|

|

|

| Madeline / Shanghai Lily Marlene Dietrich |

Doctor Harvey Clive Brook |

Hui Fei Anna May Wong |

|

|

|

| Henry Chang Warner Oland |

Sam Salt Eugene Pallatte |

Mr. Carmichael Lawrence Grant |

| Released by Paramount Pictures | Directed by Josef Von Sternberg Run time: 83 minutes |

||

Proof That It’s a Pre-Code Film

- This film’s most infamous line is a doozy, especially as Marlene Dietrich coos it with a mix of anger and seduction:

“It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.”

- Both Madeline and Hui Fei are that kind of woman. As one of the train passengers notes dismay, “One of them is yellow and the other of them is white, but both their souls are rotten!”

- Rape and murder, plus all that other stuff listed in the tags above.

Shanghai Express: Night Train to the End

“You’re right. Love without faith is like religion without faith– it doesn’t amount to very much.”

Sometimes I try and imagine a modern world where something like Shanghai Express could be the highest grossing movie of the year. It’s film that’s moody and deftly staccato– despite a romance that lines the proceedings, it’s treated with gruff distance and the audience is left floating on the smoky in-between. This isn’t a great romance, it’s the story of survival in hell, a Faustian tale of passion where every clasp of a hand to another’s shoulder has the unmissable stench of desperation. It’s a dispatch from a world gone mad, and even though the Depression doesn’t even get a murmur in the dialogue, the aura is so pervasive that the movie feels almost untranslatable to modern sensibilities. If you think this ugly world is bad, remember– back then, this was escapism.

We follow a group of first class passengers on their three-day train trip from Peking to Shanghai; they’re eclectic to say the least. There’s the quiet, grumpy German man who is fussy about the air he gets. The French colonel who speaks only, well, French. There’s an American gambler who can’t help but lay odds on every little complication that arises, and an older woman who owns a high-end boarding house and looks down her nose at the rest. They match well with the American missionary who grumbles at the heathens who surround him. There’s a mysterious Chinese woman, and a half Chinese man named Chang who looks at everyone a bit too long. The cynical, unattached Brit Dr. Harvey, has a stiff upper lip that seems to have been frozen there for centuries. And then there’s Madeline, now known as Shanghai Lily– a German woman who has seen everything, always with the same coquettish grin etched on her face and a flicker of mischief in her eyes.

The trip is through crowded, tumultuous China, beset by bandits and civil war. The Western-friendly government is pretty useless and the sight of men being killed hardly causes an flicker for the passengers— they’ll see a lot of dead native men and women before this voyage is over. As Chang notes ominously near the beginning, “You’re in China now, sir, where time and life have no value.”

Their whiteness protects them, at least for the “real” whites among them. The passengers, almost all Euro-American in descent, represent much of the worst of the outside plagues upon China. The missionaries who attempt reform through sheer condescension, the gamblers who engage others in their degenerate hobbies, the wealthy land owners who look down anyone outside the finest of fine circles, the man who claims to be kindly gentry but instead deals opium, and the military officer who obeys orders rather than thinks about them.

Chang is different. He’s half-Chinese, half-white, which the gambler, Sam (Pallatte) grills him about. The whispy Chang (Oland) solemnly explains that he is not proud of his white half, which Sam responds with his usual brainless gusto (and love of drink), “What future is there in bein’ a Chinaman? You’re born, eat your way through a handful of rice, and you die. What a country! Let’s have a drink!” But it’s easy for the audience to understand Chang’s position: most of the whites, save for Lily and possibly Henry, share Sam’s contempt for the country they reside in. These people are completely unwilling to engage in anything but encouraging their individual governments to fund the Chinese ruling class who persecute and terrify their countrymen mercilessly, whenever they’re not just completely incompetent. That Chang turns out to be a rebel isn’t much of a shock, and what he does to the men who insult him and his country is gruesome to say the least.

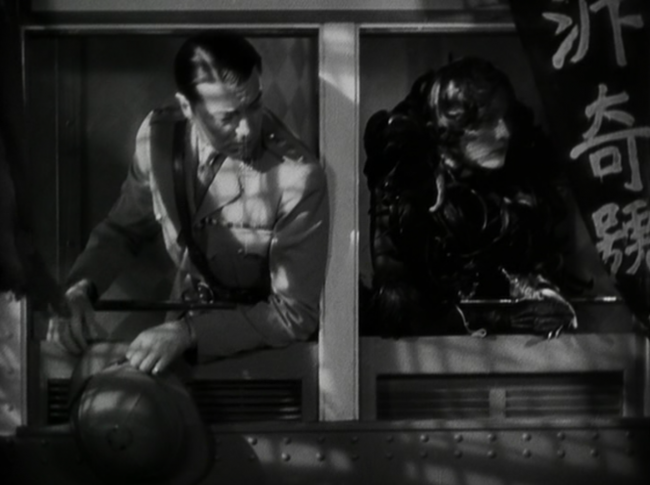

Lily and Harvey were once lovers years ago. The two reunite on the train in one of the best sequences of the type you’ll see. Both are leaning out the window and only registering the most marginal of emotions, the past teased at. Clive Brook, upon seeing the woman he’s counted the years since he’s been near, barely hints at an emotion. He’s so dead inside, there’s nothing. Lily has a harder time hiding her delight. As the two banter about their past, they lean in and out of the train, the two window frames separating them like cartoon panels. von Sternberg’s camera slips inside the train car only momentarily to reinforce the charade the two people are playing, those competing senses of desire and resentment that are furiously waltzing.

Here’s some shots of the scene. Even without the dialogue, you can read the emotional cues so easily:

Their love story serves as the backbone for the adventure– the two had separated over a matter of trust, and it’s now time for a second go at it as Chang’s rebel force captures the train and holds Henry hostage in exchange for one of their own spies. Madeline offers herself to Chang to save him, but not until Hui Fei has already been raped by his greedy, power hungry hands.

Anna May Wong who– thanks to blatant and frankly sickening racism on the part of both studios and the public– had once been a silent star, saw her fortunes decline precipitously in the talkie era. She shimmers here, and clearly has the screen presence to match Dietrich– no easy feat, especially in a film directed by Dietrich’s then-lover. Her character of Hui Fei is composed entirely of ellipses, the unknown known who smiles more at her solitaire cards than at any of the other passengers.

Save for Madeline. What is their relationship? Did they know each other before the train ride? Or are they just two women who have been around the block and respect that in one another? Or was Carmichael’s loud insistence of Hui Fei’s shady past an error, a man blinded by his own brand of racism that he presumed the worst? Whatever the course of the matter is, the most (and most telling thing) we learn about Hui Fei comes from the dagger she keeps in her bag. She knows when to keep quiet, and she knows when to strike. Wong’s ability to balance a quiet anger, distant amusement, and sheer bravado is nothing short of fantastic.

That makes Fei a perfect match– if not friend, then companion at the very least– for the utterly capricious Madeline. Madeline was wounded in one lover’s inability to trust her and has spent years cultivating distrust with the due respect of a diligent farmer. Dietrich is quiet as Madeline– assuredly quieter than you probably will remember– as she prefers to hook the unsuspecting with her soft teases and lower their guard as they get closer. That hides her real power, too– she wrestles a gun away from someone at one point and is more than willing to kill for the man she deep down loves.

In this way, the way the two women are connected together in temporary but complicit friendship is as uncanny of a commentary as the subtle digs at white egotism. When a woman lowers her status, her agency is removed. You can justify any of your actions towards a woman– from mistrust to rape– if you see her as free and easy. They’re shameful, antiquated feelings, built alongside the bigotry that led Europeans to create the then-disastrous, murderous Chinese state of colonial fiefdoms. Only respect and understanding can save anyone from their own awful attitudes.

No one is happy in Shanghai Express, save for those too stupid to know any better. A few learn something from the experience, although I think the term ‘grudgingly’ can be liberally applied here. The preacher learns prostitutes have souls. Hui Fei learns revenge can feel satisfying but will bring the harsh light of the public upon it. And Henry finally learns to trust without proof– a feeling of generosity unmatched by any other character in the film save Madeline. And while they kiss in the crowded train depot, there’s a small redemption among the chaos– a brief moment of real humanity.

Like a lot of pre-Code von Sternberg, the prices paid for this moment are almost too much, but he fights the right balance in his disdain and hopeful tendencies this go around. The movie is drenched with atmosphere, shadows layering the Chinese fog. The smoke curling off of Marlene Dietrich’s lips is evocatively wistful, while the costume design from Travis Banton is a stunning mix of ornate and chaotic.

Shanghai Express is a pristine product, one of the most stylish movies of the early 1930s from one of the most glamorous and daring studios starring one of the most beautiful actresses at the height of her charm and corralled by one of the most innovative directors at the time. It’s no wonder it was a success– it’s a challenging but exciting film, one that both pushes and teases its audience while heaping upon them visual extravagance. Through Dietrich, it captures the last vestiges of European mystique before Hitler’s rise and the trudge of Depression would erase them almost-permanently, an exotic allure that mixes class and desperation in one succinct, poetic package. They don’t make movies like this any more– they simply couldn’t if they wanted to.

Gallery

Click to enlarge. All of my images are taken by me at full screen size– please feel free to reuse with due credit!

Trivia & Links

- The TCM/Universal issued DVD (a result, I have little doubt, of TCM breaking into the Universal vaults and spiriting off with the negative while the guard was asleep) has a good selection of images related to the film as bonus features. This includes lots of the striking cubist image of Dietrich used in much of the poster art, which you can also check out over at Doctor Macro.

- TCMDB goes into the making of this film:

From the beginning of their collaboration, von Sternberg and Dietrich had been having an affair, although both were married. Von Sternberg was clearly in control behind the camera, but increasingly, it appeared that Dietrich, with her non-exclusive attitude toward sex, had the upper hand in the romance. She indulged in affairs with Gary Cooper and Maurice Chevalier, then went back to Germany to see her husband and daughter. Von Sternberg was feeling both personally and professionally frustrated, and wanted to abandon the partnership. Critics, too, were beginning to grumble that perhaps the Dietrich-von Sternberg films were too rarefied, that the exotic German beauty might do well to work with another director. Dietrich, however, would not work with anyone but von Sternberg, and he began preparing Shanghai Express. Shortly before the film went into production, von Sternberg’s estranged wife sued Dietrich for alienation of affections and the suit was later dropped.

Given the tense circumstances, and von Sternberg’s tyrannical manner and mania for perfection, working on Shanghai Express was a stressful experience for everyone. Von Sternberg shouted so much that he lost his voice. A production executive gave him a microphone to use, and von Sternberg went one better and hooked up a huge public address system, so his voice boomed in all corners of the soundstage. Cinematographer Lee Garmes recalled that the director acted out all the roles and insisted the actors imitate him. “His impersonation of Anna May Wong had us all in stitches. But we didn’t dare show our amusement.”

- The Picture Show Man has a full biography of Anna May Wong for your pleasure.

- Greenbriar Picture Show talks about the long periods of unavailability of this film and why it’s the best of the Sternberg/Dietrcih combos:

Shanghai Express is probably the half-dozen [Sternberg-Dietrich collaborations] best bet for sharing. There’s stronger narrative than usual for Sternberg, which maybe accounts for revenue earned in 1932 — $827K in domestic rentals and $698,000 foreign against a negative cost of $851K. You could say Dietrich peaked with Shanghai. Her vogue (at least the first one) didn’t last so long. Books/trades suggest Para offered her as ready-made successor to Garbo, stardom a fait accompli. The company’s promoting strength was equal, if not better, than Metro’s. Did Paramount simply dust off blueprints from their Pola Negri build-up to launch Dietrich? There was an industry ball to introduce the new personality just off a boat from Germany. That room filled with Hollywoodites went numb at the sight of MD, so witnesses say. I wonder what crumbs of truth, if any, are in that …

- Angela at the Hollywood Revue notes:

It’s a wonderful movie and is the ultimate example of what an expert von Sternberg was at making Marlene look utterly fabulous. The cinematography is exquisite and Shanghai Lily is easily the most spectacularly dressed traveler I have ever seen.

- Kristina at Speakeasy talks about the film’s beautiful look and Dietrich’s sublime performance:

There is loads of atmosphere, from the moment the detailed Peking station set is graced with the arrival of Dietrich, sleek and mysterious in black lace, silk and feathers courtesy of designer Travis Banton. The Oscar-winning cinematography by Lee Garmes (with an uncredited James Wong Howe) richly captures contours and textures. Sheers and shades are pulled every which way as figures in silhouette attempt forbidden acts, seek secrecy and commit murder. Dietrich is ultra-glam and intense, all cheekbones and a knowing smile. Her eyes dart to and fro like pinballs at times, as if great effort is needed to maintain her facade in front of Brook, the one man who knew her “before.” But she more than makes up for mannerisms when her flippant, deceptive front finally crumbles to show genuine heartbreak at the loss of Brook’s trust and love.

- And, yes, Lady Eve has even more about the film’s fashion. Lots about Travis Banton here.

This ensemble was concocted, according to Dietrich’s daughter Maria Riva, by her mother and Travis Banton. She writes of Dietrich going to the studio and running into Banton’s private office shouting, “Feathers! Travis – feathers! What do you think…Black feathers! Now, what bird has black feathers that will photograph?” The black-green tail feathers of Mexican fighting cocks were eventually chosen. Selecting the proper veil fabric took as long. Riva reports that when Dietrich finally held up a swatch of “black 41” with its horizontal lines, “Travis let out a wild whoop.” Finally, von Sternberg came to take a look at the completed outfit. There had been concern about his reaction – the elaborate costume would be very difficult to photograph. In German he said to Dietrich, “If you believe I am skilled enough to know how to photograph this, then all I can offer you is – to do the impossible.” In English he said to Banton, “A superb execution of an impossible design, I congratulate you all.” After the director left, Banton broke out a bottle of champagne.

Awards, Accolades & Availability

- This film is available on DVD at Amazon thanks to TCM. There will (hopefully) be a blu-ray of it available soon as well.

More Pre-Code to Explore

13 Comments

Devon Rains · April 8, 2016 at 1:32 am

For some reason, I’ve avoided much of Marlene Dietrich over the years – too many bad impressions led me to believe the real thing was just as campy. But reading this make me desperately want to see this film. She is striking, and Anna May Wong is fascinating. Maybe tonight!!

Danny · April 13, 2016 at 2:35 pm

Dooooo it!

Anthony Crnkovich · April 8, 2016 at 1:38 am

Excellent, spot-on review of this extraordinary, multi-layered film. When it comes to the von Sternberg/Dietrich cinematic canon, few films come close in terms of sheer, individual style; from narrative and performance to photography and costumes, all of it dazzles with aesthetic flair.

Danny · April 13, 2016 at 3:03 pm

I’ll admit I still tilt towards Blonde Venus (so far, have a few left to do), but this is an excellent piece of work.

Mark A. Vieira · April 8, 2016 at 4:00 am

This is not true: “The TCM/Universal issued DVD (a result, I have little doubt, of TCM breaking into the Universal vaults and spiriting off with the negative while the guard was asleep).” Universal has an established release program. You should consult the parties you are mentioning before you make baseless statements.

Danny · April 13, 2016 at 3:05 pm

Sorry, Mark, it was a bad joke about the unavailability of Universal’s back catalogue. I know the realities are always more complex. :/

Lesley · April 8, 2016 at 11:36 am

Excellent review, Danny.

Here’s my own meditation on this one and Scarlet Empress (Part II of a two-parter, Part I on The Bitter Tea…

http://secondsightcinema.com/strangers-in-a-strange-land-pt-ii-marlene-dietrich-in-josef-von-sternbergs-shanghai-express-1932-and-the-scarlet-empress-1934/

Danny · April 13, 2016 at 3:06 pm

Gonna keep stabbing myself in the leg for missing this. Thanks for sharing Lesley!

Dan in Guadalajara · April 8, 2016 at 12:42 pm

Danny, I love your work. Just a quick note–did you mean Clive Brook instead of Colin Clive, of ‘Frankenstein’ fame?

Danny · April 13, 2016 at 3:06 pm

I’m an idiot. Fixed. Thanks!

erichkuersten · April 8, 2016 at 10:23 pm

On TCM they say that their festival this summer has restored new prints of SHANGHAI EXPRESS and HORSEFEATHERS. The latter is great news as there’s that garbled up scene in Thelma Todd’s apartment which has been a problem since the beginning of its TV screenings. and SHANGHAI has always looked washed out and wan, it feels like it could look a lot better (the way, say, DISHONORED does on that same TCM DVD set). As SHANGHAI is one of my favorite all time movies, needless to say I’m aswoon.

Danny · April 13, 2016 at 3:07 pm

Yeah, I really can’t wait for the new versions– the Paramount Marxes are especially washed out.

Ace · July 5, 2018 at 3:24 am

What is the French officer’s “disgrace”? Ahhhhh, I wanna know. That jump cut about 40 minutes in when he’s being questioned.

Comments are closed.