|

|

|

| Sam Spade Ricardo Cortez |

Ruth Wonderly Bebe Daniels |

Casper Gutman Dudley Digges |

|

|

|

| Effie Perine Una Merkel |

Iva Archer Thelma Todd |

Dr. Joel Cairo Otto Matieson |

| Released by Warner Brothers | Directed By Roy Del Ruth |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Sam Spade likes the ladies. More on that below.

- Homosexual subtext aplenty, with most of the film’s villains hinted at being in such relationships.

- Top billed Bebe Daniels is forced undressed under threats of being forcibly undressed by a group of men. She also takes a barely-concealing-much-of-anything bath.

- Spade was sleeping with his co-worker’s wife, so much so that she kept a kimono at his house for lounging post-intercourse.

- A stage whispered, “S.O.B.” is snuck in there. (Though I just read that somewhere, so I have no clue where it’s at.)

- The movie ends with a surprising amount of sympathy and affection for a woman who killed a man in cold blood.

- Refused reissue by the Hayes’ Office in 1936 because of its content. After that it was basically stuck in the vault for thirty years until the Code faltered and it could be shown again, whereupon it was retitled Dangerous Female to avoid confusing audiences with another movie named The Maltese Falcon (perhaps you’ve heard of it?).

The Maltese Falcon: That Thing Dreams Are Made Of

“You have a lot of trouble with your women, don’t you, Sam?”

The reputation of The Maltese Falcon is hard to ignore. The original 1930 detective novel helped define the atmosphere and tales of private investigators and the femme fatales that would later come to characterize so much of 1940s and 50s cinema. The preponderance of film noir fans and admirers, particularly in the 1941 version of the Maltese tale, have left the film’s first adaptation from 1931 to be often overlooked and just as often misunderstood.

The film stars silent-era heartthrob Ricardo Cortez as Sam Spade. For those of you coming on this review from your shiny new three-disk Maltese Falcon set or are just unfamiliar with Cortez in general, I’ve always adored this breakdown of his pre-Code career in Mick LaSalle’s Complicated Women:

[Pre-Code] actresses got away with murder. Literally. Loretta Young shot Ricardo Cortez in Midnight Mary (1933). Kay Francis shot Cortez in The House on 56th Street (1933). Kay Francis poisoned Cortez in Mandalay (1934). Dolores Del Rio stabbed Cortez in Wonder Bar (1934)

But wait. From that list it sounds as if the pre-Codes were merely open season on Ricardo Cortez, an oily character actor whose smoothness with the ladies often led to his downfall (on-screen). To be sure, Helen Twelvetrees had shot Cortez as early as 1931 in Bad Company, and in late 1934 he would mark the end of the pre-Code era by getting shot by Anita Louise in The Firebird (1934).

Basically, it’s just remarkable to watch a Cortez movie where he makes it to the end credits.

I think that’s important to point out since the movie’s Sam Spade fits perfectly into the Ricardo Cortez mold– a sly, unscrupulous devil with a big smile. Oftentimes, that smile makes him look like a shark, who just so happens to be dressed to the nines.

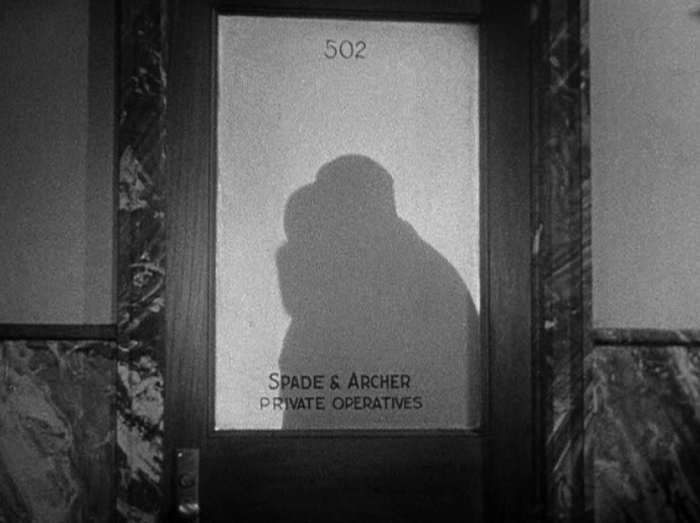

Set in fog-shrouded San Francisco, Spade is a private investigator. We meet him as a woman leaves his office after an embrace. We don’t see her face, but we do see her adjusting her stockings– immediately setting Spade up as a lady’s man. In less than the first three minutes of the movie (which, keep in mind, a minute and a half is dedicated to the credits and an establishing shot), we see Sam kiss one woman on the hand, plant one on his secretary Effie’s (Una Merkel) neck, examine Merkel’s posterior region not once but twice, and clean up his office after what must have been vigorous lovemaking.

But it’s quickly apparent that this bravado is covering up for something. Spade is living a life completely in the aesthetics — beautiful woman, beautiful suits, and beautiful apartment. It’s an attempt to bring order to his inner life by creating a perfect outer one. There’s something wounded and weary underneath that Spade does his best to obscure, a genuine yearning for a connection that he tries to repress. The facelessness of the first woman seems to express this– she’s not anonymous just because the movie’s being coy, she’s anonymous because she could be practically any woman and it wouldn’t matter to Spade. It’s the cycle that’s important, those vigorous sessions of lovemaking and then releasing them back into the wild before they get too close or in too deep.

I’m guessing the use of ‘private operatives’ here rather than ‘detectives’ or ‘investigators’ is a sly joke.

Spade’s womanizing hits a stopping point in the specter of his former lover, Iva (Thelma Todd). The wife of his partner, Miles Archer (Walter Long), Iva is possessive and enthusiastic, which is clearly the last thing that Spade wants. There’s no love lost between Spade and Archer before the affair even begins, and Sam doesn’t even seem to care if Archer does simple mental arithmetic to figure it out for himself. It’s easy to picture this as the reason why he fell out of lust with Iva– he’s had his fun, but her continued pursuit threatens to upset the nice routine he’s got going. Because it’s his partner’s wife, so much the worse.

Everything in Sam’s life seems nicely complicated at that point, but it only spirals out further when a woman named Ruth Wonderly (Bebe Daniels) walks into the office begging for help in finding her lost sister. Ruth claims that her sister has been abducted by a man named Thursby and wants him tailed in hopes of finding her. Sam’s a little too enthusiastic to take the job after getting a load of Wonderly’s assets, so the bitter Archer decides he’s going to tail Ruth and see what he can get out of it. When Archer turns up dead shortly past midnight, Spade is called down to Chinatown to get briefed by the detectives on the case. This is one of the first moments where the real Spade shines through, the man intimately familiar with the ugliness of the human condition. When the police ask him if he wants to look at the body, Spade snaps:

“What’s the use, Tom? You’ve looked at him. Nothing I can do to bring him to life.”

This scene also includes one of the more controversial aspects of the movie and a further peek into Spade’s head. On his way leaving the crime scene, he has a brief conversation with a Chinese merchant, in Chinese. Considering the movie is set in San Francisco, it’s not surprising that a private investigator would find it handy to know the language, but it’s again another look beneath Spade’s perfectly manufactured exterior. He clearly knows the streets, and though we know he didn’t much care for Archer, it’s easy to see that Spade is shaken by the incident– this is further emphasized when we next see him in his apartment, drunk and surly to the murder’s investigating officers.

The information the merchant imparts is also important to unwinding the end of the film, but we’ll get to that when we get there.

Tell us the truth, Ruth.

The police come to see Spade and tell him that Thursby has turned up dead as well– with Sam as the prime suspect. The next morning, Spade goes to confront Wonderly, only to find her evasive. She admits that she made up the tale about her sister– which doesn’t surprise Sam the least bit– but that she needs his help to track down an item. Puzzled by her story and still trying to puzzle out the angle on the killings, he agrees to take some of her money to track down this weird elusive item, which he soon learns is an invaluable statue called The Maltese Falcon.

There seems to be three groups of people in search of the bird, all interconnected with a history of not getting along too well with one another. Dr. Cairo (Otto Matieson), an effeminate man with a well coiffed Van Dyke, sticks Spade up in his office. Gutman (Dudley Digges), a portly, sweaty fellow with a lot of money, offers Spade tens of thousands in return for the bird. Then there’s also Gutman’s right hand man, Wilmer (Dwight Frye), whose panicky eyes under a big hat and coat hide a great deal.

And then there’s still Ruth. Sam is still trying to figure out exactly where and how he fits into this, and he catches on pretty quick that Ruth is only too happy to seduce him in hopes of currying favor. Sam won’t say no to a willing woman, even if he has the sneaking suspicion that he’s only digging himself a deeper grave. As Gutman notes:

“Ms. Wonderly’s admirers have been many, sir. And she has used them all to her great advantage.”

Don’t say no until you know her angle.

Spoilers.

Through a fluke, Spade gets his hands on the bird when a ship’s captain in possession of it stumbles in shortly before dying from a bullet wound. It seems that Ruth had smuggled it to the captain back in China, and then he’d brought it to deliver it to her. But if Ruth’s known where the bird was all along, then why was she paying Sam to find it?

The film climaxes in a tense night where all of the bird’s pursuers show up at Sam’s place. Cairo’s returned to Gutman’s fold, but there’s still a matter of tension regarding the bird. Sam will hand it over for some cash, and the man who murdered Thursby and the captain. Gutman outs Wilmer as the murderer, betraying him to save his own hide.

(Side note: I love the detail that Wonderly cheats at solitaire. It says so much about her character in one brief second.)

Things aren’t going as well as hoped.

The Falcon arrives in the morning, and the crooks, who’ve searched for the bird for years, greedily chip away at its exterior shell only to find, instead of a jewel encrusted charm, a layer of plain, blase concrete. Wilmer uses the opportunity to escape, while Gutman and Cairo stick up Spade and demand all of the money they’ve given him returned.

Outside of a few outliers, the violence in pre-Code movies aren’t the sustained action sequences we get regularly served today. The action is punctuated and brutal. Sam’s disarming of Cairo and Wilmer are over after a moment, illustrating his mastery of violence. That Cairo, Gutman and Wilmer meet their demise off screen is unsurprising, not just because their Quixotic quest for the bird has been fundamentally broken at this point, but the filmmakers know that the violence that the audience imagines is certainly more brutal than what we’d see on screen.

But that’s also because the real fireworks are left to be had between Sam and Ruth. Sam reveals that he’s known the whole time that Ruth was the one who murdered Archer, he just needed to find out why. She cries at him,

“Then you’ve been pretending. You don’t care. You don’t love me!”

And he looks away, trying to keep himself opaque.

“Oh, I think I do. But what of it?”

Final fireworks.

I love this moment, this genuinely honest scene of Cortez playing with the pattern on his chair, eyes down turned. It’s Spade’s most honest moment in the film:

“It’s easy enough to be nuts about you, too. But what of it? That’ll all pass. Oh, I’ll have some rotten nights. But they won’t mean anything. I’ll get over you in time.”

And that’s the closest we get to Sam in the whole movie. In many ways, Spade is the titular Falcon– a shiny, sleek exterior conceals an inner hardness. What we’re seeing may be Spade’s most vulnerable moment in not just the film, but in his entire life. There’s something real to his relationship to Ruth, you know, despite the fact it was based on an elaborate series of lies. It’s not that she murdered his partner as he’s pretty cool with that, but it’s her obsession for the Falcon, and her willingness to go to any length to get it. He doesn’t understand it and envies that kind of focus in life.

But that doesn’t last. Spade turns her into the police, as much out of a sense of obligation as the fact he can’t just reconcile the feelings he has for a killer. Ruth is put in prison for who knows how long, and Spade is given a job with the District Attorney’s office– another shiny, prominent position that will feed his own vanity. He has the prison matron promise to give Ruth the best things she can for her prison term, but the truth is that both of them are trapped: Ruth by her actions, and Spade by his inability to break with his intense desire for an exterior perfection. He’ll go on with his love affairs and his new office and all the privileges that brings, but he’ll never be in that moment– that exposed– ever again. Whether he likes it or not.

End spoilers.

(Insert Dragnet theme)

The biggest flaw in The Maltese Falcon would have to be the lack of tension– though that may be the wrong word for it. Still an early talkie, Director Roy Del Ruth (Blonde Crazy, The Mind Reader) has trouble keeping the plot in focus. The sudden appearance of the ship’s captain in Spade’s office is baffling, and Wilmer’s appearance is quite late in the movie, considering just how integral he turns out to be to the plot.

But that’s my biggest, and probably only complaint about the picture. The Maltese Falcon is a corker of a film. It’s an interesting study of a man that’s not just stated, but explored in its many modulations, a riddle that examines what makes a person a person and what makes a statue of a black bird seem so unique and extraordinary– and how both of them turn out to be something much more mundane.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- Famously (at least to me, I guess), this movie inspired the title for The Dame in the Kimono by Leonard J. Leff and Jerold L. Simmons. It’s an excellent book about the history of the Motion Picture Production Code. It gets my highest recommendation.

- Since the movie couldn’t be reissued and Warner Brothers wanted to cash in on Hammett’s popularity, the movie was remade twice. Once as a bawdy (and awful, truly awful) comedy called The Devil Was a Woman with Bette Davis and Warren William, and again in 1941 with Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor.

- While this is the first version of The Maltese Falcon to arrive on screen, it’s the third adaptation of a Dashiell Hammett story. The extremely obscure 1930 film Roadhouse Nights is loosely based on his book Red Harvest while 1931’s City Streets is based on one of Hammett’s short stories. The last pre-Code adaptation of a Hammett work would also become one of the most infamous adaptations of all his works — 1934’s The Thin Man.

- TCMDB talks about the film’s censorship battles over time, and how the movie dialed up the sex (and tried to get away with it).

Director Roy Del Ruth’s staging, if anything, added to the film’s sexual mystique. When Spade’s female client spends the night in his apartment, the writers had Spade say that he would sleep on the couch to appease the censors. But when the woman wakes up the next morning, there’s a clear indentation in the pillow she’s not using to suggest where he really slept.The writers added a scene in which Sam, suspecting his client has stolen $1,000, makes her strip. Although her undressing was kept out of camera range, Spade gets a few articles of feminine clothing thrown in his face.When the head of the Production Code Administration objected to the scene, studio production chief Darryl F. Zanuck said that since she never threw her underwear at him the audience would know she wasn’t naked. Although the film’s gay element was relatively subdued, there’s clearly something sexual about the way Gutman fondles Wilmer’s cheek while setting him up to take the rap.

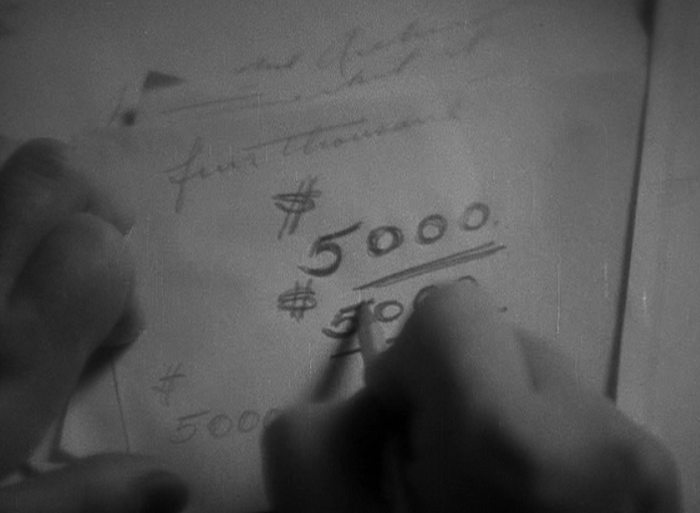

Really needs a “Mr. Sam $5000” to complete it.

- Considering the 1941 Maltese Falcon is often credited as one of the greatest films of all time, it’s often compared with the other two versions of the movie. Here’s an excellent (but be warned, fairly academic) rundown called The Three Sam Spades by Philippa Gates that discusses how the different film’s portray masculinity, along with what they could get away with and what they couldn’t. An excerpt [warning: contains spoilers]:

In the Code-era films, the heroes are more wary of Valerie and Brigid as femmes fatales: Brigid because she might bring about Spade’s demise through death and Valerie because she wants to bring about the demise of Shayne’s desire for “an awful lot of fun” through marriage. On the other hand, Ruth, in Dangerous Female, seems to represent a departure for Cortez’s Spade rather than his demise: one cannot help but feel that Ruth might actually be Spade’s equal and match if only she did not have to go to prison for murdering his partner. After all, we can assume that Spade has known of her guilt since the beginning. At the end of the film, it is revealed that the man in Chinatown told Spade that he saw Archer’s murderer; why then does Spade engage in a relationship with Ruth? Consorting with Archer’s murderer does not seem to trouble Spade; deciding whether to give her up to the police does. When he visits her in prison and tells her that he will wait for her to get out, one is tempted to believe him (he will undoubtedly entertain himself with other women in the meantime). As Everson suggests, with the Code not being enforced in 1931 and Hammett’s novel not yet an iconographic text, the screenwriter and/or director could easily have concocted a happy ending without arousing anyone’s ire. Maude Fulton (the screenwriter) and/or Del Ruth (the director) must have desired a hero that, despite his questionable motives and seeming self-serving nature, makes a sacrifice in order to see justice served—and, in this sense, all three films are similar. However, unlike Bogart’s wartime Spade who is embittered by his involvement with women, Cortez and William’s Depression-era Spades are allowed to enjoy their relations with many different women and do so without guilt or consequence.

- I hate reusing sources to discuss a movie, but, again, Philippa does a brilliant job discussing the piece of the original novel that’s missing from all three screen adaptations: the story Spade tells Brigid about an old coworker of his named Flitcraft. Many critics assail this, but Philippa does a great job of pointing out how this realigns the film’s meanings from that of the novel’s [again, spoilers]:

In Hammett’s novel, it would seem that Spade learned nothing from Flitcraft’s story. Like Flitcraft, he may have avoided his falling beam and lived unpredictably for a short while but, in the end, Spade, like Flitcraft, falls back into the same old life. Rather than ending with Brigid’s being taken away as all three films do, the novel offers one more scene in which Spade returns to the office. Effie is upset with Spade: “You did that, Sam, to her?” Effie cannot believe that Spade would betray Brigid, and one has the sense that Spade questions his decision too. When Effie informs him that “Iva is here,” and he replies, “Well, send her in,” Spade returns to his familiar life pattern and relationships. As Ilsa J. Bick suggests, Hammett’s story—like Flitcraft’s—is about the circularity, or “compulsive repetition,” of living life: the villains want to continue to chase the falcon, and Spade ends up where he started. In keeping with hard-boiled fiction’s drive toward realism, Hammett seems more critical of human nature and his hero than Hollywood; the ending of his Maltese Falcon would suggest that people do not ever really change, whereas Hollywood—even in film noir—assures us heroes do . . . and for the better.

My other major complaint about this movie would have to be not enough Dwight Frye. But that’s my take on most early 30s movies.

- The Maltese Falcon itself was supposedly inspired by a sculpture called The Kniphausen Hawk. History Blog reports:

Hammett was apparently inspired by the Kniphausen Hawk, a ceremonial pouring vessel made in the late 17th century for Count George William von Kniphausen. It stands on a rock base and is encrusted with garnets, amethysts, citrine quartzes, emeralds, turquoises and sapphires. It was bought by the Duke of Devonshire in 1819 and has been part of the Chatsworth collection ever since.

- Unfortunately there’s no great Immortal Ephemera post about this film to put all of my work to shame this week (as of yet, at least), but he does have biographies of supporting players Dwight Frye, Dudley Digges, and Una Merkel.

- Dr. Macro is here to serve you with posters and stills and even audio adaptations of The Maltese Falcon. Unfortunately, the movie’s posters are less than impressive.

Del Ruth has a lot of interesting shot compositions in the movie, often using characters to obscure one another. Oh, and shots like this. This shot is interesting.

- The New York Times’ original review from 1931 is spoiler and praise-filled.

- I read a lot of reviews for this one that debate what ‘film noir’ is or isn’t, so I’m just going to say this about it: I don’t give a crap. Also, if you really want to know how this compares with the 1941 version of the movie that I haven’t seen in well over a decade, please check out literally every other review on the internet.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 Comments

Cliff Aliperti · December 1, 2014 at 1:28 am

Danny, thank you for the links (triples, nice!) and (crazy!) high compliment, but my only issue with your post is picking on Satan Met a Lady with Warren and Bette — It bears repeated viewings to flush the later classic from your mind, at least that’s how my head worked it, but damn it, after 8 or 10 times down that pike, I find it hilarious!

By the way, since that 3-movie set came out I think I’ve only watched the Bogie version once, after it first arrived, because I’ve fallen so in love with the alternate worlds of the other two movies. This movie is everything a pre-Code Maltese Falcon should be, isn’t it?

I’d love to know how it felt to experience the three in their proper order, as they were released with years spaced in between. Of course, I probably wouldn’t be here anymore if I did, so I guess I wouldn’t love it that much.

Danny · December 1, 2014 at 10:52 am

Cliff, don’t bring your Satan Met a Lady Stockholm syndrome stuff in here. 😛

I think it would have been interesting to see those over a twelve year period, and each definitely shows the influence of when it was made. I think I’m more content to just watching them in a row after I grab the disks from the library again, though. Sadly, my couch is just more comfortable than time travel.

doriantb · December 2, 2014 at 2:56 am

Danny, the 1941 version (and the best, for my money!) is the best version, but the first version is always well worth a look to also see the different early versions. I must also admit that SATAN MET A LADY just because it’s so goofy and because young Bette Davis, Warren William, and Marie Wilson. In any case, I enjoyed your post! 😀

Danny · December 9, 2014 at 10:53 am

Thanks Dorian. I’m glad you enjoy all of the movies, even if I find SATAN completely incomprehensible.

ladylavinia1932 · September 22, 2016 at 12:26 am

When I first saw this version of “The Maltese Falcon”, I had approached it with the mindset that it would be crap. I was surprised to see that I enjoyed it, even though I found the pacing a bit slow. Then I saw it for a second time . . . and enjoyed it even more. For me, the 1941 movie tops it in regard to pacing and sharper dialogue. Otherwise . . . hmm, I don’t know what else to say.

Comments are closed.