|  |  |

| Manuela Hertha Thiel | Ilse Ellen Schwanneke | Frl. von Bernburg Dorothea Wieck |

Directed by: Leontine Sagan and Carl Froelich

Running time: 88 minutes

Proof That It’s a German Film

- Set in an all-girls school, some of the kids have girlfriends or get playful with one another, including slaps on the rear.

- A woman kisses a teenage girl on the mouth, lovingly, tenderly.

Girls in Uniform: A Little Love Lost

A quick disclaimer: normally on this site, we focus on film’s made in Hollywood from 1930 to 34, for the simple fact that it limits me to a manageable 2,500 films to cover. (Only 1,700 to go!) We’re also often focused on the plights of the American censors, producers and audiences, who were frequently at odds at one of the most volatile social eras of American history.

But, despite this being a German-made film touching on issues that would most certainly both irritate and titillate the American audience, the fact that Girls in Uniform did, remarkably, garner a nationwide release in the US is worthy of discussion. The film has a great deal to reveal about both the tail end of Germany’s Weimar film output and America’s fascination with European product.

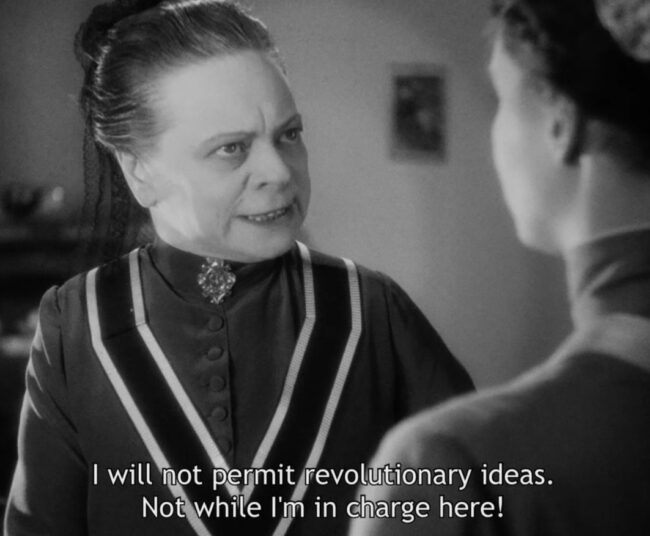

That front-loaded a lot of information and probably doesn’t make a lot of sense until you know the plot of Girls in Uniform. Set in an elite boarding school, we follow the delicate, orphaned Manuela (Thiel) as she makes friends and settles in under the repressive headmistress, Oberin des Stifts (Emilia Unda). The young ladies are trapped in hideous uniforms and make due with little food and a learning curriculum that focuses on punishment and humiliation.

Discipline throughout the film is tied deeply to nationalism– starving the students, terrorizing them, that is how we create good Germans. Well.

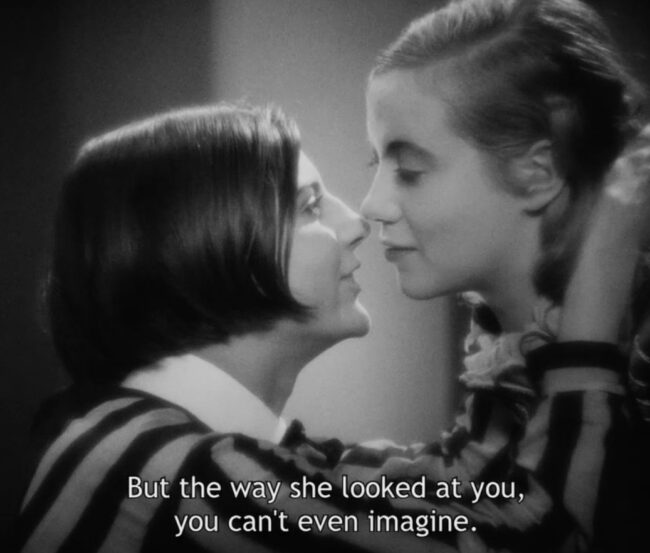

In this unpleasant hellscape, there is a bright spot for Manuela: one teacher, Fraulein von Bernburg (Wieck) is kind to the students, and many develop schoolgirl crushes on her. Manuela is instantly attached as a substitute mother-figure, and, perhaps, something more, evidenced by a nighttime kiss on the mouth and intense schoolroom fantasies on both ends.

Later, after a successful school play, Manuela gets drunk on a particularly powerful bowl of punch and announces to her classmates that von Bernburg and her are in love– she knows, because the teacher gave her a new pair of underpants and told her that she’ll think of her.

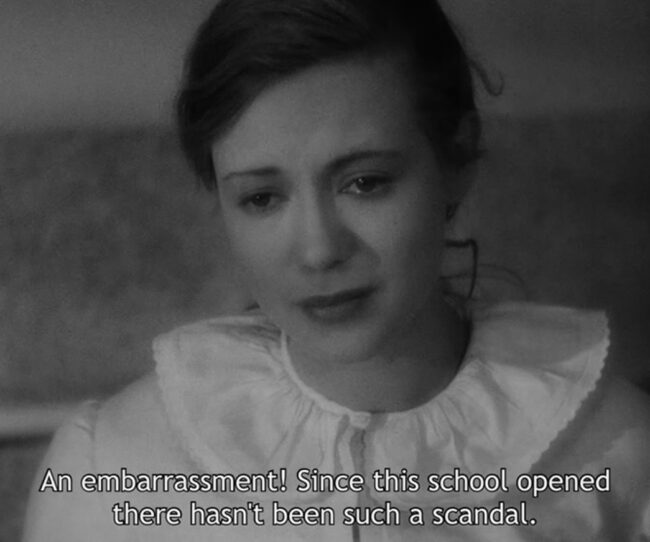

This certainly smacks of indiscretion, and when the headmistress overhears this proclamation, she unleashes her fury on the young girl. Manuela wakes up the next morning hung over, unsure of what happened, only knowing that her entire future is in doubt and now no one in her class will speak to her. She’s pushed over the edge when von Bernburg says that they must never speak again, and things take a turn towards the grim.

Given the events in Germany at the time, it’s impossible not to read things into Girls in Uniform. The way that good students are afraid to stand up and do anything. The way the staff craves power and domination with a weak hand. The way social norms are used to vilify and destroy the weakest. It’s both prescient, but also universal.

That being said, von Berburg’s display of ephebophilia (a word I know because the internet is fucking awful) is off-putting, giving off incestuous vibes that I’m not sure the film really knew what to do with. Film critic B. Ruby Rich, in her introduction on Turner Classic Movies, noted that this teacher/student relationship is a common fantasy for schoolgirls– as I’ve never been a schoolgirl, I feel awkward commenting on it. Other than to say that the movie’s treatment of it as an innocent romance of two beings of hope made me squirm a bit.

Girls in Uniform is beautifully and naturalistic in its look, often framing its characters with a wistful glow. The film was produced by a German collective, with a woman director at the helm, elevating its portrayals of a male-free space.

As a landmark portrayal of sapphic love, Girls in Uniform is a fascinating time capsule of German filmmaking, and its examination of fascism in the face of Nazism serves as a stark reminder of the ability of art to illuminate, both then and now.

Screen Capture Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- Remade in Germany in 1958 with Lilli Palmer and Romy Schneider.

- I was fascinated by the similarities and differences between Girls in Uniform and 1934’s Finishing School from RKO, which also featured a female co-director and a young, wayward girl getting an education at boarding school that lead to trouble. There are plenty of differences– unsurprisingly, the American version nixed lesbianism– but I thought the difference between the endings was the most stark. (Spoilers the rest of this bullet.) Girls in Uniform ends with the headmistress stalking away with horror and regret that her actions nearly caused a girl to kill herself. Meanwhile, the pregnant lead of Finishing School also almost kills herself before running off with her arrived-in-the-nick-of-time-beau, while that headmistress demands the girl come back and finish, essentially, killing herself out of shame. Must be a difference between German and American morality.

- Raquel Stetcher at TCM’s Tumblr talks about the film’s release– yes, it did play in America, thanks to an intervention often attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt.

Upon release, critics and audiences alike raved about the movie. It received glowing reviews. While it was never widely released in the United States, it did ultimately screen in over 1,000 theaters. Andre Sennwald of The New York Times called it a “masterpiece”. Mordaunt Hall of the same publication said in two 1932 reviews “Few motion pictures have been endowed with the magnetic quality of MADCHEN IN UNIFORM… It is a film in which all the characters fasten themselves in one’s mind, not as actors, but as real persons. The performances of all are deserving of the highest praise.” Of course the film met with some opposition. It was “Banned in Boston”, a badge of honor for provocative work. Film producer John Krimsky battled with the Hays Office to get the film approved for distribution.

Producer David O. Selznick was so impressed with Sagan’s debut film that he invited her to Hollywood. She made two films there, both were flops, and returned to the theater where she thrived. Actress Dorothea Wieck was also courted by Hollywood. Paramount executives, intrigued by her striking resemblance to MGM star Norma Shearer, put her under contract. Wieck’s Hollywood films were box-office failures. She was booted out of tinseltown and unfairly labeled a Nazi spy. The irony was that Wieck was an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime and refused to act in Nazi propaganda films.

- Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times reviewed this in 1932 after its premiere there. The last line in his review is telling:

It is a film which pleases the eye constantly, for one envisions not only the characters, but also their surroundings, whether they are in halls, rooms or in a garden. It is a production in which the background counts for much, and added to this aspect there are the players who are so well suited to their respective roles. It is not a film in which there is any evil intent, provided one analyzes the conditions of such students.

- DVD Beaver reviewed the latest blu-ray, with plenty of screen captures to explore.

- I can’t help but admire the sheer coldness of the contemporaneous Variety review, which is utterly cynical and notes:

New York’s picture critics threw their literary bonnets high in the air upon seeing this film, one of them even going so far as to call it the ‘year’s ten best pictures rolled into one’.All that may help in New York, for the first week or so of the film’s run, but after that, and outside of New York, the film will have to stand on it’s own as entertainment. And as entertainment it hasn’t a leg to stand on.

- The New York Times recently revisited this one because of its blu-ray release. They discuss the film’s afterlife:

Despite its international success, however, “Mädchen” was largely forgotten. Sagan, who was of Jewish descent, never directed another German movie. When, in 1952, the magazine Sight and Sound polled critics on the 10 Best Films of all time, the movie received a single vote (from an American, Archer Winsten, of The New York Post).

Before an influential appreciation written by the critic B. Ruby Rich in 1981, “Mädchen” was seen as either an expression of anti-fascism or lesbian coming-out film rather than both intertwined. […] Sagan’s film was both of and ahead of its time.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

More Pre-Code to Explore

1 Comment

Philipp · July 10, 2020 at 1:53 pm

As a German who sometimes reads your blog, this post is very interesting. We showed the film a while back in our student cinema group and it is such a quiet, austere yet powerful film which moved the viewers very deeply. And while the school in the film is not directly National-Socialistic but rather conservative and elitist, the school still embodies the Prussian morale of obidience and uniformity which made it so easy for the Nazis.

The Weimar Society had it’s friendly spaces for LGTB people, if one remembers Christopher Isherwood and his works. But “Mädchen in Uniform” is probably as openly lesbian as possible in the Weimar society. Christa Winsloe, who wrote the play the film is based on, was openly lesbian and died under tragic circumstances when she fled to France because of the Nazis and was thought to be a Nazi spy by the French resistance. Erika Mann, the lesbian author and daughter of Nobel Prize winner Thomas Mann, is also there in a supporting role as one of the teachers.

Similiarity to Hollywood films, the German films never reached that amount of openness about some themes until the 1960s came. There was no Hays Code, but there were the Nazi censorship and later the relatively conservative 1950s with mostly homely films. There is a 1958 remake of Mädchen in Uniform starring Romy Schneider and Lilli Palmer, which is better-known today (at least in Germany) because of the more famous leading actresses, but the remake is more shy and smooth about the homoerotic aspects in comparison to the older version.

Comments are closed.