|

|

|

| The Sergeant Victor McLaglen |

Sanders Boris Karloff |

Morelli Wallace Ford |

|

|

|

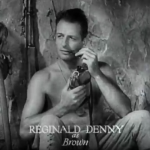

| Brown Reginald Denny |

Hale Billy Bevan |

Cook Alan Hale |

| Released by RKO | Directed By John Ford |

||

The Lost Patrol: An Oasis of Death

“We’re gravediggers now.”

“Out here? But where are we going to bury him?”

“Doesn’t make much difference, does it?

John Ford’s The Lost Patrol is a dizzying thriller, a virtuoso tale of death at the hands of an unseen enemy and a crackling metaphor for the disastrous British campaigns of greed and hubris of the first World War. It’s gorgeous, maddening, and thoroughly haunting.

Set during the campaign in Mesopotamia, a patrol of soldiers are marching through the dunes when the leading officer is shot and killed by a sniper’s bullet. The Sargent (McLaglen) is now stuck leading his troops out into the desert with no idea about their objective or their destination.

The group’s arrival at an oasis turns out to be a mixed blessing, for they now have food and water but are quickly robbed of their horses. With no way to summon reinforcements, the group first consoles themselves with stories of women and old glories– but then the sniper puts another of them in his scope and the pressure grows.

The shot of them arriving at the oasis, as foreboding and dangerous as you’d see in any horror film.

For a film with a pre-Code run time– barely 70 minutes– the film does a commendable job in acquainting the audience with the dozen or so men in the patrol. The gruff Sergeant who worries about getting too close to his men. The ponce rich kid who wants glory as he read about in Kipling. The pair of old regulars who argue with each other whose gotten in more trouble over their decades of service. The old vaudeville performer whose paying for his tragic mistake. The short tempered boxer. The suave man whose name isn’t his own. And the religious zealot who believes they’ve found the garden of Eden.

They’re all regular men, outcasts, sinners, and dedicated soldiers, all with a belief that they’re there for a reason, even if none of them, not even their commander, knows it. That’s a feeling that’s highly reflective of the first world war in general, as are many of their fates.

Another one bites the dust.

Spoilers.

The gleam off the sniper’s rifle is the only thing that most of the men see before they die, if that. The sand dunes that surround the oasis serve as a metaphorical trench which they peak their heads above. One by one the men make themselves targets, either by venturing into the no man’s land of the stretching sand dunes or by sitting too high and seeing the distant outline of a gun pointed at their head. Their misadventures grow as madness and fear take over. One crosses the threshold in the heat of delusion, another trumpeting revenge.

A few endure longer than the others. One of the more notable is Sanders, a meek zealot who chastises the others for their unholy attitudes and behaviors. Karloff plays Sanders with the same fanatical devotion as his Poelzig in The Black Cat, but he also imbues in him a sliminess that repels the more agnostic around him.

Some movies would make him the savior or merely a hypocrite. Here he’s merely another symptom, bringing with him the baggage of centuries of crusades and holy quests. As his comrades come closer to the grip of death, he channels their loathing of him into his persecution complex. He views himself the same as Christ, a savior. His final act is to rid himself of his uniform and dress himself in rags, prepared to talk to their Arab enemies not as a soldier but as a messiah. Unsurprisingly, they want none of that.

Oh, this always ends well.

Wallace Ford’s Morelli, a former vaudevillian, is another interesting examination of enduring under great pressure. The performance is fine– Ford wisely loses the goofy Irish accent after his first few scenes– but it’s his panicky unraveling that really reflects the group’s disintegration. After two men who had left to get help are sent back by the Arabs tied to horses dead, naked, and with unmistakable grimaces of horror on their faces, Morelli loses his ability to block it out.

He cracks under pressure. The unshakable jokester reveals his sad story to the Sergeant, about how his last act crippled his wife out of his own unabashed egotistical drive. Like many before him, he joined the army to escape his problems. He’s just in a new, unfathomable one now, something that hundreds of performances couldn’t get him ready for.

There’s a genuine sense of decency that Morelli has that’s missing from Reginald Denny’s character, Brown. Though the youngest of the soldiers exalts him as a hero, he’s a ruffian from way back, with a past of sins that he would rather leave out. Brown seems like the usual kind of hero in a story like this, which is why his end is so remarkable. He too decides to venture into the desert at night to face their opponent, leaving behind only a note for the Sergeant to read. His off-screen death for such a featured character is a shock.

Ouch, glad I ain’t that guy.

As a narrative conceit it’s interesting– possibly setting him up for a hero’s return later, but that never happens. Whether it’s more cowardly to meet death in the middle of the night alone or to wait with your compatriots and stick it out together is an interesting dilemma, but for the type of person that Brown was– sly but practical– he knows that in his case, at least no other soldier will be fool enough to run after him when he dies this way. It’s almost noble.

The whole film, though, revolves around Victor McLaglen’s Sergeant, trapped between duty, necessity, and the unseen enemies surrounding them. As he sees more of his command perish, as his options dwindle, as escape literally lands in front of him but he’s unable to do anything to save it, his will and gruff exterior melts. Unlike Morelli, he remains defiant, but he lacks the ability to out think his foe. He is unwilling to pick the men to sacrifice or make difficult decisions. He’s the default leader, but unprepared for the situation. Not that anyone else would be.

The film’s ending is almost Buddhist in its conclusion… well, maybe moreso if it weren’t for the gunfire. With his last men cut down, the Sargent buries them and digs his own grave. He puts on his dress uniform, gathers his weapons, and lays down. Only by playing dead do the Arabic pursuers finally show themselves, though they remain faceless even after they arrive. The Sergeant’s desperate machine gunning finishes off the attackers, and he laughs merrily, proudly and maniacally boasting to the graves of his friends about their triumph.

Ford briefly breaks the fourth wall a few times, though never as memorably as this triumphant dance by the Sergeant as he is flushed with victory.

The film’s final few moments, of the support battalion’s arrival and the Sergeant’s inability to explain where his patrol is– only able to point to the row of swords used as grave markers– is capped by a perfect finale. Rather than explanation, condemnation or sorrow, Ford cuts here and leaps to the battalions departure from the oasis, marching away while the camera remains enmeshed in the sinister trees of the oasis. The distant strains of a song honoring the queen fade off while we, the audience, are left behind, one of the unfortunate– and lucky– dead.

End spoilers.

Cinematographer Harold Wenstrom (The Big House, The Secret Six, and, inexplicably, What– No Beer?) works together with Ford to give the film a beautiful, evocative feel of isolation and creeping danger. The miles of sand dunes and windy weather create a memorable set piece, a bite-sized paradise that remains, as one character notes, ‘the devil’s own backyard’.

The Lost Patrol is a great anti-war film, an ode to the millions of men who have died without reason and a warning to those who watch. It’s the British lower class’s valiant attempts to survive complete incompetence at the top, a doomed campaign in a war of aggression derived from calculated hubris and greed.

Gallery

Hover over for controls.

Trivia & Links

- This is a remake of a 1929 film of the same name which starred Victor McLaglen’s brother, Cyril. Ironically, that version of the film is considered lost.

- Eagle eyed viewers may recognize some of the scenes here being reused in more famous films– Akira Kurosawa mimicked the film’s final shots in Seven Samurai (1954), and Ford himself reused one character’s death scene at the top of a hill in his later film The Searchers (1956).

- Eagle eared listeners may recognize the score from this film from Max Steiner, with some of the themes here being switched up and the tempo modified to be reused in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and Casablanca (1942).

Ford does a great job in the first half showing the connection between the soldiers and their horses. When he removes that at the end of the first act, it’s not just crucial to the plot, but an emotional loss as well.

- History on Film is pretty handy with the historical context for the movie, including information about English and Turks fighting over Mesopotamia in the war and background on some of the soldier’s motivations. A good read.

- Greenbriar Picture Show discusses the film’s history after its filming, and how its print length has evolved over the years, from edits to cut its length down to put into a double feature or how it was cut for television, creating a situation where for decades nearly ten minutes of the movie were considered lost. He also talks about how much money John Ford made off this picture (the answer: tons).

- Tons of posters and stills over at Dr. Macro.

Another inglorious end in a forgotten conflict in which nothing was gained by anyone but the reaper.

- I don’t normally link Cinepassion since it’s usually dry recitation of plot points, but he really does a beautiful job of summing up the film and capturing its aura. A highlight:

Despite Max Steiner’s bagpipes and bugles insisting on blessing the Queen, Ford complicates the plot’s jingoism — McLaglen’s climactic machine-gun ejaculations aren’t an officer’s fierce triumph, but a dead man’s scabrous spasms.

- Some old NYU screening notes by Richard Kraft gush about the film (scroll to the second page), along with this nice observation:

In conclusion, let me merely say that I love this film; but I am conscious that there are many who hate it for the same reasons that I esteem it. It is not a picture that one likes mildly. To me it is the essence of the real Ford, and a study of true heroism – the inner kind, not the last reel cavalry charge to Glorious Victory.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film appeared in the Wikipedia List of Pre-Code Films.

- This film is available in the John Ford Collection, which is available over at Amazon. As of this writing, it’s also streaming on Warner Archive, where the screenshots for this review are sourced from.

|

Comment below or join our email subscription list on the sidebar!Home | All of Our Reviews | What is Pre-Code? |

8 Comments

Gretchen Young · March 28, 2014 at 5:14 pm

always liked the “proof that its a pre-code” section which is sadly missing today.

Danny · March 28, 2014 at 9:26 pm

It was actually there earlier in the day, but there was only one item in it– one guy talks about how his wife had a kid surprisingly soon after them getting married. It really wasn’t that good of an aside, and I thought the review was stronger without it. Don’t worry, this is the first (and probably only) time I’ve ever done it.

shadowsandsatin · April 1, 2014 at 10:37 pm

This is totally not my kind of movie, Danny, and I have never heard of it, but your descriptions of the fully realized characters kinda makes me want to check it out!

Danny · April 2, 2014 at 5:13 pm

Ha! Yeah, I don’t know if it’s really up your alley either, but it is really solid. If you run into it along your journeys, I hope you enjoy it!

justjack · April 3, 2014 at 10:21 am

It’s really, really good, and Victor McLaglen is terrific in a role that’s worlds away from the kind of Sergeant he would later play in Ford’s Cavalry trilogy. That said, the real revelation is Karloff. What a spooky sumbitch.

I also love how the movie plays with your expectations, and every time things start to look up, the rug gets pulled out from under the men, and by the end, they’re doing it to themselves. It can emotionally exhaust the viewer!

Finally, Danny, I note your screencap of the patrol arriving at the oasis, and it suddenly occurs to me that this is in fact an example of a signature Ford visual touch (I learned about it from The Searchers’ audio commentary track). The foreground will be quite dark and claustrophobic, and frames an opening through which we can see out into an expansive, bright exterior. The best example I guess is the final shot of The Searchers. But Ford used it a lot.

It never occurred to me until now to compare the final pan over the graves in The Lost Patrol and Seven Samurai. Thank you, Danny, for pointing that out.

Danny · April 4, 2014 at 3:46 pm

It’s not just that the rug gets pulled out from under the men, but that it’s so brutal and so sudden. They never have a fighting chance but can’t admit that to themselves.

Thanks for the point about The Searchers commentary. I actually haven’t seen that movie since high school (AKA the turn of the millennium) so I definitely owe it a rewatch.

Bill Gedeon · April 22, 2014 at 6:55 am

“Filthy drunkenness and brawling..Why Brown, you have breeding”…

Comments are closed.