|

|

|

| Peter Standish Leslie Howard |

Helen Pettigrew Heather Angel |

Major Clinton Alan Mowbray |

| Released by Fox Film | Directed by Frank Lloyd |

||

Proof That It’s Pre-Code

- Look, a guy travels through time to bone his great something-or-other’s cousin. It raises questions, certainly.

Berkeley Square: Romance Through the Ages

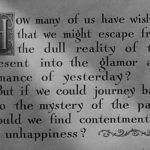

“Time– real time– is nothing but an idea in the mind of God.”

There’s a certain kind of person Berkeley Square is made for. That person is not me. Between the droning romantic platitudes and wry winking, it’s a quiet movie. Like waves on a beach on a calm day.

Peter Standish is two people, both played by Leslie Howard and separated from one another by a century and a half. In 1787, the early Standish is a Yank visiting England, judiciously being sure not to insult his hosts after their defeat in the American Revolutionary War. We’ll call him “Standish Prime”, just to make this seem more science fiction-y than it really is.

The other Standish, who inhabits contemporary 1933, is living in the same house that Standish Prime is due at in England, having just inherited it from a remote cousin. This Standish has found a treasure trove of artifacts linking him to the other Standish, including a painting that indicates even the personal appearance was identical. He becomes obsessed, shunning his fiance and keeping himself secluded until one afternoon where he consults with the American ambassador and confesses his intentions to switch places with Standish Prime.

With a lightning bolt, he opens the front door; the switch is sudden and complete. Suddenly he’s before Kate Pettigrew, Standish Prime’s betrothed. Standish is giddy, eager to live out his ancestor’s life by marrying Kate and living in a time where men where men and the air was clean. Well, besides all of the body odor.

Frankly, I imagine Howard dressed like this whenever I picture him mentally no matter the era his films are supposed to be set in.

Actually, the body odor turns out to be a sticking point, as Standish cries out “Lord, how the 18th century stinks!” A lot of things do, honestly, because Standish quickly discovers that you may be able to take the man out of the 20th century, but you can’t take it out of the man. He tosses off slang, reaches to shake hands with every person he meets, and generally can’t get past the casualness he’d grown accustomed to in 1933. He finds it amusing at first, but his manners combined with his ability to predict the future in a number of isolated moments begin to annoy and then terrify those around him. One snooty gentleman huffs, “We affect him as a tribe of barbarians would affect us!” before turning to gossip in horror that Standish is rumored to bathe every day.

“I feel like a fish out of water!” Standish cries. He’s imprisoned himself in the past, and his situation only grows more dire as he realizes that he’s not in love with Kate, but her younger, more ethereal sister, Helen.

The joke of the movie and the message is that it’s nice to want to go back to the past, but it’s just too damn foreign to us. I always look to the past as a vast dessert, with shapes buried under sand, grains rearranging as the winds of time conceal some things and finally reveal others. To presume you can step into that desolate mess is to invite disaster– what once you knew has shifted thanks to the tricks of memory. Standish, despite being a huge nerd who wants this with all of his might, just can’t escape what the 20th century has made of him.

It’s interesting to contrast the movie with its genetic cousin, Turn Back the Clock, which is a vastly different kind of film thanks to its Warner Bros. edge. Both are built around the personality of their stars– brashness in Lee Tracy’s case, playful romanticism from Howard. But where Turn is the story of a man learning his It’s A Wonderful Life lesson via a prickly bit of a pre-Code kick in the pants, Berkeley Square is more unnerving. Howard’s retreat into the past is a complete sublimation of himself, an attempt to prove himself worthy of the unknown past he desired so much as well as to dominate it with his knowledge and ways.

The humbling he gets out of it is much more devastating. Whereas Tracy lifts his head up and smiles, Howard holds the tattered remains of the only thing he’d connected to in his life’s dreams, separated by the void of time.

I’m going to get into spoilers here, so skip the next two paragraphs if you want to save the surprises. While flirting with light comedy most of its run, it takes a turn towards a romantic tragedy. Standish’s love for Helen allows her to see the world he’s from and the horrors of everything in between– war, death, and modernity of all stripes. But she realizes he can’t stay, even as they both understand that they’re the only two people in the world– in time– who understand each other. She’s promises that she’ll leave him a tribute to her love, engraved deeply on her tombstone that will stand the test of time. But when he returns to his present, Standish discovers she died shortly after his return, no message left. She was 21.

Helen’s young death would have been a tragedy if it had happened a year ago, but the extra decades compound it– she died young and beautiful and so long ago that no is left to remember her or regale Standish with her final days. He himself becomes the last testament to a woman completely alive and in his arms only a few moments ago– now separated by eternity.

Berkeley Square feels very stagey and very proper. Its 88-minutes long and feels it. Howard’s character is much of an enigma, lacking much in personality outside of his fascination with the past and his very real attitudes of the present. This is matched in the dialed-down direction, which is laid back and quiet. More than just stagey, it feels like one of those 1960s television productions where they’re obviously actors on an abstracted stage. The idea is to let your imagination do all of the work, but without the stylistic flourishes of those productions, it just compounds the falseness.

What I did appreciate is Howard’s growing, visceral anger with the people of the past that grows out of him. It’s his own snobbery on one hand, but, on the other, the film is firmly rooted in post-World War I trauma. With the men and women of the 1800s, it’s easy for him to growl at how these backward, smelly, and cruel people with their fancy airs. It’s their bad decisions that lead to all the terrible things that the future holds. Howard has a great breakdown as he can’t separate this from his ideals, oscillating between mocking his ancestors and screaming at them. His rant ends in angry defeat:

“What do I care about you? You’re all over and done with. You’re all dead, you’re all rotted in your graves, you’re all ghosts, that’s what you are, you’re ghosts!”

I wish we’d seen more of Standish Prime’s predicament, not the least of which because he spends the first few minutes of the film musing on the future. What we learn through dialogue is that he develops the same irascibility as his brethren, stomping about and refusing to leave the house after a series of humiliations and mistakes. That idea– that the future will revolt and isolate us no matter how wondrous its achievements– is something I can relate to more and more in an age of unending internet memes.

There’s a certain subset out there– people who can’t help staring at Howard’s pantaloons, perhaps, or those who are simply familiar with the more-contemporary Somewhere in Time or Midnight in Paris who can enjoy the gentle grooves of this film and the deep frustration that gnaws at the center of it. It’s interesting, but toothless.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- Remade in 1951 with Tyrone Power and Ann Blyth as I’ll Never Forget You.

- Gothic horror writer H.P. Lovecraft’s favorite movie. Maybe it’s the sinister swap between the two Howards that the movie makes a joke out of but seems so horrifying and strange to everyone else involved…

- Mordaunt Hall in the Times, still riding off the high of Lloyd’s Cavalcade, praises it heavily:

In the matter of poetic charm, nothing quite like it has emerged from Hollywood. It is an example of delicacy and restraint, a picture filled with gentle humor and appealing pathos. It is in a class by itself, which is not surprising, for Mr. Balderston had a hand in transforming the play into screen form and Frank Lloyd, who directed the memorable “Cavalcade,” officiated in the same capacity for this production. […] Mr. Howard revels in the role. He has done excellent work in other films, but it is doubtful whether he has ever given so impressive and imaginative a performance. He steps from modern attire to the clothes of the eighteenth century without any trace of awkwardness.

- The NYU Film Notes are great for this one, laying the blame at the feet of the lugubrious Frank Lloyd.

Rather appropriately, if accidentally, an anecdote from the cameraman of the film, Ernest Palmer (not nearly as well known as his superb photography entitles him to be) sums up one of the basic problems of the film. Having worked on early sound musicals, science-fiction films, and under such demanding masters as F.W. Murnau, he still feels that this film presented him with the greatest photographic problem he had ever faced. The script called for this specific image:

“A closed door which looks as though it is about to open”.

The italics are mine, but the problem was Balderston’s – and the film’s!

- A couple of stills and the Lux Theater adaptation of this one over at Doctor Macro.

- The Motion Pictures is far more into this one than me, and talks about why Howard’s acting work here is so lauded:

The potential for sci-fi cheese is also squashed by Howard’s understated performance, for which he secured an Oscar nomination. His face shines with the wonderment and excitement of the scenario, but he doesn’t go over-the-top, which increases the believability of the unbelievable situation at hand. The performances of the entire cast are solid, but with Howard’s star shining so bright here, there is little room for stand-out performances aside from his own.

- If that review sounded complimentary, TCMDB is practically throwing itself at the movie. Here’s their explanation for the very Britishness of this movie, as well as so many other movies of the pre-Code era:

Once sound came in Hollywood, and the distinction of voice and accent and therefore cultural evocations suddenly mattered, Hollywood became Little Britain. It was instantly assumed by the studio heads (which were mostly Eastern European emigres, who personally had no dog in the race, so to speak) that Americans didn’t want to hear any accent, not even a homegrown one, as much as a British one. Along with the (largely perceived) eloquence and authority of a refined Brit burr, then, Hollywood movies became intoxicated with all things British. Stage-trained British actors were hired where beautiful working-class schlubs from Dayton or Pittsburgh used to suffice, Brit plays and novels became prime projects, movies whose stories had no relation to England (think Animal Crackers [1930], Frankenstein [1932], Blonde Venus [1932], Top Hat [1935], etc.) were populated by officious British characters. Britishness itself was something of a prized quality, a nexus of signs indicating sophistication, credibility, glamour, and a sense of educated history, a useful hand of cards for any “crude and rude” American film save a screwball comedy to possess. Frank Lloyd’s Berkeley Square (1933) is both saturated in this uninterrogated idea of uber-Brit refinement and takes it slowly apart, excoriating itself and our lazy daydreams about the poshness and delicacy of life in the old Empire.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film plays occasionally on TCM, otherwise it’s pretty obscure. Good luck!

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar! |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Comments

Patricia Nolan-Hall (@CaftanWoman) · May 16, 2016 at 6:09 am

I prefer “I’ll Never Forget You” to this film, and a stage production I saw at the Shaw Festival a few years ago to both movies. Time travel stories intrigue me as I suppose that is part of what we do when we watch classic films.

Danny · May 23, 2016 at 9:59 pm

Well put.

nitrateglow · May 17, 2016 at 12:05 pm

I’m with you on the film, though TCM will play the heck outta it every now and then!

Camille · May 20, 2016 at 2:21 am

I’m with you too. I’ve always loved time travel stories, but this one is a real downer. The 1951 remake, with Tyrone Power, is no better.

Comments are closed.