|

|

|

| Carol Joan Blondell |

Lawrence Warren William |

Trixie Aline MacMahon |

|

|

|

| Polly Ruby Keeler |

Brad Dick Powell |

Peabody Guy Kibbee |

|

|

|

| Barney Ned Sparks |

Fay Ginger Rogers |

Singer Etta Moten |

| Released by Warner Brothers | Directed by Mervyn LeRoy |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

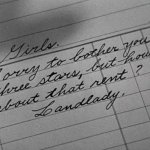

- One of the musical numbers is called “Pettin’ in the Park.” If you’ve seen it, you’d know it. More on that below.

- “I look much better in clothes than any of ya. If Barney could see me in clothes…”

“He wouldn’t recognize you!”

- Trixie cracks, “What does he use? I’ll smoke it too!”

- Trixie steals Fay’s clothes, giving her a slap on the rear when she tries to resist:

- A bootlegger carries around a violin case full of booze.

- “The kind of man I’ve been looking for– lots of money and no resistance!”

- Joan Blondell offers tips on how to properly groom (and what to wear for it):

- It’s all about the Depression, dearie.

Gold Diggers of 1933: Cheap and Vulgar

“Wait a minute! Listen. He’s got it. Just what I want! Don’t you hear that wailing, wailing… men marching, marching… marching in the rain. Jobs… jobs… gee, don’t it get ya?”

Let me go back to 2006– a hoary time to be sure. I was in the process of moving to Denver for a variety of reasons. My friend, Will, already lived there, and gave me and my girlfriend of the time free run of his apartment. After we spent the morning walking around Aurora (yay, Best Buys and strip clubs), we crashed and flipped on the TV.

I’d been a fan of Turner Classic Movies for a while before that, having grown up with the network. And I’d unsuccessfully tried to get the channel in college– it was channel 400, making it part of the $150-a-month club of cable packages that no college kid can rightly afford.

But back to that sunny Denver afternoon. Ben Mankiewicz introduced the movie, and while I can’t remember the words or phrases, it certainly enticed. Watching Gold Diggers of 1933 is a hell of an experience– silence, laughter, and then the occasional “holy shit, look at that!” mixed with “how the hell did they do that?” are all frequent occurrences. Me and the girl sat stunned after the feature ended, if a bit shaken. How often on a sunny afternoon are you shaken out of your middle class complacency and thrown full heed into history?

Gold Diggers of 1933 is, I argue, the most complete document of the Great Depression and pre-Code Hollywood. While there are other films that more bleak or sexy or funny, Gold Diggers is the perfect blend of all of these elements. Taking the disparate urges of the era, from the poverty and starvation to the liberated sexual attitudes and sophisticated sense of humor, it manages to balance them to great success. The movie is weird at times, as weaving this together isn’t easy, but in its plot and execution, it aims for finding a sense of grace about the times, a mixture between hope and the dogged understanding in just how hopeless the whole morass could be.

Besides just documenting these foibles, their reverberations are built into the film’s structure itself. It floats between fantasy and reality, but never finds a solid line between both– even on stage, the Depression creeps in, while, after a big theatrical success, high society glitz intersects with the real world. The film’s directors, Mervyn LeRoy and Busby Berkeley, take measured pains to make this movie about the Depression– both the experience and the psychological effects– but with measured breaks. So by the last frame when you see Blondell’s outstretched hands begging for mercy towards the forgotten men of World War I, you’ve experienced the highs and lows of the world at large.

Let’s talk about the plot, since it’ll make more sense from there. But first we have to start with the film’s opening number, one of the most famous musical setpieces in all of cinema history and for good reason.

“We’re In The Money”

The film starts off with the audience immediately thrown into the gaudy, nutso “We’re in the Money” number. Even the most cursory documentary on Hollywood’s history will feature a moment of this episode’s excess, usually used as an example of the escapism of the Depression Era films’ modus operandi. Of course, out of context, that throws people off– hell, it threw me off the first time.

In context, though, the number itself is devastating. Let’s take a look at a chunk of the lyrics really quick:

We’re in the money, we’re in the money.

We’ve got a lot of what it takes to get along!

We’re in the money, the skies are sunny…

Old man Depression, you are through, you’ve done us wrong!

We never see a headline, ’bout a breadline today…

And when we see the landlord,

We can look that guy right in the eye!

What’s interesting about the number isn’t that it isn’t about traditional American greed for riches and , but it’s not about greed or desire– it’s about dignity. Being able to look your landlord right in the eye isn’t about having the ability to be on the same level as your creditors, but being able to walk and make your way into the world. This will figure heavily into the first act of the picture.

As she emerges from the giant phallic Scrooge McDuck vault in an outfit made from cardboard coins, Linda thought, “Gee, I’ve finally made it!”

While these lyrics are being belted out with maximum gusto, a bevy of scantily clad chorus girls (with Ginger Rogers in the lead) model their coin-based attire, including a fashion show that give a libertarian fetishist wank material for a year.

The second verse of the song does something interesting in that it switches up the lyrics with a reprise in Pig Latin. Besides the discongruity of hearing Ginger Rogers say what sounds like ‘anime’ to modern ears, this serves a purpose. The first is to take the lyrics and contort them beyond recognition– taking the ode to capitalist wealth and a yearn for decent dignity through materialist riches and making it into childish gibberish, perhaps acknowledging how little that possibly does matter. At the same time as the Pig Latin verses, we’re treated to an extreme close-up of Rogers’ face, almost rendering it grotesque (I mean, it’s still Ginger Rogers’ face, but still). It becomes omnipresent, briefly taking the audience into a completely different type of surreality.

The musical number ends not with a finale, but with a crash as the sheriff department raids the show. That leads to another theme of the movie, that audiences could certainly latch on to at the time: hard work getting deferred right when it seems to be paying off. The juxtaposition between the chorus girls singing the virtues of financial security as the show is closed by its creditors isn’t lost as we’re quickly introduced to our droll leads– chorus girls Carol (Joan Blondell), Polly (Ruby Keeler) and comic player Trixie (Aline MacMahon). They’re also roommates, and we follow them back to their tenement after a brief insert showing us just how many theaters are are open on Broadway– none.

We’re quickly apprised of the personalities. Carol is direct and passionate. Polly is romantic but reserved. And Trixie is that special kind of woman who is wry and devious in a dangerous mix. They’ve all seen the tops of society, but with no show on and no work, Trixie is stealing milk from the window sill of their neighbors. They don’t even have a full set of clothes to dress up in when it’s rumored that producer Barney (Ned Sparks) will finally get a show off the ground again; they have to steal an outfit from Fay (Rogers) requisitioned from her job at the druggists.

Carol is sent in the duds to go see if Barney is on the level, and she calls back to the girls. In an interesting reversal, when we cut to her on her end of the phone, she’s choking up. Initially, the audience will leap to thinking that the rumor was just that. But, instead, Carol is literally so excited about the possibility of work, she’s almost in tears. She brings Barney home, where he announces he has the theater set and, with the girls, has the cast, too. After hearing Polly’s romantic partner, Brad (Dick Powell), playing the piano across the alleyway, Barney has the music, too. Now all he needs is the money.

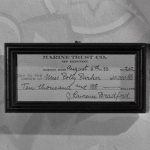

Everyone is instantly defeated, but Brad offers to put up $15,000 for the show. No one understands how a songwriter in the tenements could get the money– Trixie thinks he’s a bank robber on the lam– but he comes through. He even performs in the show over his own objections when he discovers that it’ll go under without him. And the show within the movie kicks off with one of the craziest, sexiest things you may ever catch on the silver screen.

“Pettin’ in the Park”

Unlike “We’re in the Money” and later “Remember My Forgotten Man”, there isn’t a lot of depth to “Pettin’ in the Park.” But, good god, that doesn’t subtract from it one bit.

The number begins with Brad and Polly on the stage. As he reads a book called Advice to Those in Love, he learns the best way to relax after work is in the open air under the starry sky… and taking someone sweet along isn’t bad. The two tap out their brief seduction, with Powell the over-the-top seducer and Keeler mixing gee-whiz shock with a few sly smiles. They croon with full playful enthusiasm:

“Pettin’ in the park!” “Bad boy!”

“Pettin’ in the dark. Bad girl!

First you pet a little,

Let up a little, and they you get a little kiss.”

Of course, the two hoofing it up on the stage isn’t enough for this or any other Berkeley number, so a random box of Animal Crackers that Polly was carrying transitions to a zoo and a fall scene. We’re taken across dozens of benches with other petting enthusiasts, all varying in not only age, but in race as well (hey, it’s a Warner Brothers picture). Truly, “petting” is for everyone.

The number gets pretty silly for a bit, as Polly decides to make a break from Brad (apparently he was getting a bit beyond petting in the back of a taxi) and she decides to take roller skates home. A line of roller skating police officers, taking a break from violently beating up people I’m sure, give a hearty laugh as she leaves before a baby (Billy Barty) shoots a spitball at them. Then it’s time to beat the crap out of a baby. Luckily, the kid ducks and– since this is a comedy– they skate right over him.

We’re taken through the seasons, giving the Berkeley chorus girls a shot in cute winter outfits before we’re taken to spring and the film’s resolution. Things have been reconfigured in this new season to an elaborate deco park. The couples are no longer cute and varied, but a number of identically dressed men in women– the men in dapper suits and straw hats, the women in see-through dresses and straight black stockings. A rain storm breaks out, sending everyone scurrying. The women hide behind a thin sheet and undress, leaving not a whole lot to the imagination– but just enough to count.

Between the playful and coy lyrics, it’s hard not to be enchanted by the number. Jefferey Spivak, in his book Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley, succinctly explains the wonderful balancing act this number pulls off:

“Pettin'”– as term or act– is never defined explicitly. Adults possessed more worldliness in the Depression years than is routinely attributed to them. They often sought relief from their Depression doldrums not with pure entertainment, but with diversions that were impure and brazen. Buzz, Jack Warner, and the audiences of 1933 were partners in this little act of complicity that allowed the overtly blue nature of the number to remain in the picture unexpurgated. As for the children who watched Buzz’s pretty pictures unfold, the only thing they took away from “Pettin’ in the Park” was the imitative toddler named Billy Barty, the pea-shootin’ marksman.”

What I like about the number is that it’s all about the sexual back and forth. As the two singers interact, they playfully banter, “Bad boy!” and “Bad girl!”. There are gambits and retreats, all enhanced by the song’s celebration about the eroticism of the naughty and forbidden. Which, hey, pretty much describes the appeal of this entire era of Hollywood.

With the number wrapped up, Brad’s identity is exposed: he’s not a crook, but an heir to a fortune! And now it’s time to smoothly segue from the Depression and naughtiness of the film’s first half, away from Polly and Brad and towards Carol and Trixie’s misadventures in a new, gleaming fantasy world.

So we’re at the halfway point in the movie now (and, dear god, I hope at least the halfway point in the review), and it’s time for the top billed player in the film to finally show. Warren William arrives as Brad’s older brother, Lawrence. He’s accompanied by the family lawyer, Peabody (Guy Kibbee). The two show up to warn Brad to break things up with Polly, but he refuses. Kibbee, playing a couple of IQ points above his usual buffoon (though still as gullible as ever), warns:

“I remember in my early youth, I trod the primrose path on the great white way. There I learned the bitter truth that all women of the theater were chiselers. Parasites. Or, as we call them, gold diggers.”

With Brad refuting them, they head to Polly’s place only to find Carol there. And Lawrence’s chances of resisting her goes about as well as you can expect:

Lawerence and Peabody mistakenly think Carol is Polly, and offer to buy her off. Incensed, Trixie and Carol decide to have their fun instead and take the two saps for a ride. All goes smoothly until Carol falls for Lawrence, even after he assures that he’s still seeking to break up Polly and Brad despite the chemistry he himself is showing with a showgirl.

There’s a lot of fun banter and naughty stuff in this section, as Trixie’s obvious manipulations of Peabody are a delight to watch, as is Lawerence finally losing all resistance. Even as he declares that all showgirls are “cheap and vulgar”, he loses himself in Carol’s presence. Even when Trixie sets him up to think he’s had a one night stand, he returns and admits his feelings once he understands Carol’s true character. And, in my favorite bit, threatens to kiss her every time she says “Cheap and vulgar.” And say it she does.

We return to the theater for the film’s resolution and last two numbers.

“The Shadow Waltz”

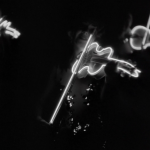

“Shadow Waltz” is an oddity for the film, as it’s undeniably elegant and beautiful. It’s visual poetry, a far cry from the playful vulgarity that runs throughout the movie. It strives for a kind of elegance, a soft, enchanting melody that gives the film’s classier fantasy side one last push.

With Powell in a suit and Keeler in a platinum blonde wig, we’re soon watching dozens of chorus girls in hoop skirts playing violin to the gentle melody of the tune. Each violin is also outfitted with neon tubes, so we’re treated to the women twirling in the dark. Berkeley even kicks it up a notch, having the women form a giant violin with a large neon bow cutting across to heighten things.

“The Shadow Waltz” lulls you. The lyrics themselves aren’t especially deep or meaningful, promising love from afar and ‘in the shadows’, a hint of romantic yearning that wishes to bring someone fully to life through their love. It’s sweet, kind and entrancing.

In the climax, Lawerence’s bluff to save his brother from Polly fails, and he readily admits defeat. All three of the couples are happy and either married or soon to be. It’s a little easy, but that feeds into the last bit of fantasy in the film. We get this one easy, because the next pill the audience is asked to swallow is going down hard no matter what.

“Remember My Forgotten Man”

Presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt had coined the term “Forgotten Man” in a speech in April 1932, using it to allude to the World War I veterans for whom prosperity had left behind and now suffered from unemployment. From the speech:

It is said that Napoleon lost the battle of Waterloo because he forgot his infantry–he staked too much upon the more spectacular but less substantial cavalry. The present administration in Washington provides a close parallel. It has either forgotten or it does not want to remember the infantry of our economic army.

These unhappy times call for the building of plans that rest upon the forgotten, the unorganized but the indispensable units of economic power, for plans like those of 1917 that build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.

Roosevelt’s remarks were in response to January’s emergence of the Bonus Army, a mass collective of 25,000 veterans who’d descended upon the nation’s capital. They demanded a payout of bonuses that were promised them for their service in World War I, and, when rebuffed by Hoover, setup a massive camp on the outskirts of the city. By July, the Hoover Administration would send first the police and then the army to terrorize and scare off the gathered veterans (other places use the term ‘evict’, which is far too sanitary). The military action resulted in over 1,000 being injured and two being killed. The handling of the Bonus Army was a major P.R. blunder for Hoover, and helped solidify his doom in the polls that November.

Roosevelt’s phrasing stuck in the public consciousness and epitomized how many felt about their place under an unsympathetic government. Hoover’s treatment of the Bonus Army seared the minds of Hollywood and beyond, an indictment of the government’s coldness that would influence dozens of movies, especially coming from Warner Brothers. These included films like Heroes for Sale, Wild Boys of the Road, Mayor of Hell and Massacre, all of which view emotionless state authority with a jaundiced eye.

Warners usually kept their musicals and social commentaries separate. While you can certainly see the Depression in 42nd Street, it wasn’t front and center. Who wanted to be brought down to earth in a genre that reeked of glamour? But that’s not reality, and that’s not 1933 Warner Brothers. Berkeley, who’d served in World War I, takes the measured march and paints an exacting canvas of hopelessness for the “Forgotten Man” number.

Remember my forgotten man.

You put a rifle in his hand.

You sent him far away,

You shouted: “Hip-hooray!”

But look at him today…

Carol plays a streetwalker who’s definitely on the low end of society. She’s dressed in rags and watches with sadness and frustration as hungry men wander the streets and get hassled by cops. Her song is soon met with the deep accompaniment from Etta Moten as the scene fades from the dark street to the memories of the soldiers of the First World War. They start marching under patriotic banners, return injured and alone and are soon seen in the breadline.

The number climaxes with an enormous arch of soldiers looming over the mass of homeless men and their desperate women. Blondell (dubbed in the finale by nightclub singer Jean Cowan) wails on, aiming for the gut as the film draws to a close:

‘Cause ever since the world began

A woman’s got to have a man!

Forgetting him, you see,

Means you’re forgetting me…

Like my forgotten man!

The number wouldn’t work half as well without that woman’s perspective coming through from Blondell and Moten. The crap mobility for women at the time meant that they were reliant on the men on their lives. The song shows firsthand the problems of not just what their husbands, brothers and fathers were experiencing, but what it was like being completely helpless in the face of it. The Great Depression wasn’t just a sociological shakeup, but a psychological one. The rules on pride were upended to a cataclysmic effect, destroying households and families.

“Remember My Forgotten Man” comes closer to explaining this awful thing that the Depression was more than any cold statistical number or lengthy documentary could. The song is a plea for dignity to, at the time, an audience who not only knew what the song was saying but felt it in their bones. It’s a rousing finale, one of the greatest combinations of cinematography, music, singing, choreography– hell, you name it. It’s unnerving and masterful.

If my enthusiasm hasn’t let on by now, everything about Gold Diggers of 1933 is my jam. All of the actors and actresses are at the top of their game, while LeRoy and Berkeley have the perfect meshing of temperaments.

Gold Diggers of 1933 is one of those movies that affected my life in ways I can scarcely even understand myself. That afternoon in Denver, watching TCM, I fell in love with Busby Berkeley and rediscovered a personal love of musicals. More than that, Turner Classic Movies, which I’d always regarded as a nice supplement to the video store, took on a more immediacy in my life. Since then, through the channel I’ve discovered hundreds of great films through luck and magic. The internet turned the channel into a community, and the rest is history.

A channel that helped me to discover one of the most perfect films ever made– that’s Gold Diggers of 1933 for those of you who lost track– is one that I owe plenty.

Gallery

Click for big!

- Off to war.

Trivia & Links

- Though there are no direct sequels in the series, it follows two other movies based on the same play, Avery Hopwood’s The Gold Diggers. Those films were The Gold Diggers (1923) and Gold Diggers of Broadway (1929). The success of this film lead to several followups, Gold Diggers of 1935 (1935, with Powell again), Gold Diggers of 1937 (1937, with Powell and Blondell), and Gold Diggers in Paris (1938, with, uh, Rudy Vallee).

- There are a number of in-jokes in the film. Barney trots out a few early, such as when he hires Brad and declares, “I’ll cancel my contracts with Warren and Dubin, they’re out!” Harry Warren and Al Dubin wrote the music for the film. He also tells Brad, “You and Polly would make a swell team– like the Astaires!”, referring to then-popular dancing sensations Adele and Fred Astaire. Lastly, in one of the film’s bonus features, they point out that the snooty juvenile who’s been doing his job for 18-years may be referencing Dick Powell’s seemingly endless adolescence on the screen, a reputation he wouldn’t shake until Murder, My Sweet.

- Another funny bit– when Fay enters the crowded room where Barney has assembled the showgirls near the beginning of the film, she adopts a bit of a British accent, much as her Anytime Annie character has done back in 42nd Street. Irritated, Barney waves her to sit down.

- Also in that category: one of the stagehands calling for the final “Forgotten Man” number is choreographer Busby Berkeley himself:

- Blondell and William were also teamed up in the other truly pre-Code comedies Goodbye Again and Smarty as well as in Three on a Match. Keeler and Powell shared ten films, including pre-Codes Footlight Parade and Dames. Blondell was in those last two as well.

- Also: if you want to see Gold Diggers of 1933 but made with half the budget, no stars, and directed by the guy behind The Mummy, check out Moonlight and Pretzels.

- Basically, anything you could want to know about the behind-the-scenes background on this film can be discovered over at TCMDb. I’ve got a few more tidbits to add, but definitely check their stuff out, too.

- One more cute bit from Spivak’s Buzz:

To get those great top shots, Buzz used a wide-angle lens when he was sixty feet up. But there were many times he wanted the camera higher than the ceiling allowed. Buzz took aside some studio craftsmen and told them to bore a hole through the roof. Newly drilled holes appeared in five different soundstages. The camera, no longer subjected to the ceiling’s limitation, was covered with a tarpaulin once it escaped the physical boundaries of the soundstage. “The front office was a little upset,” said Buzz, possibly understating their position.

- There’s no reprise of “I Want to Sing a Torch Song” in the film (other than Trixie belting it in the bathtub), and it was apparently cut from the final print. The number, sung by Ginger Rogers, survives and can be found on the Lullaby of Broadway CD. The only hint of it left in the picture is a long establishing shot of the nightclub with who appears to be Rogers standing in front of the piano in the center.

- Included on the Warner Brothers DVD are a number of fun shorts and documentaries. Let’s dig in, shall we?

“42nd Street: From Book to Screen to Stage” is actually about, uh, 42nd Street. Not sure how it ended up on this disc. I’ll talk more about it when I review that film.

“Gold Diggers: FDR’s New Deal… Broadway Bound.” This is a lot like the above piece in that it’s an in-depth piece about the film. Well worth a watch.

A few short films:

“Seasoned Greetings” is a cute, 20 minute short about a shopkeeper who realizes there’s money to be made in “Talking Greeting Cards”. Starring Lita Grey, the short contains covers of “Petting in the Park” and “I Want to Sing a Torch Song.” The last third, which involves young Sammy Davis Jr. eating a chocolate record and accidentally having his stomach start belting out “St. Louis Blues” could put a few people off, but I thought it was rather cute.

“Rambling Round Radio Show 2” is a number of musical numbers just strung together. Despite the 1932 date attached, the audio is pretty scratchy, and none of the bits stand out.

And then some cartoons:

“I Want to Sing a Torch Song.” This short is a whirlwind tour through radio land with plenty of caricatures of film and radio stars. The cover of “Torch Song” is surprisingly jazzy, and we even get impersonations of Greta Garbo, Zasu Pitts (!), and Mae West belting out verses. You also get cartoon Cagney belting Blondell, if only to make it even more topical. Well worth a watch.

“We’re in the Money.” This Merrie Melody cartoon features a bunch of toys and other inanimate objects in a department store coming to life and singing the titular tune. It also includes a brief parody of Mae West and short appearances by Laurel & Hardy’s decapitated heads. For some reason.

“Pettin’ in the Park.” Uh, it starts off with a police officer and a girl petting in the park before it turns into some sort of bird Olympics. Things used to be weird, man.

- The film’s trailer:

- This review is part of the TCM Discoveries Blogathon hosted by The Nitrate Diva. Take a look and catch plenty of other reminisces about bloggers and their love for Turner Classic Movies!

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- Selected for the National Film Registry in 2003.

- This film is available on Amazon via DVD or digital copy. You can also get in a Busby Berkeley boxset with 42nd Street, Footlight Parade, Dames, and Gold Diggers of 1935.

- And, of course, you can occasionally catch it on Turner Classic Movies.

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 Comments

Ben Frey · September 18, 2015 at 5:11 am

Footlight Parade may edge this one out slightly as my favorite Warner Bros. musical, but they’re pretty close. Pretty much the same cast, plus Cagney. Ned Sparks is in my top 5 favorite character actors list (Frank McHugh is number one – another point for Footlight Parade). It’s amazing how the best of them could get by with one schtick film after film and never lose the audience. And Ruby Keeler – I once saw her tapping described as ‘stepping on ants’ (can’t remember where I read it). But she herself said, ” It’s really amazing. I couldn’t act. I had that terrible singing voice, and now I can see I wasn’t the greatest tap dancer in the world, either.”

Great review Danny.

Danny · January 7, 2016 at 11:52 pm

I still like Ruby Keeler. I find her charming and bubbly much in the same way Powell is. But I think I’m alone there.

brianpaige · September 18, 2015 at 7:18 am

I saw this movie right around Christmas in 1995, a few months after first getting TCM in my area. They had a Berkeley festival that week and I saw several of the other ones from that era. GD of 1933 actually used to be pretty hard to come by, as were all of the Warners 30s musicals (aside from maybe 42nd Street). Pretty much everything you said about the movie is 100% true. When it was over I just kind of sat there stunned. For the first hour or so I was highly entertained, but the 1-2 punch at the end of Shadow Waltz and Forgotten Man just amazed me.

This movie would be an excellent romantic comedy even without the music. I also like Footlight Parade and Dames (which should have just been GD of 1934). Footlight Parade is almost as good as Gold Diggers but I just think GD of 33 takes you in so many places emotionally that it gets the nod.

Danny · January 7, 2016 at 11:57 pm

I think that’s what I appreciate most about the WB/Berkeley pre-Code musicals– they work just as well without the music, but the music adds a layer of depth to the proceedings. Too often musicals just use them either as an opportunity to break up visual monotony or to simply blatantly talk about a character’s feelings. Gold Diggers, like Dames, 42nd Street, and some of the other greats, like Singin’ in the Rain, see the musical numbers as a way to brashly entertain while quietly revealing a depth to the film’s world that can’t be conveyed through dialogue.

I pick this as my favorite of the pre-Code musicals, though I couldn’t say a bad thing about Footlight or Dames if I had to.

Patricia Nolan-Hall · September 18, 2015 at 11:09 pm

“My Forgotten Man” never fails to leave me in tears. Powerful stuff.

During one of our viewings of this movie, the hubby turned to me and said “Poor you. Always had a thing for Warren William, but ended up married to Guy Kibbee.” Classic movies certainly do have a context in our real lives.

OK, if you say so, I’ll have to check out “Moonlight and Pretzels”.

By the way, great article!

Danny · January 8, 2016 at 12:02 am

Thanks Patty! Give your Kibbee a hug for me. 🙂

smumcounty · September 20, 2015 at 3:24 am

This is my favorite film of the pre-code era. I likewise was thrown by it, especially that ending. Great post.

Nitrate Diva · September 21, 2015 at 1:22 am

Wow, this is an amazingly rich, thorough discussing of a great film, and I’m really proud that it’s part of something I hosted. I love how you break up the film by musical numbers and examine the implications and wildly varying moods of each one. You really hit the nail on the head about “We’re in the Money,” which I’ve always found vaguely upsetting without being able to express why.

Finally, I totally agree that the legendary last musical number “comes closer to explaining this awful thing that the Depression was more than any cold statistical number or lengthy documentary could.” As you point out, the movie’s blend of fantasy and reality makes the sorrows of Depression feel so close and powerful even all those years later. Thank you so much for participating in the blogathon!

Danny · January 8, 2016 at 12:03 am

Thank you for finally getting me off my butt to review this one!

Lê · September 22, 2015 at 4:47 am

What a wonderful review, Danny! I was mesmerized about this movie. It’s heartfelt, it’s true, it’s raw sometimes. It is a complete image of the Depression era!

I learned to love Joan Blondell with this movie. Her “Forgotten Man” rendition gives me chills. And, indeed, the Shadow Waltz is hypnotic!

Don’t forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! 🙂

Cheers!

Le

Claudia Mastro · May 8, 2016 at 1:08 am

danny i love your site. i wish you could make a top ten of precode movies for each category (10 best romantic, 10 best dramas, 10 best comedy)

Danny · May 23, 2016 at 9:55 pm

Man, I wish I could too. :/ Too many movies to see yet!

Lucius Vanini · June 19, 2016 at 4:24 am

I recently saw a Hollywood movie about the battle between Welles and Hearst over CITIZEN KANE. In it Louella Parsons, depicted basically as a bad guy and therefore not recommended to the viewer’s respect, is asked what her favorite film is, and she answers GOLD DIGGERS OF 1933; and there’s a moment of silence and a look of dismay on the questioner’s face. Obviously we are being told that Parsons was a philistine, because look at what she accounts a great film!

I felt contempt, but not for her (assuming that GDs’33 was indeed her favorite film); I felt it for the joker who wrote the script thinking that Parsons could be derided for loving the Busby Berkeley classic. Said to myself, “She knew good pictures.”

I regard FOOTLIGHT PARADE (done the same year–can you believe it?!) as the greatest BB picture–indeed as one of the best pictures of all time; but GOLD DIGGERS OF 1933 is very fine too, as are 42ND STREET, WONDER BAR and DAMES, while the BB number “Spin a little web of dreams” is a magical oasis in a pretty arid FASHIONS OF 1934.

Brian Paige · April 3, 2018 at 8:24 pm

I too think of that scene from RKO 281 from time to time when I watch Gold Diggers of 1933. I think the point of it is to show that Welles is a film snob that would look down at a film such as GD of 33. He similarly disses Capra in the movie as well.

Lucius Vanini · April 4, 2018 at 7:24 am

Yeah, Brian, RKO 281 was the film. But was it Welles who asked the question? Now, I don’t remember Welles slighting Capra in the said film, but if he did I’d second him, because I’ve never had any use for Capra and his pollyanna pipe dreams.

As for GDs’33, it is as one expert has said, “the ultimate Depression musical,” and I think that the combination of good screenplay, great Hollywood players, Busby Berkeley genius, all crowned by that stupendous “My Forgotten Man”–a fearless and unambiguous political statement (unlike the oblique mind-conditioning of today’s Hollywood morality plays)–merits it a place in the top 100 Hollywood pictures of all time.

Christophe · December 20, 2016 at 12:04 am

Who is the lovely woman in the second photo of the gallery?

Lucius Vanini · November 30, 2017 at 1:35 pm

That was a Berkeley “chorine” whom I’ve never seen except in the “We’re in the Money” lineup (in which she is pictured here) and in the “Shuffle Off to Buffalo” train-car scene in 42ND STREET. I agree; she had a lovely face; but there were so many young beauties in the BB crowd competing to be seen, many of whose names I’ve ascertained through a little “detective” work and one of whom (Rosalie Roy: not in GOLD DIGGERS ’33, I believe, but in other BB films, especially FP where she’s seen most) inspired me to visit the little backwoodsy Arkansas village where she’s supposed to have grow up.

Will · November 22, 2017 at 10:50 am

Is that Theresa Harris in the photo of the African American couple in the gallery?

mjm · July 13, 2018 at 8:38 am

Yes, that’s her. Although the sight gag she’s a part of in that number smacks of racism (two chimps segueing to a black couple)

Comments are closed.