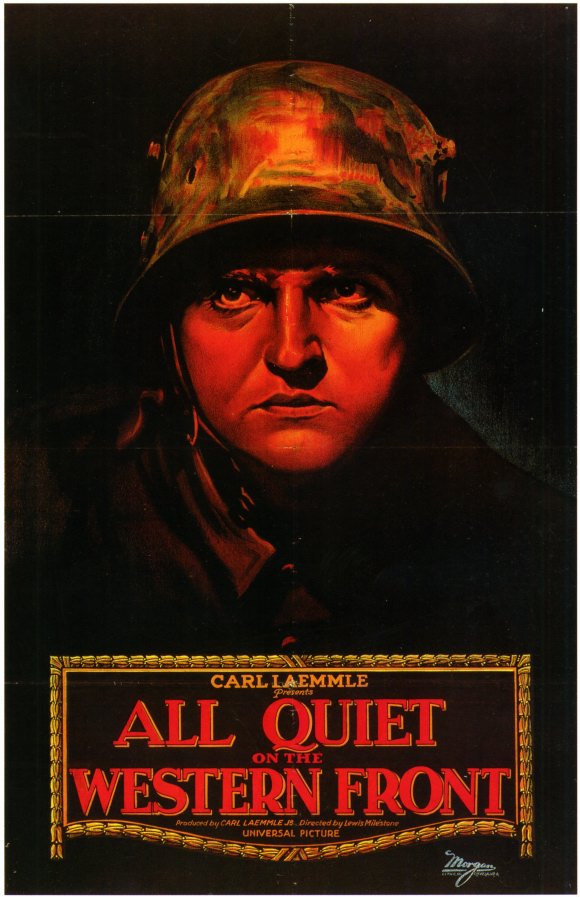

- The movie possesses one of the most iconic posters of the Pre-Code era, and it’s not surprising. Rather than emphasize the battles, or the large cast, or a bevy of other things, it simply focuses on the face of one soldier:

It’s a rather perfect mixture of anxiety, dread and anger. The loneliness and the darkness, too, speak volumes, as does the grim coppery red that highlights the piece. Very beautiful work.

Availability

- This film is available on Amazon on Instant Video, DVD and Blu-Ray, and can be rented from Classicflix.

8 Comments

Jamie Jobb · February 2, 2013 at 12:09 pm

You need a standing ovation for all the effort you put into this great post. Thanks and keep up your great digging before blogging!

Danny · February 3, 2013 at 3:02 am

Thank you! Kind words like that make it all worth it. 🙂

steve shuttleworth · February 19, 2013 at 7:09 am

I second that ovation. With so much dross on the internet, it’s a pleasure to read a literate, caring treatment of a truly great film. Thank you for your excellent work!

Danny · February 19, 2013 at 12:45 pm

Again, thank you very much! I really appreciate it!

swatopluk · August 3, 2014 at 6:36 pm

One interesting flaw this film has is that the uniforms seem never to get dirty (except in the training scenes at the start where it is the topic). This is in stark contrast to many contemporary WW1 films from Europe where the soldiers become almost unrecognizable due to the loads of dirt on their faces, helmets and clothes. If one sees a clean uniform there, it tends to be deliberate, marking the person wearing it as a REMF or a newbie.

Milestone’s film uses an interesting visual marker for passed time: the change in headgear. They start with pre-war Pickelhauben, go to the front with clothed-over ones, then remove the Pickel and later switch to the iconic Stahlhelm (that gets a few dents later on).

Danny · August 7, 2014 at 12:01 pm

Also very cool info. Thanks for sharing!

Chris · March 17, 2015 at 1:24 pm

Great website!

I saw this film as a kid and didn’t appreciate it; although, being a war movie, I watched it. I appreciate it nowadays!

Danny · March 18, 2015 at 11:42 pm

It definitely gets better the more you know and understand about movies. Glad you enjoyed it, and thanks for the compliment!

Comments are closed.