|

|

|

| Vivienne Ware Joan Bennett |

John Sutherland Donald Cook |

Dolores Divine Lilian Bond |

| Released by Fox Directed by William K. Howard Run time: 56 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- “What I sucker I was. I thought that sugar daddy meant he was going to take me abroad for a trip to France.”

“Yeah, where’d you get that idea?”

“‘Cause he told me someday he’d show me the place where he was wounded during the war!”

- One of the film’s character always has “room for overnight guests at his house”. He is described as “boudoir-conscience”, and viewed all women as “guilty until proved innocent.”

- Dolores Divine (Bond) has her pajamas described as “suggestive”– “while revealing everything, they seemed to suggest so much of nothing.”

- Two women are turned on by the voice of radio announcer Graham McNally. “[T]he power of it– it just rouses within me everything. … uh, maternal.”

- The mechanic is enjoying his evening by drinking some near beer.

- The film’s nightclub has an act referred to as “the Adam and Eve number.”

- There’s almost a gay slur, which is weird!

“Did you pick up any fares that night?”

“Any what?”

“Fares.”

“Oh, I thought you said fa– heh.”

The Trial of Vivienne Ware: No Recesses

“Now put on your bonnet. We’re all going to take a little ride.”

When asks you for a specific pre-Code that is “fast-paced and snappy”, The Trial of Vivienne Ware may be a good patient zero to refer to. Directed breathlessly, the 55-minute film zips from scene to scene, a deliberate tempo that never lets up for a second.

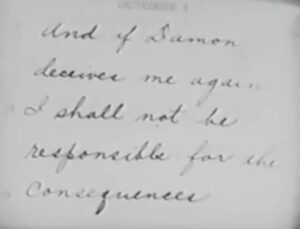

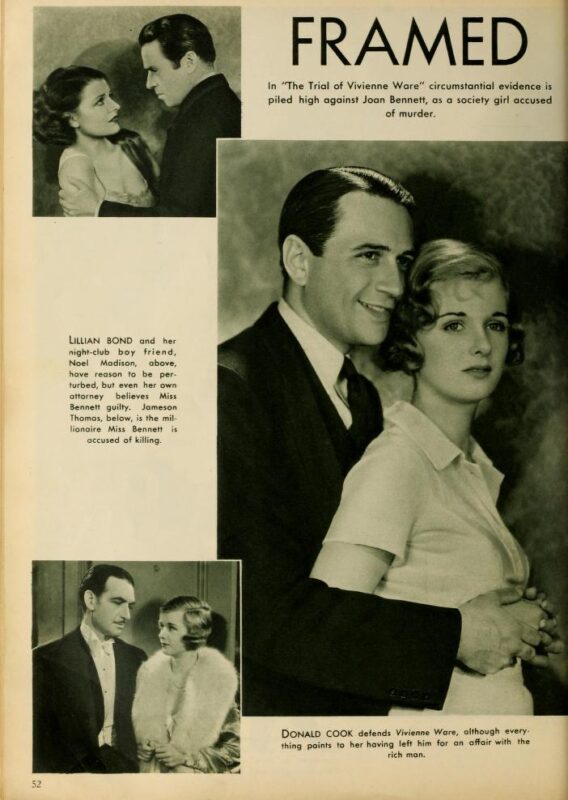

Vivienne Ware (Bennett) is on the top of the world, happy to be engaged to rich and debonair Damon Fenwick (Jameson Thomas). However, he secretly has a lover, the singer Dolores Divine (Lilian Bond), while Vivienne has the moon-eyed lawyer John Sutherland (Cook)tagging along. Nightclub owner Paroni (Noel Madison) also has a stake in things. We see a few people come and go and Vivienne quickly packing her bags and suddenly she’s on trial for murder.

A variety of colorful witnesses are brought on, including Fenwick’s butler Boggs (Herbert Mundin), nosy neighbor Elizabeth Hardy (Maude Eburne), car mechanic Axel Nordstrum (Christian Rub), and Ms. Divine herself– who almost gets murdered on the witness stand by shady figure throwing a knife.

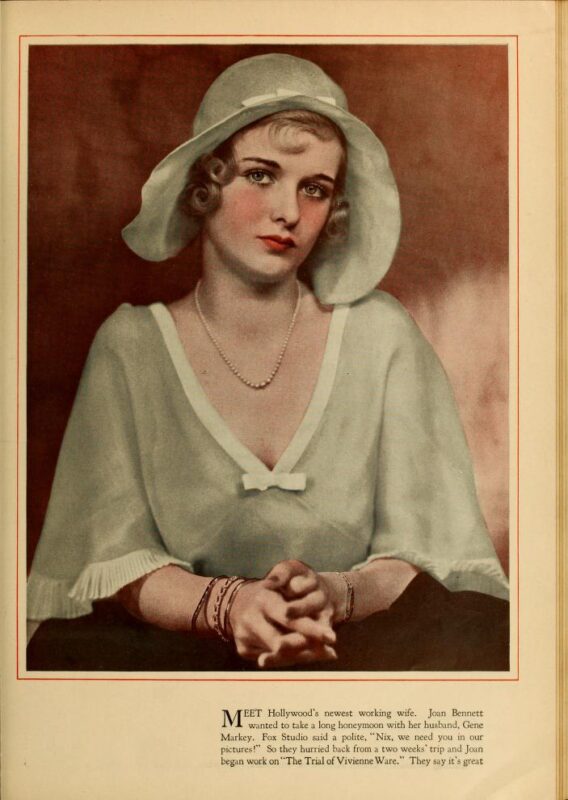

Several characters descend on the trial, eager to cash-in. This includes radio announcer Graham McNally (Skeets Gallagher) and a reporter ‘on the female angle’ Gladys Fairweather (Zasu Pitts). Fairweather gleefully describes Vivienne’s fashion day-in and out and even manages to land a jailhouse interview with her, wherein she attempts to mimic being a Virginian to get on Vivienne’s good side.

The trial is pretty enjoyable, unrestrained by logic, sanity, and most definitely not the actual legal customs of our country. Quick-paced editing and whip pan dissolves push the movie along at a breakneck pace. The various media commentators are on hand to rat-a-tat-tat some exposition so we’re not slowed down by actual dialogue. “She’s on a trial for her life!” Gallagher will shout into the microphone as it swooshes back to the courtroom. Zasu will try and insert something about the symbolism of her dress color and again off we go.

The editing and pace are the stars of the picture, moreso than poor Bennett who must simply look concerned throughout. The hyper-saturated pace and the integration of media commenting on every aspect of the proceedings actually give the film a rather modern feeling; you get the news all the time, whether you like it or not, and everything becomes a kind of a frantic blur.

While the mystery itself isn’t very dense, but it moves so fast that you can hardly keep track of exactly what is happening and why. And I was pleasantly surprised by the murderer’s identity, I will admit. The Trial of Vivienne Ware is a unique, freewheeling film that’s worth spending an hour with.

Screen Capture Gallery

Click to enlarge and browse. Please feel free to reuse with credit!

Other Reviews, Trivia, and Links

- So the genesis of this film is pretty crazy. Here’s the Wisconsin Cinematheque talking about the original inspiration for the film:

The script for this program had been heavily influenced by an American true-crime story— the Thaw-White trial of 1906. Harry Kendall Thaw was the son and heir to the fortune of Pittsburgh coal and railroad baron William Thaw, Sr. On June 25, 1906, on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden, Thaw murdered renowned architect Stanford White, who had sexually assaulted Thaw’s wife, model/chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit. The trial is notable for the proliferation of yellow journalism and sensationalist reporting surrounding the case, which was met with counter arguments by the wealthy Thaw publicity machine. Indeed, only one week after the murder, a nickelodeon film, Rooftop Murder, was released, rushed into production by Thomas Edison. After one hung jury, Harry Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity. Later, the Thaw-White case was worked into the historical tapestry of E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime and the 1981 Milos Forman film adaptation. The trial also inspired the 1956 Fox movie, The Girl on the Red Velvet Swing, and the story was modernized by Claude Chabrol for his French drama, A Girl Cut in Two (2008).

- If the origin for the story isn’t crazy enough, here’s the permutations it took before it got on the screen via the AFI:

The novel by Kenneth M. Ellis originally appeared in serial form in the New York American newspaper during the time period in which the radio drama of the same name was broadcast over New York station WJZ. According to an article in Radio Digest, in October 1930, Edmund D. Coblentz, the editor of New York American, read about the broadcast of a murder trial in Copenhagen and got the idea to sponsor a fictional murder trial that would be broadcast in New York over the radio. He assigned Ellis, a feature writer for the newspaper, to write the story and arranged with WJZ of the NBC network to broadcast the trial on six successive nights. The circulation department of the paper offered money prizes for the best verdicts that listeners sent in. U.S. Senator Robert F. Wagner from New York played the judge in the broadcast, while internationally famous lawyer George Gordon Battle and former Assistant District Attorney of New York Ferdinand Pecora played the lawyers.

The play was subsequently broadcast in other cities where Hearst newspapers were published. A sequel, entitled Dolores Divine, Guilty or Innocent, which was also written by Ellis and published first serially in the New York American and then in book form (New York, 1931), also attracted famous legal names to participate in the cast, including ex-Governor of New York, Charles Whitman and former New York Supreme Court Justice Jeremiah T. Mahoney. According to information in the Twentieth Century-Fox Records of the Legal Department at the UCLA Theater Arts Library, the writers of the screenplay read both books before starting work on a treatment, and they were unable to state how much of either was used in the final film, which credits only the earlier novel.

- Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times scoffs at this one, noting about the legal theatrics here, “the tactics employed are such that they make the liberties taken in other productions seem relatively restrained.”

- Francis M. Nevins at Mystery*File compares this film to how Erle Stanley Garnder wrote his similarly fast-paced Perry Mason mysteries.

- Just on the off-chance you’re looking for film like this one, this movie really made me want to watch Fog Over Frisco again.

- Some publicity pages from Photoplay and Picture Play.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This is a Fox Film, and thus pretty obscure. As of this writing, it is on YouTube in a not-so-great print.

More Pre-Code to Explore

|

|

|

|

|

|